Ilargi: Another fine article from German magazine Der Spiegel’s English edition.

What makes perfect sense from a short-term economic point of view comes back to devour its own tail, destroying all societies involved in the process. If ever we needed confirmation that our economic models are nothing but dumb failures, belief systems devoid of any and all scientific foundation, designed instead solely to justify shortsighted greed, we now only have to look around our own neighborhoods and our own stores.

When the labels at Wal-Mart start saying Made in Vietnam, we'll know that economic efficiency has once more triumphed. But we no longer will have jobs that allow us to buy much of anything, since there will be no labels left that say Made in America or Made in France.

Globalization's Victors Hunt for the Next Low-Wage Country

What can Western companies do when China's factory workers start demanding better wages and conditions? Easy -- just transfer production to a cheaper country. China's loss is Vietnam's gain.

The world's manufacturing powerhouse needs new low-wage workers, which is why the man in the dark suit is talking himself hoarse. "Do not delay," he calls out to the people gathered around him, pressing his mouth to the microphone. "We will handle everything in minutes, and you'll have work right away."

The man, whose name is Zhou Liang, works for a private employment agency, which has its office in a bus terminal in Shenzhen, the southern Chinese industrial center. Buses are constantly arriving at the terminal from all across China, bringing in fresh supplies of young migrant workers.

But Zhou, the employment agent, sounds desperate, like someone trying to hawk a product no one wants. Posters on the wall advertise some of the lowest-paid jobs in the world. A wide range of factories are seeking workers, but they pay only the minimum monthly wage of 750 yuan, or about €70 ($107), and that for an eight-hour day, five days a week. But by working overtime and on weekends, Zhou calls out, hoping for takers, workers can easily earn twice as much.

He has finally managed to drum up 40 applicants, and he asks them to line up in three rows. One of them is 20-year-old Zhong Xia from Sichuan province. Her luggage consists of a suitcase and a plastic bucket. The bucket is so she can wash her clothes in the factory dormitory where she is likely to be living soon, sharing a room with several other women.

The young woman is given a job assembling electric components, including cables and plugs. It's a start, and better than nothing, she says quickly before her group is led away to a waiting row of minibuses that will take the workers to factories. The entire process is designed to happen as quickly as possible, to deter workers from changing their minds at the last minute. Labor has become a scarce commodity in China these days.

There is a shortage of 2 million workers in the Pearl River Delta alone, China's industrial zone abutting Hong Kong, where companies from Adidas to Mattel have their products manufactured. The manufacturers there compete relentlessly for labor, fighting desperately for each worker. This struggle marks a new chapter in the history of globalization.

For a long time, it seemed as if China, with its 1.3 billion people, offered the world an inexhaustible reservoir of low-wage workers. It was the basis of the recipe for success that reformer Deng Xiaoping prescribed for the country 30 years ago. Foreign companies would outsource the production of simple products to China. And the communists would provide them with the workers they needed.

Everyone benefited from the arrangement. About 300 million Chinese were liberated from deep poverty, and China transformed itself into a principal supplier for the industrialized countries. Consumers in the West were pleased they could buy cheap T-shirts and sneakers.

But now this symbiotic system is no longer working as smoothly as it did in the past. A booming economy in the country's poorer western provinces has caused the influx of migrant workers to subside, as many Chinese prefer to look for work closer to home. This in turn has forced businesses to completely revise their assumptions.

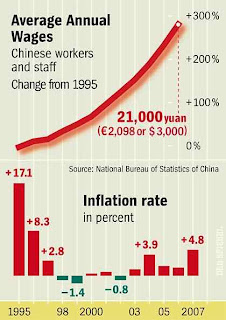

Costs are on the rise everywhere. The labor shortage has made production more expensive, as workers can now command higher wages. A more stringent labor law, more expensive raw materials and the revaluation of the Chinese yuan against the dollar have also contributed to rising costs. Inflation recently climbed to 8 percent. China's role as the ultimate low-cost production location is fast becoming history.

