Post Office, Washington. Flag Day

Ilargi: On this fine holiday, a bunch of numbers to sober you up. Let's stay with real estate. The New York Post reports that $1.4 trillion in commercial real estate debt runs the risk of failing to be re-financed in the next 4 years. But is you think that’s bad, it's just the start. The losses on CRE in that period will be many times that, making re-financing a non-issue.

The New York Times runs a piece on residential real estate developments. Not looking good. Even so, first something that struck me. Here's a quote from the NYT piece:

In the first two months of the year alone, another 313,000 mortgages landed in foreclosure or became delinquent at least 90 days, according to First American CoreLogic.

Followed by this from CBC.ca on May 13:

RealtyTrac, a California-based company that markets real estate, said that banks and other authorities slapped foreclosure actions on more than 340,000 properties in [April]."This would mean foreclosure numbers doubled in April vs Jan/Feb. That would seem steep, even if moratoriums ended, What I suspect is that First American CoreLogic's data are on the conservative side. Something to keep in mind when reading the following:

From November to February, the number of prime mortgages that were delinquent at least 90 days, were in foreclosure or had deteriorated to the point that the lender took possession of the home (REO) increased more than 473,000, exceeding 1.5 million, according to a New York Times analysis of data provided by First American CoreLogic, a real estate research group. Those loans totaled more than $224 billion. During the same period, subprime mortgages in those three categories increased by fewer than 14,000, reaching 1.65 million. The number of similarly troubled Alt-A loans — those given to people with slightly tainted credit — rose 159,000, to 836,000.

So from November to February, default filings on prime mortgages rose some 50%, covering a total of $224 billion in loans.

Over all, more than four million loans worth $717 billion were in the three distressed categories in February (the RealtyTrac website states 1.9 million foreclosures at the end of April), a jump of more than 60 percent in dollar terms compared with a year earlier. Under a program announced in February by the Obama administration, the government is to spend $75 billion on incentives for mortgage servicing companies that reduce payments for troubled homeowners. The Treasury Department says the program will spare as many as four million homeowners from foreclosure. But three months after the program was announced, a Treasury spokeswoman, Jenni Engebretsen, estimated the number of loans that have been modified at "more than 10,000 but fewer than 55,000."

The Obama anti-foreclosure measures are painful failures, that much is clear. A 1.4% success rate in 3 months is dismal and abysmal. Moreover, I estimate that lenders (read: the 4 big US banks) will lose upwards of $300 billion just on the $717 billion that are listed in the 3 distressed categories AT PRESENT. And it doesn't stop there. There's much more to come, numbers are going up fast, and the Option-ARM and Alt-A resets haven't even started for real. There is one factor that drives the issue more than any other as it is going forward:

Last year, foreclosures expanded sharply as the economy shed an average of 256,000 jobs each month. Since then, the job market has deteriorated further, with an average of 665,000 jobs vanishing each month. Each foreclosure costs lenders $50,000, according to data cited in a 2006 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, so an additional two million foreclosures could mean $100 billion in lender losses.

I have to admit, I don't know what the Chicago Fed incorporates in that number, but it can't possibly be ALL losses. More likely, it’s merely the transaction and litigation costs. And that still leaves a dark horse the New York Times doesn't mention: securities portfolio's based on the mortgages involved, and don’t let's get into wider derivatives. Suffice it to say that potential losses per foreclosure are many times more than $50.000. Still, to get back to that one major driving factor, here's the NYT again:

Economy.com expects that 60 percent of the mortgage defaults this year will be set off primarily by unemployment, up from 29 percent last year.

Note: this doesn't mean the factors setting off defaults have improved, just that defaults caused by unemployment have risen enormously, along with job losses.

To sum it up: close to 2 million foreclosures are done. 4 million more mortgages are in "distress", half of which are very likely to be foreclosed on sometime in the next year. And there's still no way on earth the foreclosures can be handled faster than new ones come in. The US loses over 600.000 jobs a month, and talking about green shoots may stall a further increase a few months, but no more than that. If I may repeat an old piece of information: if the US automotive industry cuts production in half, that will 2.5-3 million jobs. At present, the industry runs at 42% of capacity.

And that is with heavy government subsidies of the lending industry, especially GMAC. Take that away, and car sales drop to not to the 10 million Obama talked about this weekend, but more likely below 5 million. And of course, as I keep on saying, the mortgage industry I started this off with would be equally disabled without your money paying for your neighbors' home. Yes, that's right, you're paying for his car too. The chances he'll default on either or both of those loans are higher now than when you started reading this. Are you sure you feel that's a good way to spend your remaining dough?

I’m right, you know, home prices will fall 80% or more peak to trough. if only because you can hardly even afford to pay for your own home and car, let alone you neighbors as well. You don't feel it that way yet because you pay for his in an indirect way. But you do pay.

Job Losses Push Safer Mortgages to Foreclosure

As job losses rise, growing numbers of American homeowners with once solid credit are falling behind on their mortgages, amplifying a wave of foreclosures. In the latest phase of the nation’s real estate disaster, the locus of trouble has shifted from subprime loans — those extended to home buyers with troubled credit — to the far more numerous prime loans issued to those with decent financial histories. With many economists anticipating that the unemployment rate will rise into the double digits from its current 8.9 percent, foreclosures are expected to accelerate.

That could exacerbate bank losses, adding pressure to the financial system and the broader economy. "We’re about to have a big problem," said Morris A. Davis, a real estate expert at the University of Wisconsin. "Foreclosures were bad last year? It’s going to get worse." Economists refer to the current surge of foreclosures as the third wave, distinct from the initial spike when speculators gave up property because of plunging real estate prices, and the secondary shock, when borrowers’ introductory interest rates expired and were reset higher.

"We’re right in the middle of this third wave, and it’s intensifying," said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Economy.com. "That loss of jobs and loss of overtime hours and being forced from a full-time to part-time job is resulting in defaults. They’re coast to coast." Those sliding into foreclosure today are more likely to be modest borrowers whose loans fit their income than the consumers of exotically lenient mortgages that formerly typified the crisis. Economy.com expects that 60 percent of the mortgage defaults this year will be set off primarily by unemployment, up from 29 percent last year.

Robert and Kay Richards live in the center of this trend. In 2006, they took a 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage — a prime loan — borrowing $172,000 to buy a prefabricated house. They erected the building on land they owned in the northern Minnesota town of Babbitt, clearing the terrain of pine trees with their own hands. Mr. Richards worked as a truck driver, hauling timber from a nearby mill. His wife oversaw the books. Together, they brought in about $70,000 a year — enough to make their monthly mortgage payments of $1,300 while raising their two boys, now 11 and 16.

But their truck driving business collapsed last year when the mill closed. Mr. Richards has since worked occasional stints for local trucking companies. His wife has failed to find clerical work. "Every month that goes by, you get a little further behind," Mr. Richards said. Last June, they missed their first payment, and they have since slipped $10,000 into arrears. They are trying to persuade their bank to cut their payments ahead of a foreclosure sale.

From November to February, the number of prime mortgages that were delinquent at least 90 days, were in foreclosure or had deteriorated to the point that the lender took possession of the home increased more than 473,000, exceeding 1.5 million, according to a New York Times analysis of data provided by First American CoreLogic, a real estate research group. Those loans totaled more than $224 billion. During the same period, subprime mortgages in those three categories increased by fewer than 14,000, reaching 1.65 million. The number of similarly troubled Alt-A loans — those given to people with slightly tainted credit — rose 159,000, to 836,000.

Over all, more than four million loans worth $717 billion were in the three distressed categories in February, a jump of more than 60 percent in dollar terms compared with a year earlier. Under a program announced in February by the Obama administration, the government is to spend $75 billion on incentives for mortgage servicing companies that reduce payments for troubled homeowners. The Treasury Department says the program will spare as many as four million homeowners from foreclosure. But three months after the program was announced, a Treasury spokeswoman, Jenni Engebretsen, estimated the number of loans that have been modified at "more than 10,000 but fewer than 55,000."

