"Guests of trailer park enjoying the sun and sea breeze at the beach, Sarasota, Florida"

Ilargi: Today we have a guest contribution from one of our regular commenters, El Gallinazo, who weighs in on the dead horse of inflation vs. deflation, dissecting a John Williams Shadowstats paper. And while Stoneleigh and I here at The Automatic Earth haven't had any doubts on the issue in "like forever", keeping the discussion alive in some form may be useful, if only simply since it won't go away.

Just let me state two issues that are obvious to us before handing you over to the cantankerous vulture:

- There is no way we'll get into hyperinflation BEFORE debt deflation has run its course.

- There is no way the Federal Reserve (or ECB, Bank of Japan) can print enough money, electronically or physically, to fabricate hyperinflation, as long as the debt deflation train hasn't finished running over our economic systems.

- After that train is done, it's anybody's guess; the damage done will be so severe there may not be a Fed left to inflate even a party balloon.

El Gallinazo: Beating the Dead Horse (again)

Everyone with three functional synapses and an opposable thumb knows that we are headed into a second great depression. Optimizing survival strategies for anyone lucky enough to have any assets really boils down to the question of deflation versus hyperinflation, or a sequential mixture of the two. Most of the hyperinflationistas are morons, even the ones that don't have a faux Nobel. So it was a pleasure when a commenter at The Automatic Earth tipped me off to John Williams' -relatively- recent paper:

Hyperinflation Special Report (Update 2010)

Even my cantankerous self wouldn't dare to call Williams a moron. So here we have three hyper-intelligent people with three different viewpoints on the subject.

- Robert Prechter: Depression with giant deflation. Cash is king. Inflation nowhere in sight.

- Stoneleigh (as well as Ilargi) at The Automatic Earth: Same as Prechter but with the caveat that when nearly all credit disappears and globalized markets cease, then hyperinflation is likely to kick in. As to a timeline of transition from deflation to hyperinflation, Stoneleigh recently indicated 2 to 5 years.

- John Williams : Like the two above, he also predicts a great depression with deflation as the immediate outcome. However, Williams differs in that he claims that the deflation will be very short lived, a matter of months, and will morph quickly into hyperinflation.

A possible answer to this quandary can be approached by posing the two following questions:

- Would the Fed ever want hyperinflation?

- If so, is the Fed capable of instituting it?

Well, the vote breaks down as the following (as far as I can figure):

Both 1) & 2): Prechter and Stoneleigh - no; Williams - yes.

Prechter is quite clear that the Fed would never want hyperinflation and even if it did, it is quite incapable of pulling it off. Stoneleigh has not really weighed in on whether the Fed would ever want hyperinflation, but she is quite clear that until deleveraging is complete, that the Fed is incapable of instituting it. By that time, the Fed may not exist at all and would certainly be quite different than it is today. Williams has claimed that the Fed has wanted inflation since its inception in 1913, and is quite capable of pulling it off.

Well, I am going to weigh in with some opinions now. Williams defines hyperinflation far more severely than I would. He defines it as inflation that is so severe that the money is worth less than the fabric which it is printed on in a matter of months, and people use it as kindling and rather unhygienic bathroom tissue. In this regard, I would imagine uncirculated bills might fetch a certain premium due to their cleanliness.

Williams claims that hyperinflation is the only way out of the debt trap other than default on treasuries and unfunded obligations. It never seems to occur to Williams that since most unfunded obligations, such as Social Security and Medicare / Medicaid are owed to the helpless and the pissants, as long as NORTHCOM can prevent said pissants from stringing them up to the nearest lamppost, the oligarchs would have little remorse on reneging on these unfunded obligations.

Williams claims that hyperinflation is the only way out of the debt trap other than default on treasuries and unfunded obligations. It never seems to occur to Williams that since most unfunded obligations, such as Social Security and Medicare / Medicaid are owed to the helpless and the pissants, as long as NORTHCOM can prevent said pissants from stringing them up to the nearest lamppost, the oligarchs would have little remorse on reneging on these unfunded obligations. Prechter points out that the Fed is the ultimate narcissistic institution and always does what is best for the Fed. And hyperinflation would be the Fed committing suicide. If they destroy all value whatsoever to the USD, the Fed is quite out of business.