German investors, once lured to the Far East by low costs, have recently begun to realize that the financial advantages of outsourcing production to China have all but vanished. "Turning a profit is becoming increasingly rare," reports consultant Wilfried Krokowski, who specializes in helping German companies enter the Chinese market.

As result, production regions like the Pearl River Delta are experiencing a veritable exodus. According to a survey by the US Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, one in five companies are already considering pulling out of China. Many are taking their factories to places where wages are now lower, like Vietnam, Bangladesh or India.

Or they shut down completely, like the Boji Company. Until recently, Boji was one of the world's largest producers of artificial Christmas trees, employing 20,000 people. Now its complex of buildings in Shenzhen is abandoned and its factory stores closed. "We want our money," angry suppliers have scrawled on the walls.

In December and January alone, more than 1,000 companies left the Pearl River Delta. Most were from Taiwan or neighboring Hong Kong. But they are merely the tip of the iceberg. According to Stanley Lau, the deputy head of a Hong Kong federation of businesses, 10 percent of the up to 70,000 small and mid-sized manufacturers in the area will likely close up shop this year.

About 4,000 companies in the shoe industry, says Lau, have already shut down. What is most surprising about this exodus is that no one in China is concerned about the departure of these sweatshops. There have been no major protests or desperate appeals from politicians. On the contrary, the change is intended.

China's planners know that their country has no future as a low-cost producer. Following in the footsteps of Japan and South Korea, they are converting their industrial base, hoping to catapult Chinese industry to the high-tech level.

It is a change that Beijing's communist strategists are promoting as energetically as only dictatorships can.

Beijing recently eliminated some incentives for foreign investors, including exemptions from corporate income tax and tax discounts for many export goods. As a result, it has become nearly impossible to turn a profit exporting certain products, like shoe leather.

At the same time, Beijing seeks to promote the social "harmony" that Communist Party leader and President Hu Jintao constantly touts. It is a campaign meant to counteract growing dissatisfaction in the People's Republic. Beijing's subjects are becoming aware of their rights and are no longer willing to be exploited.

Every few days, workers at Clever Metal & Electroplating in Shenzhen suddenly stop working. Wearing blue uniforms with yellow numbers attached to them, they squat on the side of the road, looking harmless enough -- almost as if they were having a picnic. But the mood is tense.

The workers say that they have been waiting for their pay for two weeks. They speculate that the company's managers are running out of money, just as they are gradually losing patience. "I spray-paint metal frames for up to 12 hours a day," complains one worker, "and even the thin mask I wear doesn't keep out the stench."

Conditions still haven't improved significantly in many Chinese factories. The employers pay starvation wages, neglect to give credit for overtime hours and ruin the health of their employees. A worker with Taiway, a supplier to the sporting goods industry, describes how rough life is behind the scenes in a Chinese factory.

Using a device only slightly larger than a toothbrush, she spends up to 10 hours a day applying glue to shoe soles. The stench is terrible and she often suffers from headaches. Although the company has distributed face masks, the worker says, they are so ineffective that hardly anyone wears them -- except when the inspectors visit.

Every night, she falls into bed, exhausted. She shares a room with six other women in the company-owned dormitory. There are no showers for the workers, who must carry hot water in buckets to wash themselves.

In the past, the Chinese would have quietly tolerated such conditions. But now they are no longer willing to accept them, and they can even expect support from the very top. The new labor law, introduced at the beginning of the year, provides employees with improved protections against dismissal and higher settlement payments. It also drives up costs for companies, especially low-wage producers.

The Caravan Moves On

Manager Huang Hanxin, 68, is fighting the new wave of costs on all fronts. He heads Sha Wan Dian Ji, one of the world's largest producers of hair dryers, which produces some 7 million units a year. The workers, most of them young women, assemble hair dryers that will be sold under the brand names Revlon, Conair, Babyliss and Vidal Sassoon. They put together the plastic housings at an almost acrobatic rate, with 70 women assembling 3,000 units a day on each assembly line.