In the first two months of the year alone, another 313,000 mortgages landed in foreclosure or became delinquent at least 90 days, according to First American CoreLogic. "I don’t think there’s any chance of government measures making more than a small dent," said Alan Ruskin, chief international strategist at RBS Greenwich Capital. Last year, foreclosures expanded sharply as the economy shed an average of 256,000 jobs each month. Since then, the job market has deteriorated further, with an average of 665,000 jobs vanishing each month. Each foreclosure costs lenders $50,000, according to data cited in a 2006 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, so an additional two million foreclosures could mean $100 billion in lender losses.

The government’s recent stress tests of banks concluded that the nation’s 19 largest could be forced to write off as much as a fresh $600 billion by the end of 2010, bringing their total losses to $1 trillion. The Federal Reserve concluded that these banks needed to raise another $75 billion. Many economists pronounce that assessment reasonable, while cautioning that it could become inadequate if foreclosures continue to accelerate. "The margin for error is not that big," said Brian Bethune, chief United States financial economist for HIS Global Insight. "It’s kind of like, ‘Let’s keep our fingers crossed that we’ve seen the worst.’ "

Among prime borrowers, foreclosure rates have been growing fastest in states with particularly high unemployment. In California, for example, the unemployment rate rose to 11.2 percent from 6.4 percent for the year that ended in March, while the foreclosure rate for prime mortgages nearly tripled, reaching 1.81 percent. Even states seemingly removed from the real estate bubble are seeing foreclosures accelerate as the recession grinds on. In Minnesota, three of every five people seeking foreclosure counseling now have a prime loan, according to the nonprofit Minnesota Home Ownership Center.

In Woodbury, Minn., Rick and Christine Sellman are struggling to persuade their bank to reduce their $2,200 monthly mortgage on their five-bedroom home. Mr. Sellman, a construction worker, found some work putting in asphalt driveways last summer, but he is now receiving unemployment. Ms. Sellman’s scrapbooking businesses shut down last summer. Since then, they have slipped $19,000 behind on their mortgage. "We were always up on our house payments," Ms. Sellman said. "You work so hard to keep what you have, and because of circumstances beyond our control now, there’s nothing we can do about it."

S&P’s warning to Britain marks the next stage of this global crisis

"This is the next stage of the global crisis." Simon Johnson, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), is hardly renowned for hyperbole, so his description of the events of the past week, including Standard & Poor's warning over Britain's creditworthiness, is difficult to ignore. Thought we were on the long road to recovery; that economies and financial systems were now back in rude health; that interest rate cuts and quantitative easing were likely to push us out of recession and generate another boom? Not so fast.

When the ministers and central bankers from the world's richest nations met last month in Washington there was little room for back-slapping. Sure, they had seen their economies through the worst of the financial crisis. Most banks had been rescued from full-scale implosion. Governments had taken drastic measures to shore up their capital and ensure their survival. But the mountain of debt that had poisoned the financial system had not disappeared overnight. Instead, it has been shifted from the private sector onto the public sector balance sheet. Britain has taken on hundreds of billions of pounds of bank debt and stands behind potentially trillions of dollars of contingent liabilities.

If the first stage of the crisis was the financial implosion and the second the economic crunch, the third stage – the one heralded by Johnson – is where governments start to topple under the weight of this debt. If 2008 was a year of private sector bankruptcies, 2009 and 2010, it goes, will be the years of government insolvency. That, at least, is the horror story. It was one underlined by S&P's decision to change the outlook on Britain's debt from "stable" to "negative". While the UK still clings on to its prized AAA rating, it now stands a very real chance of losing it within two years – 37pc if past experience is any guide. Questionable as are the credentials of the agencies following the financial crisis, the significance should not be underestimated – particularly not in the case of the UK. A cut in S&P's ratings would reflect a considered opinion that this country may default for the first time in its history.

If Japan's experience in 2001 is anything to go by, it would also trigger an instant exodus of cash from foreign investors, since many of their reserve managers are obliged to invest the vast bulk of their cash in AAA-rated currencies. And all of this is before one even factors in the humiliation such an experience would be likely to inflict on the Government – whatever hue it is by then. But in spite of all this potential fire and brimstone, the reaction from financial markets in the wake of the S&P announcement was hardly dramatic. Gilt prices dipped sharply, but recovered their poise after a few hours. The FTSE 100 fell, but recovered the following day. After dropping precipitously straight after the announcement, the pound bounced back sharply. As the week ended it was knocking on $1.59 – the highest level since last November and hardly a currency in the midst of an obvious crisis.

Moreover, according to Simon Derrick of Bank of New York Mellon, who monitors the actual flow of cash streaming in and out of the economy, there was little evidence from activity on Thursday and Friday to suggest that the S&P decision had suddenly swung investors away from the UK. "Flows into sterling-denominated fixed income have certainly flattened out over the past month," he said. "There is a caution about buying anything sterling-denominated. It's early days, but it hasn't deteriorated much further since Thursday. And the pound still compares very well against dollar and euro-denominated debt. It seems to me that investors aren't looking at the UK in any more negative a light than the US or eurozone."

Indeed, so far as markets were concerned, a couple of disastrous headlines for the Government – the S&P decision and the IMF's verdict on the management of the economy the previous day – were no more a concern than the latest nasty set of economic output or employment data from the Office for National Statistics. Still, capital markets are unpredictable. As emerging markets – which have suffered sudden crises as international investors abandoned ship – know to their cost, creditors can turn on a sixpence. It is a cause for real concern in Whitehall, where officials and politicians are under little delusion about how reliant Britain is on support from the capital markets.

The Government is set to run a major deficit for the next five years at least, as it borrows deep to avoid the recession intensifying and satisfy its spending pledges. Unless the Government can borrow this cash, it will be forced to raise taxes and cut spending at an eye-watering rate. Foreign investors hold around a third of UK debt – most of it in the short-term gilt market. Unlike Japan, which had a massive saving glut when it lost its AAA-rating, the UK is directly vulnerable if their central banks and sovereign wealth funds turn a cold shoulder on sterling. Says one money market insider from a major investment bank: "We were called in by a major foreign central bank only the other week. They were asking probing questions about the stability of British debt and the long-term stability of the UK economy. They are genuinely worried."

But in reality the provenance of the cash is less important than the sheer level of revulsion towards the economy. In the 1970s, when the UK faced its last funding crisis and had to be rescued by the IMF, it was the exodus not of foreign investors but of domestic creditors, who relocated their cash to Switzerland and elsewhere, that caused the real problems. As things stand, the UK is the first of the major G7 economies to have been put on watch during this crisis (Japan is already AA). Were it the only country under real threat of downgrade, it would be easy to make baleful predictions about the impact. However, the economic crisis has touched every nation. The UK is likely to be joined by other countries as the full scale of the downturn becomes apparent and more financial skeletons are pulled from the sub-prime closet.

Indeed, the day after the S&P announcement more attention was on the US, which, according to Bill Gross of bond giant Pimco, is just as likely to lose its AAA rating in the coming years. Indeed, the S&P decision seems in fact to have moved the US Treasury yield even more than it did Britain's gilt yield. Neither is it inconceivable that if the recession remains truly global and intensifies rather than mellows in the coming year, we could find ourselves in a world where there are no AAA-rated sovereigns. According to Julian Jessop of Capital Economics: "If conditions deteriorated to the extent that the US were downgraded, many other countries would presumably be in just as big a mess and any hit on the dollar might be at least partially offset by safe haven buying. Sterling could not rely on the same support. But overall, we suspect that the blow to national pride from a rating downgrade would be much greater than the additional harm caused to the financial markets."