Furthermore, Williams keeps writing about foreign investors losing confidence in the dollar and dumping them. But he never says how. In a river? Buying gold, Euros, land, oil futures, pork bellies? How are these guys going to dump their dollars? He is very bullish on the Canadian dollar and the Swiss Franc. But UBS, which is in deep doodoo, is 8 times the size of the whole country of Switzerland, and Canada is in a bigger (soon to pop) real estate bubble than the US. Williams almost totally ignores credit and does totally ignore the shadow banking system, which is in a slow motion train wreck. If I had to choose the biggest fault in his argument, that would be it.

In the exciting climax section to his essay, subtitled "Hyperinflationary Great Depression", he does deal in some depth with some of the problems which the Fed would face instituting hyperinflation. He claims that after the crash, remaining cash would disappear and we would immediately enter a poorly organized barter system. He admits that there are probably about $400 billion in greenbacks in potential circulation inside the USA now, and he doesn't explain why they would either disappear or become worthless. While $400 billion is not going to run our economy normally, to say the least, it will buy quite a few eggs and radishes at depressed prices. He seems to be confusing FRN's with stuff like demand deposits. How is the cash going to disappear and how does it become worth less as demand deposits disappear through banks collapsing? One would assume this is a perfect scenario for cash as king, as in Great Depression v. 1.0.

Williams does build a strong case that the Fed has wanted inflation from its inception. But there is a huge difference between inflation and hyperinflation. The former is quite useful in extracting the wealth from the peasants and funneling it upward to their betters, but the latter is, quite obviously, the final debt rattle of the whole financial system. Williams does not distinguish between them. Not all con artists are suicide bombers.

Williams also fails to deal with exactly how Uncle Ben is going to pump a gazillion dollars into the economy with any velocity. He admits that doing it electronically is problematic as by then most of the people will have lost their credit card accounts. Printing it and dropping it from helicopters as Uncles Miltie and Ben have suggested also doesn't seem to fill the bill. Squirrels and birds would feather their nests with them.

Then he writes about runs on the banks and how the Fed would fly cash, hot off the press, into banks that were being run on. Even if this were to happen, which I doubt would last more than a few days in a systemic banking collapse, it would not be hyperinflationary as the Fed would just be replacing checking account credit, that had absconded to money heaven, with paper. In terms of the total credit and money supply, it would just be a push in Vegas vernacular.

Well folks, just read this final section for yourselves. If Williams were a mystery novelist, the critics would totally pan him for not pulling all the strings together at the conclusion. It's more like he builds a really strong case for mega deflation, pulls a magic wand out of his back pocket, makes a few passes with appropriate sounds ...... and puff - hyperinflation. Well, read it for yourself, and comment.

I enjoyed the essay, however, as it got my tiny 125cc, single cylinder brain firing at high rpm's, but as to the substance of the work, he just doesn't pull it together. Brings me back to my science days, when a researcher's data point to conclusion A, but the guy is totally invested in B, so somehow he twists the data to support B in a final paroxysm of cognitive dissonance.

As a counterpoint of sorts, I would like to point to another article, this on Zero Hedge by Doug Hornig, titled The Big Dead-Cat Bounce

Much shorter and well worth reading. Toward the end, Hornig writes:

"That means it’s likely, in the not_too_distant_future, that the government will be confronted with a very stark choice between defaulting on the debt or trying to inflate its way out. The former would kill off economic growth and likely launch a worldwide depression of epic proportions.

Disastrous as that would be, if the alternative is chosen and Washington’s printing presses beget hyperinflation, that would probably be worse. In a serious deflation, those who have saved for a rainy day can make it through okay. In hyperinflation, which unconstrained further spending could easily bring on, everyone loses. The truly prudent prepare, as best they can, for either eventuality."

(Well, that's exactly what I am doing by investing in Reverend Billy's Passbook to Heaven account. God is the ultimate hedge.)

What is interesting about this quote is that Hornig poses the question of hyperinflation or deflation as a very conscious political choice on the part of the oligarchs. Weimar chose hyperinflation out of revenge to screw the French. "You want blood money? Well here it is and you can wipe your butts with it." Uncle Ben doesn't strike me as a suicide bomber. When he lies in state, he expects his beard still to be immaculately groomed.

Below, for what it’s worth, are some of the notes and page references which I made when reading Williams’ article.