The factory once achieved a 15-percent profit, but today that figure has dropped to between 3 and 5 percent, says Huang, adding that the revaluation of the yuan against the dollar has been seriously detrimental to the company. Besides, says Huang, more stringent environmental protection laws have added 3 to 5 percent to the cost of production.

The European Union recently demanded that manufacturers reduce the content of hazardous substances like lead or cadmium in electronic devices. This, says Huang, means buying different and more expensive materials.

The buyers of imported goods from China are finding that their prices have jumped considerably, especially for ordinary items like clothing and shoes. Top purchasing managers from German trading companies and manufacturers confirm that "made in China" is no longer synonymous with "unbeatably cheap."

Sources at German mail-order giant Otto say that they have noticed "significant price hikes," especially for textiles. Kaufhof, a major German department store, has also seen steadily rising prices for Chinese-made products. Company sources say they are "concerned" about the situation. Indeed, the situation is a source of concern for anyone who does business with China, especially small and mid-sized companies.

Chinese suppliers have raised prices across the board, says Mario Moeschler, a marketing executive with Winora, a bicycle manufacturer based in the Bavarian city of Schweinfurt, who says the price hikes vary between 5 and 10 percent. "We have been informed of the price increases," says Moeschler, who receives three or four such letters from China every week.

The explanation for the price increase is always the same, he says: The invoice amount is higher, unfortunately, because steel and aluminum have become so incredibly expensive. Such price hikes are especially detrimental to bicycle manufacturers, who get many of their parts, like frames and forks, from China.

Of course, prices for raw materials have also risen everywhere else in the world. But what is making products from China so much more expensive now is the enormous increase in labor costs. An annual increase of 10 percent and more for wages and salaries has now become the rule.

Nowadays a Chinese engineer earns about €20,000 ($31,000) a year, about twice as much as at the beginning of the decade. In addition, it is growing more and more difficult to find -- and retain -- such qualified workers.

It comes as no surprise that 94 percent of German companies with business relations in China expect wage costs to continue rising, as a survey by the management consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and the Federal Association of Materials Management, Purchasing and Logistics has shown. According to the study, the average price saving with Chinese products is now only about 10 percent. Companies say it is not unusual for them to even take a loss.

"As quality standards rise and the level of automation increases, and as time constraints become more restrictive, sourcing products from China is becoming less and less attractive, from a price standpoint," says PwC expert Klaus Schulten. Importers started looking for alternatives long ago. "Eastern Europe and India," the PwC study concludes, "will become substantially more important as procurement markets in the medium term." It seems that the caravan is moving on.

A Model Employer

And the shoe industry sets the tone. Hundreds of companies have already had to close their factories in China's Guangdong province. In return, hundreds have launched new operations in countries like India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Vietnam and Cambodia. Ironically, the German shoe industry sometimes runs into old acquaintances there: Often it is the Chinese who develop factories in these countries.

Thomas Schneider, 52, has also set up shop in Vietnam, the promised land of the international shoe industry, where most of his customers -- global brands from the Adidas Group to Timberland -- are increasingly having their shoes manufactured. Schneider inquired with countless industrial parks before finding an area near Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon. Beginning in August 2009, 200 workers will be tanning leather for Schneider at the new facility.

Schneider, who learned the tanning business in Reutlingen near Stuttgart, had almost put down roots in China. He developed a leather factory in Taiwan and, in the early 1990s, followed the leather industry to China, the latest low-wage paradise at the time.

Schneider now operates one of China's largest tanneries in Guangdong, where his company, ISA Tan Tec, developed environmentally friendly production systems and provides exemplary occupational health and safety, thereby revolutionizing the notoriously polluted and unsafe tannery industry.

But now his model factory has run into difficulties. Last year, the government in Beijing withdrew tax breaks for export goods like leather. Beginning in April, ISA Tan Tex began paying close to 18 percent of the selling price in duties to supply shoe factories abroad. In the past, the surcharge was only a little over 2 percent.