So while we may suspect this is how the next stage of the financial crisis will look, it is harder to grasp which countries, or for that matter which businesses or investments, will benefit and which will suffer. Central banks are likely to invest some of their cash in commodities such as gold and oil; tangible assets will become more desirable – perhaps housing may enjoy another boost. For Governments, survival is based on relative rather than absolute strengths. Countries that provide the most feasible and sensible fiscal plans are likely to thrive as they garner investment and support, while those that churn public money while failing to mend their financial systems are the most likely to suffer.

And it is this final point which is perhaps the silver lining for the UK. The S&P announcement this week represented something of an ultimatum. The statement warned that unless the party that wins the election shows clear and convincing signs of putting the fiscal books back in order, a downgrade will surely follow. Neither Gordon Brown nor David Cameron will like it, but this could be the final stick that beats back their first Budget into order. It means they will be forced either to slash spending or raise taxes in as soon as a year. No one will much enjoy this but if it helps preserve Britain's ratings, and thus ensures the UK can keep financing itself, it will be a pain worth suffering. For in the final stage of this crisis, those countries that recover and start to flourish will be those that face up soonest to the new period of fiscal austerity that must last for the next decade.

Mounting sadness behind the happy headlines

One of the driving forces in economics, according to Robert Shiller of Yale, is the story we tell ourselves. We create happy versions of life in the boom times and sad ones in the bust. It might be said the story is the product of events. But the process is circular. Events drive the story, the story drives our behaviour and our behaviour drives events. Franklin Roosevelt grasped the point when he told the American people in 1933 that the only thing they had to fear was fear itself. So what is the story today? On the face of it, a happy one. Equity markets are flying – most of the time, anyway. Investors are hurling billions of new money at the banks, including the most moribund ones. The world’s fund managers, according to the latest Merrill Lynch survey, are positively bubbling.

Their expectations for global growth and corporate earnings are at a five-year high, having been in the pits at Christmas. That mood is shared by the general public, in the US at any rate. Consider the University of Michigan’s survey of consumer sentiment, which asks people how they see things going over the next five years. The reading hit a low last summer – though not as low as in the two oil shocks of 1973 and 1979, or even the recession of 1990. Since then it has rebounded very nearly to its long-run average. That is striking on two counts. First, at the risk of seeming cynical, there is no reason to suppose the general public’s instincts are less trustworthy here than those of investment professionals. Second, it is the mood and therefore the behaviour of the general public that matters above all.

As Prof Shiller put it in a lecture at the London School of Economics last week, the central question now is whether we just got our confidence back. If so, logic suggests our problems should disappear. Prof Shiller is not sure about that, nor am I. It strikes me the feel-good story could be modified by events, in the usual circular way. Equally important, there are other less cheerful stories running alongside it. On the first point, it is instructive that the US popular mood should have started to revive as long ago as July. For it was not until September that most of the really big stuff happened: the collapse of Lehman Brothers, AIG and Washington Mutual. On the other hand, it was already clear by July that the US government was going to bail out Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. So it seems the public had already judged – correctly, on the showing so far – that the government would go to any lengths to shore up the system.

But there are other things which, though foreseeable in principle, could turn out unexpectedly grievous in practice. It seems clear that unemployment will worsen from here, the only question being by how much. As to house prices, further evidence produced by Prof Shiller – an expert on the subject – reminds us of how far we are in unknown territory. The fall to date is without precedent. But so was the previous rise. In 1990, US house prices were in real terms roughly where they had been a century earlier. Then they almost doubled to the peak. The picture in the UK is uncannily similar. Prof Shiller shows a chart comparing house prices in London and Los Angeles in the boom and bust. They are almost identical, with the grim proviso that UK prices have yet to fall nearly as far. That said, let us turn to some of the other stories around. A central part of Prof Shiller’s thesis, as set out in his recent book Animal Spirits, is that people’s mood and behaviour is affected by certain constants, of which we may focus on two: fairness and corruption.

The issue of fairness, particularly in respect of chief executive pay, is scarcely new. But it is when things go wrong that perceived unfairness makes people angry, and thus has consequences. Two examples. First, in the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission has finally proposed that investors should be allowed to nominate directors. The chief investment officer of Calpers, a leading US institution, commented: "The credit debacle represents a massive failure of oversight." Second, Shell has had its directors’ pay package voted down. The oil company had missed targets that would have triggered bonuses, but proposed to pay them anyway. Add to this the furore over abuse of the expenses system by UK Members of Parliament, and we get the impression of a much angrier and unhappier story than the headlines might suggest. Conceivably, we are past the worst. But it does not quite feel like it.

Why US Debt Rating Poses Such a Big Worry to Investors

Even if a downgrade in US credit is not imminent, the underlying conditions that raised such fears are worrying investors about what the future holds. The move Thursday by Standard & Poor's to cut Britain's credit outlook has raised fears that the US may be next. Should that happen, the news likely wouldn't be good for stocks, while the dollar and Treasury prices would dip and gold probably would benefit as an investment of last resort. While a number of experts, including Moody's, largely dismissed such concerns at least for the short term, market experts were leery of what could happen down the road should the country continue to pursue its current debt policies.

"We are heading down a virtually irreversible road where the overall financial picture of the US is going to look very bad," said Peter Tanous, president and director of Lynx Investment Advisory in Washington, D.C. "Is this something to worry about or dismiss? Clearly, it's something to worry about," says Tanous. "In normal times nobody cares, because we're good for it. This time is different because the numbers are getting scary." The sheer magnitude of the numbers being bandied about is causing some investor fear. "All of this translates into hell of a big financial mess that will indeed affect US credit," Tanous said. "I've been in the business for 40 years and I've never used the world trillion before until recently. Unfortunately, it's trillions of dollars we don't have."

Boatloads of US debt in the hands of foreign governments and the myriad problems that can cause, primarily in the form of higher interest rates down the road, are causing the most concerns. As the US continues to issue Treasury notes, there is concern that China and other large debt holders will demand higher yield, sending interest rates up for borrowers and further hampering a real estate recovery. "At some point the market is going to extract a penalty because you're essentially putting the US government credit on the line in so many areas at such a great cost," said Mike Larson, analyst at Weiss Research in Jupiter, Fla. "You're seeing the ramifications of such short-sighted thinking."

Larson has been warning of a Treasury bubble popping since late 2008 and said the most recent conditions are further signal that US government debt prices are on a precipitous track lower, and yields will move higher. Prices and yields move in opposite directions. China has been relied on to buy debt, but a New York Times report Thursday indicated the nation is becoming more selective in buying Treasurys and is moving towards the lower end of the yield curve, a possibly ominous sign for the long-term state of US financial health. Continuing prospects for government bailouts also are raising concern.

"You have to really start asking yourself whether the cure is worse than the disease," Larson said. "The real danger is this trend accelerates and gets out of control. It's a risk that everybody's sort of keeping in the back of their minds, that we start to see more manifestations of the flat-out repudiation of US assets." Beyond that, there is concern about what the debt will mean to the government's budget and how those bills will be paid by future generations. For investors, the end result is caution that springs from an uncertain world where economic weakness pervades and government budgets crumple under their own weight.

"It's going to make funding more expensive. It almost becomes a death spiral, which might be a little overdramatic, but it presents some problems," says Uri Landesman, head of global growth strategies at ING Investment Management in New York. "They way they're running things now certainly is not geared towards keeping a respectable credit rating." Fears of what will happen to the US credit rating came to the forefront Thursday after Pimco co-CEO Bill Gross said the nation was in danger of going the same route as the UK and losing its credit rating. Pimco runs the world's largest bond fund and Gross has been an influential voice in the shaping of monetary policy here and abroad.

Speaking on CNBC earlier Friday, Gross' counterpart, Mohamed El-Erian, said investors were satisfied that the government had stemmed credit and liquidity problems in the short term but were worried about long-range ramifications. "All of us have to worry about unintended consequences of policy action as well as the intended consequences," El-Erian said. "Every sector is having this tug of war between what it has been doing, what it ought to be doing and what people expect it to be doing." The fragility of investor confidence went on full display Thursday after Gross' comments, when equities, Treasurys and the dollar all sold off while gold went upward.