- Williams defines inflation and deflation in terms of prices and not the change in the sum of money credit and velocity. p 5

- However, he implicitly recognizes the Automatic Earth definition with: "Importantly, a sharp decline in broad money supply is a prerequisite to goods and services price deflation." p 21

- Using Williams's CPI, I calculated that the real rate of average price increases since 1982 averaged 13% a year. This would be what the MSM refers to as "inflation." Williams strongest asset is as a statistician who corrects BLS bullshit vis-a-vis the CPI and unemployment.

- Williams states that his adjusted CPI never fell below 5% rate of change since the financial crises while the BLS CPI went negative. I wonder how his statistics deal with the value of residential and commercial real estate collapse? This is a huge deflationary pressure either by price or money supply definitions. p 16

- For full disclosure, Williams states that he is a conservative Republican of the Libertarian wing. p 17

- Williams states that the actual federal deficit is currently at $9 trillion a year. I wonder exactly how he arrived at that figure? p 18

- Williams keeps repeating the phrase "dumping of dollars and dollar denominated assets" yet he does not define the other side of the trade. Real estate? Gold? Euros? Swiss Francs? Pork bellies? While Williams admits that the dollar has "soared" since the start of the financial crises, he writes this off to central bank manipulation, but offers no meaningful evidence. Seems contradictory. He repeats like a broken record that Bernanke wants to castrate the dollar, yet here, the central banks, of which the Fed is chairman of the board, suddenly gets into a huge manipulation to strengthen it on the forex markets. Hmm.... p 26

- "(2) Includes gross federal debt, not non_public debt is debt the government owes to itself for Social Security, etc., the obligations there are counted as "funded" and as such are part of total government obligations." p 29.

Is this correct? My understanding was that the Social Security Trust Fund was part of the $12T current public debt.

Michael Lewis: Wall Street Collapse A Story Of 'Mass Delusion'

It may be tempting to think Wall Street is full of criminals who got off easy during the financial crisis. But bestselling author Michael Lewis cautions against such an easy conclusion. "I think the story is much more interesting than that," he said during an interview on CBS's 60 Minutes. "I think it's a story of mass delusion."

The former bond trader is releasing a book this week called The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine. According to CBS, the result of his 18-month investigation attempts to explain, "how some of Wall Street's finest minds managed to destroy $1.75 trillion of wealth in the subprime mortgage markets."

Lewis told the network, "The incentives for people on Wall Street got so screwed up, that the people who worked there became blinded to their own long term interests. And because the short term interests were so overpowering. And so they behaved in ways that were antithetical to their own long term interests."

WATCH PART ONE:

WATCH PART TWO:

Goldman Sachs derivative liability = 33,823% of assets

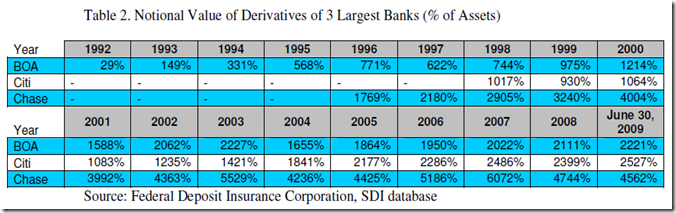

I have spoken at length here about the insidiousness of derivatives and Credit Default Swaps. So this new statistical reference frankly awed me. It is from a Levy paper on the recent shift over the last 50 years to a shadow banking system, that has largely replaced bank balance sheet lending with Money Managers. As I read this paper, while I am also reading ‘This Time is Different – eight centuries of financial folly’, there is little to feel good about in the apparent economic rebound that the government keeps telling us about.The data on derivatives is impressive. JPMorgan Chase, for example, held derivatives worth 6,072 percent of its assets at the peak of the bubble in 2007. The other two giants, Citigroup and Bank of America, although still far behind Chase, had 2,022 percent and 2,486 percent respectively. Goldman Sachs, the other giant, had an astonishing amount of derivatives on its balance sheets: 25,284 percent of assets in 2008 and 33,823 percent as of June 2009. Citigroup and BOA now have more of this risk on their books than before the crisis (FDIC SDI database).The part that awed me, is that BofA and Citi now have more derivative exposure than they did in 2007! Huh! What is Timothy Geithner being paid for? I have to admit after TARP and the apparent hands on approach I like most assumed things were being fixed, but apparently not.