General price increases -- due to higher wages, a record inflation rate of more than 8 percent and the yuan's rising exchange rate -- have also complicated matters. But the worst thing in China, says Schneider, is uncertainty, because officials in Beijing plan to decide on the level of tax breaks on a year by year basis. This makes it impossible for any company to plan reliably for the future.

Because of high costs, Schneider has already reduced his workforce in Guangdong from 1,000 to 800 workers. Until the planned factory in Vietnam is ready for operation, he is already having leather produced in Vietnam by another manufacturer. After all, his customers are not going to wait for him.

Schneider is also planning his new location near Ho Chi Minh City as a showcase factory. Although he is only required to pay workers in Vietnam just half as much as workers in China -- about €42 ($65) a month -- the shoe companies' strict requirements on environmental protection and safety are just as applicable there. Schneider has no compunctions about complying, because his environmentally friendly production methods are in fact his strongest asset in the fight against his competition.

Schneider even plans to reduce the temperature in his factory by using a heat pump. In addition to lowering CO2 emissions, such techniques also allow Schneider to reduce his electricity costs. Prices are also going up in Vietnam, where inflation is close to 20 percent.

During a fact-finding visit, Schneider heard stories from other bosses about how tough the competition for qualified personnel is. After Tet, the Vietnamese New Year, thousands of Vietnamese didn't return to their jobs -- they switched to companies that pay more.

But Schneider has no choice. The next stage in the game is Vietnam -- at least until his customers in the shoe industry decide it's time to move on to the next low-wage country.

By Alexander Jung and Wieland Wagner

Translated from the German by Christopher Sultan

3 comments:

Total housing starts were up 8.2% since last month, but plummeted 30.6% below the level of construction in April 2007.

I wonder how seasonal that 8.2% is. I also wonder at how they determine a start, is it by unit, or by price, maybe floor area or number of Johns? Confused!

CR, I think you might have meant this to go in today's Debt Rattle thread.

From the graph I posted you can see that year over year March '07 vs '08 was ±1.5 million vs 0.95 million. A worse decline than for April y-o-y.

Most of the rise came from condo's and multifamily units, as a few articles explained.

From yesterday's Debt Rattle:

Construction of U.S. single-family houses in April dropped to the lowest level in 17 years, even as building of condominiums and townhouses rebounded.

Builders broke ground on 692,000 single-family homes at an annual rate, the fewest since January 1991, the Commerce Department said today in Washington.

Total housing starts jumped 8.2 percent to 1.032 million as construction of multifamily units rose 36 percent following a 35 percent drop in March.

"You cannot take the headline starts number seriously because of the increase in the multifamily number," said Ian Shepherdson, chief U.S. economist at High Frequency Economics in Valhalla, New York, who had the closest estimate in a Bloomberg News survey.

"The trends are horrific" because "why would you spend money to buy a depreciating asset?"

"China's planners know that their country has no future as a low-cost producer. Following in the footsteps of Japan and South Korea, they are converting their industrial base, hoping to catapult Chinese industry to the high-tech level."

Makes sense. You don't get to be a superpower by making shoes. You get there by making cars and planes and ships, because that gives you the industrial base for a modern military. And of course you need a PC and robotics industry so you can build advanced weapons.

I'm not suggesting they are expansionist - rather they are reacting to their humiliation by foreign powers during the 19th century, and want to get into a postion where they dictate the terms for a change.

The fact that millions of poor Chinese workers are starting to get a little bargaining power and small improvements in their work conditions is something to be celebrated.

Of course it will force employers to move up the value chain. The most exploitative, lowest paid jobs will move somewhere else, and hopefully the process will be repeated a decade down the track with Vietnamese or Indian workers gradually getting better conditions.

I'd be interested to see if the Chinese start opening up sweatshops in Africa. After that, the the race to the bottom will have nowhere else to go.

In the meantime, I expect China to lurch continually upwards, exporting increased demand for commodities and rising prices for basic goods.

Deflation in the USA affecting global asset pricess, inflation in China affecting global commodity prices, that's what I expect.

With the poor and the disappearing middle class getting crushed between the two forces.

Post a Comment