"When the market starts to disbelieve something, the selling can turn violent," Art Cashin, director of floor operations at UBS, told CNBC. Yet the markets turned around a bit Friday, edging higher as investors sought out positions ahead of the extended Memorial Day weekend. Indeed, investors if nothing else, have been resilient since the rally off the March lows, and even talk of the US losing its vaunted credit rating wasn't enough to spoil the holiday optimism. "The market will go down the day of the week that any of these countries are downgraded," Landesman said. "I don't think this fear is going to prevent a market rally if the economy continues to recover and people think the worst is behind us. It will be a glitch in the road."

Why Are Long-Term Rates Going Up? Because Lenders Think We're Screwed?

The whole world is deflating, but long-term interest rates are moving up. See the chart for the 10-yr Treasury:

10 Year Treasury Rates The world is deleveraging. Debt is being drawn down. Securitization of various types of debt has seriously slowed. Banks are cutting back on lending. Home prices are dropping all over the world. Commercial real estate is rolling over, and banks all over the world are exposed. "Recession turns malls into ghost towns" is the headline in today'sWall Street Journal. Personal savings are rising and retail sales are flat to down. Unemployment is rising. All this should be massively deflationary. Interest rates should be falling or at least not rising. But a funny thing is happening. In the past two months, the yield on the ten-year bond has risen by 1%. It has moved 0.38% or almost "4 big handles" in just two weeks. Look at the chart. What is happening?

Why? Tim Geithner thinks it's because traders are recognizing that the economy's beginning to recover. That's one happy theory. And it's possible (fingers crossed). But here are two less-happy theories:

First, long-term rates are going up because traders are getting nervous about future inflation. This is sensible. Given all the money the world is printing, it is quite likely that we're eventually going to have severe inflation, which will destroy the value of savings and bonds. The question is when that will start. (Japan has been able to postpone it for 15 years and counting).

Second, long-term rates are going up because traders are realizing that the world's big economies will need to issue trillions of dollars of new debt to pay for all their deficit spending...and there's just not enough dumb money in the world. Put differently, where is all this money going to come from?

John Mauldin ran some numbers on this over the weekend. The US is in trouble. Japan's in trouble. Germany's in trouble. The UK's in trouble. Spain is in trouble. European banks are in trouble. All of the aforementioned countries, including the US, will be running deficits of over 10% a year, likely for several years to try to stave off economic collapse. The US deficit alone will eat $1.8 trillion next year, forcing the US to issue $1.8 trillion of new debt. When you go out a few years and add in the other countries, the amount of new money required gets very big very fast. And, again, the big question is...where is that money going to come from?Here's John Mauldin:The world is going to have to fund multiple trillions in debt over the next several years. Pick a number. I think $5 trillion sounds about right. $3 trillion is in the cards for the US alone, if current projections are right. The US trade deficit is now down to under $350 billion a year. The Fed can monetize a trillion [buy debt directly from the Treasury, thus printing new money]. Maybe... US savings are going to go up, but where is the incentive to buy ten-year debt at 3.5%? Four-year debt under 2% doesn't do much for your savings growth. Even with monetization and the Chinese buying our debt with the dollars we send them, that still leaves the bond market about $1.5 trillion short, give or take $100 billion...I think the bond market is looking at the mountain of debt that will have to be somehow sold and wondering where such a colossal sum will come from. Where do you find $10 trillion in the next ten years for US debt? And that is just for US government debt. $5 trillion for new global debt in the next two years? In a deleveraged world? How much will the other countries need? What about money needed for businesses and mortgages and credit cards and so on? If you add $10 trillion to the current $11.3 trillion (including Social Security trust funds, etc.), that totals $21 trillion in 2019. Let's be generous and suggest that interest rates will only be an average of 5%. That would be an interest-rate expense of over $1 trillion. That is 25% of projected revenues and 20% of expected expenses. And that assumes you have nominal growth of over 4% for the next ten years. If growth is less, tax revenues will be less.

Put another way: Interest rates may be going up because the bond market is concluding that the world's biggest borrowers are becoming lousy credits. The only way you can induce lenders to lend to lousy credits (subprime borrowers, for example) is to charge sky-high interest rates with lots of onerous terms. So what may be happening in the bond market is that the "teaser rate" of the past few years is resetting to a usurious rate that will make it fantastically expensive to borrow the money we need.

(This is what some bond market vigilantes have been predicting for years, by the way. They've just been wrong for so long that everyone has stopped listening to them. Maybe now they'll be right). The Obama administration (and the governments of the other big countries mentioned above) is betting that it can turn the economy around in time to start paying off the mortgage before the teaser rate resets. Here's hoping the bet works out.

US bonds sale faces market resistance

The US Treasury is facing an ordeal by fire this week as it tries to sell $100bn (£62bn) of bonds to a deeply sceptical market amid growing fears of a sovereign bond crisis in the Anglo-Saxon world. The interest yield on 10-year US Treasuries – the benchmark price of long-term credit for the global system – jumped 33 basis points last week to 3.45pc week on contagion effects after Standard & Poor's issued a warning on Britain's "AAA" credit rating. The yield has risen over 90 basis points since March when the US Federal Reserve first announced its controversial plan to buy Treasury bonds directly, a move designed to force down the borrowing costs and help stabilise the housing market.

The yield-spike may be nearing the point where it threatens to short-circuit economic recovery. While lower spreads on mortgage rates have kept a lid on home loan costs so far, mortgage rates have nevertheless crept back up to 5pc. The Obama administration needs to raise $2 trillion this year to cover the fiscal stimulus plan and the bank bail-outs. It has to fund $900bn by September. "The dynamic is just getting overwhelming," said RBC Capital Markets. The US Treasury is selling $40bn of two-year notes on Tuesday, $35bn of five-year bonds on Wednesday, and $25bn of seven-year debt on Thursday. While the US has not yet suffered the indignity of a failed auction – unlike Britain and Germany – traders are watching closely to see what share is being purchased by US government itself in pure "monetisation" of the deficit.

Don Kohn, the Fed's vice-chair, said over the weekend that Fed actions would add $1 trillion of stimulus to the US economy over time and had already prevented "fire sales" of assets. "The preliminary evidence suggest that our programme has worked," he said. The US is not alone in facing a deficit crisis. Governments worldwide have to raise some $6 trillion in debt this year, with huge demands in Japan and Europe. Kyle Bass from the US fund Hayman Advisors said the markets were choking on debt. "There isn't enough capital in the world to buy the new sovereign issuance required to finance the giant fiscal deficits that countries are so intent on running. There is simply not enough money out there," he said. "If the US loses control of long rates, they will not be able to arrest asset price declines. If they print too much money, they will debase the dollar and cause stagflation.

"The bottom line is that there is no global 'get out of jail free' card for anyone", he said. The US is acutely vulnerable because it relies heavily on foreign goodwill. China and Japan alone hold 23pc of America's $6,369bn federal debt. Suspicions that Washington is trying to engineer a stealth default by letting the dollar slide could cause patience to snap, even if Asian exporters would themselves suffer if they harmed their chief market. The dollar has fallen 11pc against a basket of currencies since early March. Mutterings of a "dollar crisis" may now constrain the Fed as it tries to shore up the bond market. It has so far bought $116bn of Treasuries as part of its "credit easing" blitz, out of a $300bn pool.

When the Fed first said it was going to buy Treasuries in March the 10-year yield to dropped instantly from 3pc to near 2.5pc, but shock effect has since worn off. Any effort to step up purchases might backfire in the current jittery mood. In the late 1940s the Fed was able to cap the 10-year yield at around 2pc, but that was a different world. The US commanded half global GDP and had a colossal trade surplus. The Fed could carry out its experiment without worrying about foreign dissent. Fed chair Ben Bernanke has long argued that central banks can bring down long-term borrowing rates by purchasing bonds "at essentially no cost". His frequent writings rarely ask whether foreigner investors – from a different cultural universe – will tolerate such conduct.

Mr Bernanke is betting that under a floating currency regime there is no risk of repeating the disaster of October 1931, when the Fed had to raise rates twice to stem foreign gold withdrawals, with catastrophic consequences. This assumption may be tested. It is not clear where the capital will come from to cover global bond issues. Asian central banks and Mid-East oil exporters have cut back on their purchases of US and European bonds as reserve accumulation slows. Russia has slashed its holding by a third to support growth at home. Even Japan's state pension fund has become a net seller of bonds for the first time this year the country's population ages.

Japan's public debt will reach 200pc of GDP next year. Warnings by the Japan's DPJ opposition party that, if elected this autumn, it would not purchase any more US debt unless issued in yen, is a sign that the political mood in Asia is turning hostile to US policy. There is no evidence yet that foreigners are in the process of dumping US Treasuries. Brad Setser from the US Council on Foreign Relations said global central banks added $60bn to their US holdings in the first three weeks of May. This is bitter-sweet for Washington. It suggests that private buyers are pulling out, leaving foreign powers as buyer-of-last resort. We just have to hope that G20 creditors agree to put a clothes peg on their nose and keep buying Western debt until the crisis passes, for the sake of the world.

Debt Destroys Solvency

Every loan officer knows the story begins with debt and income. Debt and income define the financial health of a borrower. Is it any different for a country? If yes, then what do you use to determine the financial health of a country?

One method I suggest is a shaman. Mine uses a divining rod. He stands himself inside a circle of cow chips, and keeps a rabbit’s foot, resting on top of his head, but hidden under a baseball cap. And then he sees everything. I wish I could tell you what his chant is, but his guidance is proprietary.

When the shaman won’t work with me, I go back to basics. Debt and income for a borrower’s home or a country’s economy are perfectly synonymous factors: They are the decisive fact defining financial health or sickness.

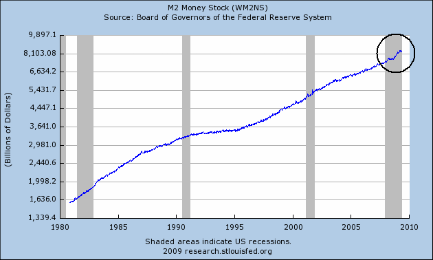

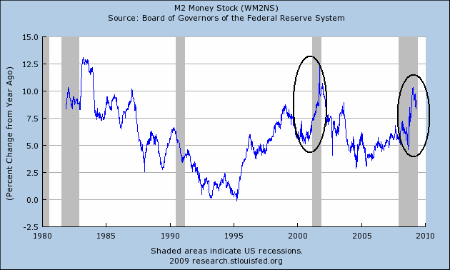

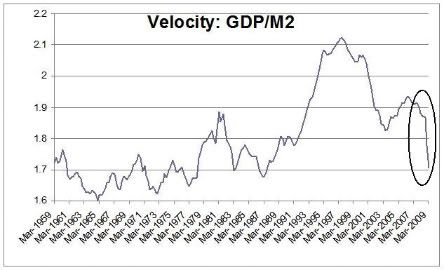

A mortgage lender wants the borrower’s monthly payments, after taking on the new debt, to equal no more than 36% of income. Less is better. More sometimes works. So how do you determine a country’s income? That’s very simple. Substitute gross domestic product (GDP) for income. Then review the chart immediately below.

If, after reviewing the chart, you aren’t crying now, then you don’t know what you have just seen. What does the chart say? It predicts we have unpayable debt equal to $21 trillion. Where all the lines go up in the chart, assume they all have to come back down again. If we write off $21 trillion, the job gets done.

If you play your cards right, it’s enough money to buy every residential property in the United States. And after you buy all those homes you can put a serious killer deck on each and every one of your new property investments. And then, as a closing present, you easily pay for every family in the United States to travel all around the world for 80 days – at least. Tell them to eat and drink whatever they want. If you like to buy wars, wait it out six or 12 months, and buy the property then. You can do it all. It’s crazy what you can do with $21 trillion. Know what I mean?

Before signing off, I should mention a gaping hole in the preceding argument. I have assumed that 1980 was a year of sanity for debt. And I have assumed 2008 was the denouement of decades of debt insanity. Nobody, to my knowledge, has published a detailed report defining the correct ratio of debt-to-GDP/income for a country. I have seen a few mentions here and there, and a few graphs, but nothing convincing or serious.

And if nobody has done that work, what does it mean? It quite simply means that we are all dumb and we don’t know what we are talking about. Now that I’ve said it, doesn’t that sound like the world we all know? I’ve been there anyway.

We can and should confirm that economics is a dismal science. And the herd, including you and me, really should think about going back to school. That’s it for now. Enjoy the bull market. Isn’t it fun to be confident again? Enjoy your holiday weekend. And, if you don’t mind, please pass the Cool Aid. I’ll take a pitcher if you don’t mind? I love that stuff.

We cannot inflate our way out of this crisis

by Wolfgang Münchau

"The first panacea for a mismanaged nation is inflation of the currency; the second is war. Both bring a temporary prosperity; both bring a permanent ruin. But both are the refuge of political and economic opportunists."

Ernest Hemingway, "Notes on the Next War: A Serious Topical Letter" , 1935

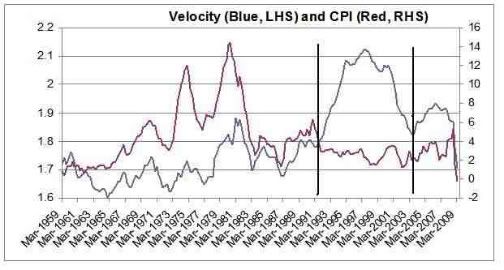

What I hear more and more, both from bankers and from economists, is that the only way to end our financial crisis is through inflation. Their argument is that high inflation would reduce the real level of debt, allowing indebted households and banks to deleverage faster and with less pain. To achieve the desired increase in inflation, the US Federal Reserve should either announce an inflation target or simply keep interest rates at zero when the recovery begins. That way, real interest rates would become strongly negative. The advocates of such a strategy are not marginal and cranky academics. They include some of the most influential US economists.

Four immediate questions arise from these considerations. Can it be done? Can it be undone? Can it be done at a reasonable economic cost? Last, should it be done? Of course, it can be done, but only for as long as the commitment to higher inflation is credible. Inflation is not some lightbulb that a central bank can switch on and off. It works through expectations. If the Fed were to impose a long-term inflation target of, say, 6 per cent, then I am sure it would achieve that target eventually. People and markets might not find the new target credible at first but if the central bank were consistent, expectations would eventually adjust. In the end, workers would demand wage increases of at least 6 per cent each year and companies would strive to raise their prices by that amount.

If, however, a central bank were to pre-announce that it was targeting 6 per cent inflation in 2010 and 2011, and 2 per cent thereafter, the plan would probably not succeed. We know that monetary policy affects inflation with long and variable lags. Such a degree of fine-tuning does not work in practice. My own guess is that one would have to make a much longer-term commitment to a higher rate of inflation for such a policy shift to be credible. I suspect that the greater the distance between the new rate and the current rate, the longer the commitment would have to be.

Could it be reversed, once it had been achieved? Again, the answer is yes; again, the commitment would have to be credible. But herein lies precisely the problem. If the central bank were honest from the start and pre-announced that it would eventually reverse its policy, it might never reach its goal of higher inflation in the first place. If the central bank were dishonest, it might achieve the goal. But it would lose credibility the moment it decided to reverse. So any new credibility would have to be earned through new policy action. This might imply nominal interest rates significantly above 6 per cent for an uncomfortably long period.

What would happen then? I can think of two scenarios. The best outcome would be a simple double-dip recession. A two-year period of moderately high inflation might reduce the real value of debt by some 10 per cent. But there is also a downside. The benefit would be reduced, or possibly eliminated, by higher interest rates payable on loans, higher default rates and a further increase in bad debts. I would be very surprised if the balance of those factors were positive. In any case, this is not the most likely scenario. A policy to raise inflation could, if successful, trigger serious problems in the bond markets. Inflation is a transfer of wealth from creditors to debtors – essentially from China to the US. A rise in US inflation could easily lead to a pull-out of global investors from US bond markets. This would almost certainly trigger a crash in the dollar's real effective exchange rate, which in turn would add further inflationary pressure.

Under such a scenario, it might not be easy to keep inflation close to a hypothetical 6 per cent target. The result could be a vicious circle in which an overshooting inflation rate puts further pressure on the bond markets and the exchange rate. The outcome would be even worse than in the previous example. The central bank would eventually have to raise nominal rates aggressively to bring back stability. It would end up with the very opposite of what the advocates of a high inflation policy hope for. Real interest rates would not be significantly negative, but extremely positive.

Should this be done? A credible inflation target of 2 or 3 per cent, maintained over a credibly long period of time, is useful. But I doubt that a 6 per cent inflation target could be simultaneously credible and sustainable. Tempting as it may be, it is a beggar-thy-neighbour policy unless replicated elsewhere and would come to be regarded as such by many countries in the world. It would produce a whole new group of losers, both inside and outside the US, with all its undesirable political, social, economic and financial implications. It would also fuel the already rampant discussions about the inevitable death of fiat money. Stimulating inflation is another dirty, quick-fix strategy, like so many of the bank rescue packages currently in operation. As Hemingway said, it would feel good for a time. But it would solve no problems and create new ones.

Don't Monetize the Debt

From his perch high atop the palatial Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, overlooking what he calls "the most modern, efficient city in America," Richard Fisher says he is always on the lookout for rising prices. But that's not what's worrying the bank's president right now. His bigger concern these days would seem to be what he calls "the perception of risk" that has been created by the Fed's purchases of Treasury bonds, mortgage-backed securities and Fannie Mae paper. Mr. Fisher acknowledges that events in the financial markets last year required some unusual Fed action in the commercial lending market. But he says the longer-term debt, particularly the Treasurys, is making investors nervous. The looming challenge, he says, is to reassure markets that the Fed is not going to be "the handmaiden" to fiscal profligacy.

"I think the trick here is to assist the functioning of the private markets without signaling in any way, shape or form that the Federal Reserve will be party to monetizing fiscal largess, deficits or the stimulus program." The very fact that a Fed regional bank president has to raise this issue is not very comforting. It conjures up images of Argentina. And as Mr. Fisher explains, he's not the only one worrying about it. He has just returned from a trip to China, where "senior officials of the Chinese government grill[ed] me about whether or not we are going to monetize the actions of our legislature." He adds, "I must have been asked about that a hundred times in China." A native of Los Angeles who grew up in Mexico, Mr. Fisher was educated at Harvard, Oxford and Stanford. He spent his earliest days in government at Jimmy Carter's Treasury. He says that taught him a life-long lesson about inflation.

It was "inflation that destroyed that presidency," he says. He adds that he learned a lot from then Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, who had to "break [inflation's] back." Mr. Fisher has led the Dallas Fed since 2005 and has developed a reputation as the Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) lead inflation worrywart. In September he told a New York audience that "rates held too low, for too long during the previous Fed regime were an accomplice to [the] reckless behavior" that brought about the economic troubles we are now living through. He also warned that the Treasury's $700 billion plan to buy toxic assets from financial institutions would be "one more straw on the back of the frightfully encumbered camel that is the federal government ledger."

In a speech at the Kennedy School of Government in February, he wrung his hands about "the very deep hole [our political leaders] have dug in incurring unfunded liabilities of retirement and health-care obligations" that "we at the Dallas Fed believe total over $99 trillion." In March, he is believed to have vociferously objected in closed-door FOMC meetings to the proposal to buy U.S. Treasury bonds. So with long-term Treasury yields moving up sharply despite Fed intentions to bring down mortgage rates, I've flown to Dallas to see what he's thinking now. Regarding what caused the credit bubble, he repeats his assertion about the Fed's role: "It is human instinct when rates are low and the yield curve is flat to reach for greater risk and enhanced yield and returns." (Later, he adds that this is not to cast aspersions on former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan and reminds me that these decisions are made by the FOMC.)

"The second thing is that the regulators didn't do their job, including the Federal Reserve." To this he adds what he calls unusual circumstances, including "the fruits and tailwinds of globalization, billions of people added to the labor supply, new factories and productivity coming from places it had never come from before." And finally, he says, there was the 'mathematization' of risk." Institutions were "building risk models" and relying heavily on "quant jocks" when "in the end there can be no substitute for good judgment." What about another group of alleged culprits: the government-anointed rating agencies? Mr. Fisher doesn't mince words. "I served on corporate boards. The way rating agencies worked is that they were paid by the people they rated. I saw that from the inside." He says he also saw this "inherent conflict of interest" as a fund manager.

"I never paid attention to the rating agencies. If you relied on them you got . . . you know," he says, sparing me the gory details. "You did your own analysis. What is clear is that rating agencies always change something after it is obvious to everyone else. That's why we never relied on them." That's a bit disconcerting since the Fed still uses these same agencies in managing its own portfolio. I wonder whether the same bubble-producing Fed errors aren't being repeated now as Washington scrambles to avoid a sustained economic downturn. He surprises me by siding with the deflation hawks. "I don't think that's the risk right now." Why? One factor influencing his view is the Dallas Fed's "trim mean calculation," which looks at price changes of more than 180 items and excludes the extremes. Dallas researchers have found that "the price increases are less and less. Ex-energy, ex-food, ex-tobacco you've got some mild deflation here and no inflation in the [broader] headline index."

Mr. Fisher says he also has a group of about 50 CEOs around the U.S. and the world that he calls on, all off the record, before almost every FOMC meeting. "I don't impart any information, I just listen carefully to what they are seeing through their own eyes. And that gives me a sense of what's happening on the ground, you might say on Main Street as opposed to Wall Street." It's good to know that a guy so obsessed with price stability doesn't see inflation on the horizon. But inflation and bubble trouble almost always get going before they are recognized. Moreover, the Fed has to pay attention to the 1978 Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act -- a.k.a. Humphrey-Hawkins -- and employment is a lagging indicator of economic activity. This could create a Fed bias in favor of inflating. So I push him again.

"I want to make sure that your readers understand that I don't know a single person on the FOMC who is rooting for inflation or who is tolerant of inflation." The committee knows very well, he assures me, that "you cannot have sustainable employment growth without price stability. And by price stability I mean that we cannot tolerate deflation or the ravages of inflation." Mr. Fisher defends the Fed's actions that were designed to "stabilize the financial system as it literally fell apart and prevent the economy from imploding." Yet he admits that there is unfinished work. Policy makers have to be "always mindful that whatever you put in, you are going to have to take out at some point. And also be mindful that there are these perceptions [about the possibility of monetizing the debt], which is why I have been sensitive about the issue of purchasing Treasurys."

He returns to events on his recent trip to Asia, which besides China included stops in Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore and Korea. "I wasn't asked once about mortgage-backed securities. But I was asked at every single meeting about our purchase of Treasurys. That seemed to be the principal preoccupation of those that were invested with their surpluses mostly in the United States. That seems to be the issue people are most worried about." As I listen I am reminded that it's not just the Asians who have expressed concern. In his Kennedy School speech, Mr. Fisher himself fretted about the U.S. fiscal picture. He acknowledges that he has raised the issue "ad nauseam" and doesn't apologize. "Throughout history," he says, "what the political class has done is they have turned to the central bank to print their way out of an unfunded liability. We can't let that happen. That's when you open the floodgates. So I hope and I pray that our political leaders will just have to take this bull by the horns at some point. You can't run away from it."

Voices like Mr. Fisher's can be a problem for the politicians, which may be why recently there have been rumblings in Washington about revoking the automatic FOMC membership that comes with being a regional bank president. Does Mr. Fisher have any thoughts about that? This is nothing new, he points out, briefly reviewing the history of the political struggle over monetary policy in the U.S. "The reason why the banks were put in the mix by [President Woodrow] Wilson in 1913, the reason it was structured the way it was structured, was so that you could offset the political power of Washington and the money center in New York with the regional banks. They represented Main Street. "Now we have this great populist fervor and the banks are arguing for Main Street, largely. I have heard these arguments before and studied the history. I am not losing a lot of sleep over it," he says with a defiant Texas twang that I had not previously detected. "I don't think that it'd be the best signal to send to the market right now that you want to totally politicize the process."

Speaking of which, Texas bankers don't have much good to say about the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), according to Mr. Fisher. "Its been complicated by the politics because you have a special investigator, special prosecutor, and all I can tell you is that in my district here most of the people who wanted in on the TARP no longer want in on the TARP." At heart, Mr. Fisher says he is an advocate for letting markets clear on their own. "You know that I am a big believer in Schumpeter's creative destruction," he says referring to the term coined by the late Austrian economist. "The destructive part is always painful, politically messy, it hurts like hell but you hopefully will allow the adjustments to be made so that the creative part can take place." Texas went through that process in the 1980s, he says, and came back stronger.

This is doubtless why, with Washington taking on a larger role in the American economy every day, the worries linger. On the wall behind his desk is a 1907 gouache painting by Antonio De Simone of the American steam sailing vessel Varuna plowing through stormy seas. Just like most everything else on the walls, bookshelves and table tops around his office -- and even the dollar-sign cuff links he wears to work -- it represents something. He says that he has had this painting behind his desk for the past 30 years as a reminder of the importance of purpose and duty in rough seas. "The ship," he explains, "has to maintain its integrity." What is more, "no mathematical model can steer you through the kind of seas in that picture there. In the end someone has the wheel." He adds: "On monetary policy it's the Federal Reserve."

China warns Federal Reserve over 'printing money'

China has warned a top member of the US Federal Reserve that it is increasingly disturbed by the Fed's direct purchase of US Treasury bonds. Richard Fisher, president of the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, said: "Senior officials of the Chinese government grilled me about whether or not we are going to monetise the actions of our legislature." "I must have been asked about that a hundred times in China. I was asked at every single meeting about our purchases of Treasuries. That seemed to be the principal preoccupation of those that were invested with their surpluses mostly in the United States," he told the Wall Street Journal.

His recent trip to the Far East appears to have been a stark reminder that Asia's "Confucian" culture of right action does not look kindly on the insouciant policy of printing money by Anglo-Saxons. Mr Fisher, the Fed's leading hawk, was a fierce opponent of the original decision to buy Treasury debt, fearing that it would lead to a blurring of the line between fiscal and monetary policy – and could all too easily degenerate into Argentine-style financing of uncontrolled spending. However, he agreed that the Fed was forced to take emergency action after the financial system "literally fell apart". Nor, he added was there much risk of inflation taking off yet. The Dallas Fed uses a "trim mean" method based on 180 prices that excludes extreme moves and is widely admired for accuracy.

"You've got some mild deflation here," he said. The Oxford-educated Mr Fisher, an outspoken free-marketer and believer in the Schumpeterian process of "creative destruction", has been running a fervent campaign to alert Americans to the "very big hole" in unfunded pension and health-care liabilities built up by a careless political class over the years. "We at the Dallas Fed believe the total is over $99 trillion," he said in February. "This situation is of your own creation. When you berate your representatives or senators or presidents for the mess we are in, you are really berating yourself. You elect them," he said. His warning comes amid growing fears that America could lose its AAA sovereign rating.

China stuck in ‘dollar trap’

China’s official foreign exchange manager is still buying record amounts of US government bonds, in spite of Beijing’s increasingly vocal fear of a dollar collapse, according to officials and analysts. Senior Chinese officials, including Wen Jiabao, the premier, have repeatedly signalled concern that US policies could lead to a collapse in the dollar and global inflation. But Chinese and western officials in Beijing said China was caught in a "dollar trap" and has little choice but to keep pouring the bulk of its growing reserves into the US Treasury, which remains the only market big enough and liquid enough to support its huge purchases.

In March alone, China’s direct holdings of US Treasury securities rose $23.7bn to reach a new record of $768bn, according to preliminary US data, allowing China to retain its title as the biggest creditor of the US government. "Because of the sheer size of its reserves Safe [China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange] will immediately disrupt any other market it tries to shift into in a big way and could also collapse the value of its existing reserves if it sold too many dollars," said a western official, who spoke on condition of anonymity. The composition of China’s reserves is a state secret but dollar assets are estimated to comprise as much as 70 per cent of the $1,953bn total and China owns nearly a quarter of the US debt held by foreigners, according to US Treasury data.

The collapse of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the US mortgage financiers, last summer prompted Safe to adjust its strategy and start buying far more short-term US government securities, instead of longer-maturity bonds and notes. This approach is widespread in the market because of expectations that the US will have to raise interest rates in the medium term to deal with rising inflation, as a result of all the money that it is printing. But Safe has not fundamentally changed its strategy of allocating the bulk of its burgeoning foreign exchange reserves to US Treasury securities, a western adviser familiar with Safe thinking told the Financial Times.

He said Safe traders were "very negative" on sterling because of expectations of renewed weakness of the UK currency but Safe was neutral on the euro and bullish on the Australian dollar. The pound ended last week at its strongest since December, shrugging off a warning over the UK’s soaring public debt from Standard & Poor’s, a rating agency. The US dollar fell to its lowest level of the year against major currencies last week. Treasury yields spiked to six-month highs as investors focused on the willingness of creditors to fund a deficit that was expected to be about 13 per cent of gross domestic product this year.

China’s determination to keep buying US government debt is helping Washington fund its soaring budget deficit and there is no indication that Beijing will shy away from continued purchases, the Obama administration’s budget chief told a congressional sub-committee last week. As its reserves soared in recent years, Safe began trying to diversify away from the dollar, It has been adding to its gold stocks and taking small equity stakes in publicly listed companies all over the world.

Over the long term, Beijing hopes to reduce the size of its enormous reserves and cut exposure to US Treasury bonds by encouraging state-owned enterprises to use foreign exchange to acquire competitors abroad. Chinese outbound foreign direct investment nearly doubled from 2007 to $52.2bn last year. Beijing announced a plan last week to ease restrictions on domestic companies to make it easier to buy and borrow foreign exchange for offshore investment.

The Weimar Hyperinflation: Time to get out the wheelbarrows?

by Ellen Brown

"It was horrible. Horrible! Like lightning it struck. No one was prepared. The shelves in the grocery stores were empty.You could buy nothing with your paper money."

– Harvard University law professor Friedrich Kessler on on the Weimar Republic hyperinflation (1993 interview)

Some worried commentators are predicting a massive hyperinflation of the sort suffered by Weimar Germany in 1923, when a wheelbarrow full of paper money could barely buy a loaf of bread. An April 29 editorial in the San Francisco Examiner warned: "With an unprecedented deficit that's approaching $2 trillion, [the President's 2010] budget proposal is a surefire prescription for hyperinflation. So every senator and representative who votes for this monster $3.6 trillion budget will be endorsing a spending spree that could very well turn America into the next Weimar Republic."1

In an investment newsletter called Money Morning on April 9, Martin Hutchinson pointed to disturbing parallels between current government monetary policy and Weimar Germany's, when 50% of government spending was being funded by seigniorage – merely printing money.2 However, there is something puzzling in his data. He indicates that the British government is already funding more of its budget by seigniorage than Weimar Germany did at the height of its massive hyperinflation; yet the pound is still holding its own, under circumstances said to have caused the complete destruction of the German mark. Something else must have been responsible for the mark's collapse besides mere money-printing to meet the government's budget, but what? And are we threatened by the same risk today? Let's take a closer look at the data.

In his well-researched article, Hutchinson notes that Weimar Germany had been suffering from inflation ever since World War I; but it was in the two year period between 1921 and 1923 that the true "Weimar hyperinflation" occurred. By the time it had ended in November 1923, the mark was worth only one-trillionth of what it had been worth back in 1914. Hutchinson goes on: "The current policy mix reflects those of Germany during the period between 1919 and 1923. The Weimar government was unwilling to raise taxes to fund post-war reconstruction and war-reparations payments, and so it ran large budget deficits. It kept interest rates far below inflation, expanding money supply rapidly and raising 50% of government spending through seigniorage (printing money and living off the profits from issuing it). . . .

"The really chilling parallel is that the United States, Britain and Japan have now taken to funding their budget deficits through seigniorage. In the United States, the Fed is buying $300 billion worth of U.S. Treasury bonds (T-bonds) over a six-month period, a rate of $600 billion per annum, 15% of federal spending of $4 trillion. In Britain, the Bank of England (BOE) is buying 75 billion pounds of gilts [the British equivalent of U.S. Treasury bonds] over three months. That's 300 billion pounds per annum, 65% of British government spending of 454 billion pounds. Thus, while the United States is approaching Weimar German policy (50% of spending) quite rapidly, Britain has already overtaken it!"

And that is where the data gets confusing. If Britain is already meeting a larger percentage of its budget deficit by seigniorage than Germany did at the height of its hyperinflation, why is the pound now worth about as much on foreign exchange markets as it was nine years ago, under circumstances said to have driven the mark to a trillionth of its former value in the same period, and most of this in only two years? Meanwhile, the U.S. dollar has actually gotten stronger relative to other currencies since the policy was begun last year of massive "quantitative easing" (today's euphemism for seigniorage).3 Central banks rather than governments are now doing the printing, but the effect on the money supply should be the same as in the government money-printing schemes of old.

The government debt bought by the central banks is never actually paid off but is just rolled over from year to year; and once the new money is in the money supply, it stays there, diluting the value of the currency. So why haven't our currencies already collapsed to a trillionth of their former value, as happened in Weimar Germany? Indeed, if it were a simple question of supply and demand, a government would have to print a trillion times its earlier money supply to drop its currency by a factor of a trillion; and even the German government isn't charged with having done that. Something else must have been going on in the Weimar Republic, but what?

Light is thrown on this mystery by the later writings of Hjalmar Schacht, the currency commissioner for the Weimar Republic. The facts are explored at length in The Lost Science of Money by Stephen Zarlenga, who writes that in Schacht's 1967 book The Magic of Money, he "let the cat out of the bag, writing in German, with some truly remarkable admissions that shatter the 'accepted wisdom' the financial community has promulgated on the German hyperinflation." What actually drove the wartime inflation into hyperinflation, said Schacht, was speculation by foreign investors, who would bet on the mark's decreasing value by selling it short.

Short selling is a technique used by investors to try to profit from an asset's falling price. It involves borrowing the asset and selling it, with the understanding that the asset must later be bought back and returned to the original owner. The speculator is gambling that the price will have dropped in the meantime and he can pocket the difference. Short selling of the German mark was made possible because private banks made massive amounts of currency available for borrowing, marks that were created on demand and lent to investors, returning a profitable interest to the banks. At first, the speculation was fed by the Reichsbank (the German central bank), which had recently been privatized. But when the Reichsbank could no longer keep up with the voracious demand for marks, other private banks were allowed to create them out of nothing and lend them at interest as well.4

If Schacht is to be believed, not only did the government not cause the hyperinflation but it was the government that got the situation under control. The Reichsbank was put under strict regulation, and prompt corrective measures were taken to eliminate foreign speculation by eliminating easy access to loans of bank-created money. More interesting is a little-known sequel to this tale. What allowed Germany to get back on its feet in the 1930s was the very thing today's commentators are blaming for bringing it down in the 1920s – money issued by seigniorage by the government. Economist Henry C. K. Liu calls this form of financing "sovereign credit." He writes of Germany's remarkable transformation:

"The Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, at a time when its economy was in total collapse, with ruinous war-reparation obligations and zero prospects for foreign investment or credit. Yet through an independent monetary policy of sovereign credit and a full-employment public-works program, the Third Reich was able to turn a bankrupt Germany, stripped of overseas colonies it could exploit, into the strongest economy in Europe within four years, even before armament spending began."5

While Hitler clearly deserves the opprobrium heaped on him for his later atrocities, he was enormously popular with his own people, at least for a time. This was evidently because he rescued Germany from the throes of a worldwide depression – and he did it through a plan of public works paid for with currency generated by the government itself. Projects were first earmarked for funding, including flood control, repair of public buildings and private residences, and construction of new buildings, roads, bridges, canals, and port facilities. The projected cost of the various programs was fixed at one billion units of the national currency. One billion non-inflationary bills of exchange called Labor Treasury Certificates were then issued against this cost.

Millions of people were put to work on these projects, and the workers were paid with the Treasury Certificates. The workers then spent the certificates on goods and services, creating more jobs for more people. These certificates were not actually debt-free but were issued as bonds, and the government paid interest on them to the bearers. But the certificates circulated as money and were renewable indefinitely, making them a de facto currency; and they avoided the need to borrow from international lenders or to pay off international debts.6 The Treasury Certificates did not trade on foreign currency markets, so they were beyond the reach of the currency speculators. They could not be sold short because there was no one to sell them to, so they retained their value.

Within two years, Germany's unemployment problem had been solved and the country was back on its feet. It had a solid, stable currency, and no inflation, at a time when millions of people in the United States and other Western countries were still out of work and living on welfare. Germany even managed to restore foreign trade, although it was denied foreign credit and was faced with an economic boycott abroad. It did this by using a barter system: equipment and commodities were exchanged directly with other countries, circumventing the international banks. This system of direct exchange occurred without debt and without trade deficits. Although Germany's economic experiment was short-lived, it left some lasting monuments to its success, including the famous Autobahn, the world's first extensive superhighway.7

Germany's scheme for escaping its crippling debt and reinvigorating a moribund economy was clever, but it was not actually original with the Germans. The notion that a government could fund itself by printing and delivering paper receipts for goods and services received was first devised by the American colonists. Benjamin Franklin credited the remarkable growth and abundance in the colonies, at a time when English workers were suffering the impoverished conditions of the Industrial Revolution, to the colonists' unique system of government-issued money. In the nineteenth century, Senator Henry Clay called this the "American system," distinguishing it from the "British system" of privately-issued paper banknotes. After the American Revolution, the American system was replaced in the U.S. with banker-created money; but government-issued money was revived during the Civil War, when Abraham Lincoln funded his government with U.S. Notes or "Greenbacks" issued by the Treasury.

The dramatic difference in the results of Germany's two money-printing experiments was a direct result of the uses to which the money was put. Price inflation results when "demand" (money) increases more than "supply" (goods and services), driving prices up; and in the experiment of the 1930s, new money was created for the purpose of funding productivity, so supply and demand increased together and prices remained stable. Hitler said, "For every mark issued, we required the equivalent of a mark's worth of work done, or goods produced." In the hyperinflationary disaster of 1923, on the other hand, money was printed merely to pay off speculators, causing demand to shoot up while supply remained fixed. The result was not just inflation but hyperinflation, since the speculation went wild, triggering rampant tulip-bubble-style mania and panic.