This simply adds to the point that despite all the histrionics and efforts in Washington, nothing has been learned and the American Banking system is now at least at as much risk now as in 2007, pre crash.

Incidentally when trying to understand derivatives, simply assume off balance sheet debt. There is all kind of rationale as to why that off balance sheet debt is not dollar for dollar, but the important point is that no-one argues that derivatives are worth zero. There is an intrinsic liability that frankly few bankers can explain to you, so you must begin with the face value of the liability, and banks are guilty until proven innocent on that one.

As an accountant, the notion of off balance sheet debt is a contradiction in terms. Is it a liability? If yes, it should be on the balance sheet.

Goldman Sachs Demands Collateral It Won’t Dish Out

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co., two of the biggest traders of over-the- counter derivatives, are exploiting their growing clout in that market to secure cheap funding in addition to billions in revenue from the business. Both New York-based banks are demanding unequal arrangements with hedge-fund firms, forcing them to post more cash collateral to offset risks on trades while putting up less on their own wagers. At the end of December this imbalance furnished Goldman Sachs with $110 billion, according to a filing. That’s money it can reinvest in higher-yielding assets.

"If you’re seen as a major player and you have a product that people can’t get elsewhere, you have the negotiating power," said Richard Lindsey, a former director of market regulation at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission who ran the prime brokerage unit at Bear Stearns Cos. from 1999 to 2006. "Goldman and a handful of other banks are the places where people can get over-the-counter products today."

The collapse of American International Group Inc. in 2008 was hastened by the insurer’s inability to meet $20 billion in collateral demands after its credit-default swaps lost value and its credit rating was lowered, Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York at the time of the bailout, testified on Jan. 27. Goldman Sachs was among AIG’s biggest counterparties. Goldman Sachs Chief Financial Officer David Viniar has said that his firm’s stringent collateral agreements would have helped protect the firm against a default by AIG. Instead, a $182.3 billion taxpayer bailout of AIG ensured that Goldman Sachs and others were repaid in full.

Over the last three years, Goldman Sachs has extracted more collateral from counterparties in the $605 trillion over-the- counter derivatives markets, according to filings with the SEC. The firm led by Chief Executive Officer Lloyd C. Blankfein collected cash collateral that represented 57 percent of outstanding over-the-counter derivatives assets as of December 2009, while it posted just 16 percent on liabilities, the firm said in a filing this month. That gap has widened from rates of 45 percent versus 18 percent in 2008 and 32 percent versus 19 percent in 2007, company filings show.

"That’s classic collateral arbitrage," said Brad Hintz, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. in New York who previously worked as treasurer at Morgan Stanley and chief financial officer at Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. "You always want to enter into something where you’re getting more collateral in than what you’re putting out." The banks get to use the cash collateral, said Robert Claassen, a Palo Alto, California-based partner in the corporate and capital markets practice at law firm Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker LLP. "They do have to pay interest on it, usually at the fed funds rate, but that’s a low rate," Claassen said.

Goldman Sachs’s $110 billion net collateral balance in December was almost three times the amount it had attracted from depositors at its regulated bank subsidiaries. The collateral could earn the bank an annual return of $439 million, assuming it’s financed at the current fed funds effective rate of 0.15 percent and that half is reinvested at the same rate and half in two-year Treasury notes yielding 0.948 percent. "We manage our collateral arrangements as part of our overall risk-management discipline and not as a driver of profits," said Michael DuVally, a spokesman for Goldman Sachs. He said that Bloomberg’s estimates of the firm’s potential returns on collateral were "flawed" and declined to provide further explanation.

JPMorgan received cash collateral equal to 57 percent of the fair value of its derivatives receivables after accounting for offsetting positions, according to data contained in the firm’s most recent annual filing. It posted collateral equal to 45 percent of the comparable payables, leaving it with a $37 billion net cash collateral balance, the filing shows. In 2008 the cash collateral received by JPMorgan made up 47 percent of derivative assets, while the amount posted was 37 percent of liabilities. The percentages were 47 percent and 26 percent in 2007, according to data in company filings. "JPMorgan now requires more collateral from its counterparties" on derivatives, David Trone, an analyst at Macquarie Group Ltd., wrote in a note to investors following a meeting with Jes Staley, chief executive officer of JPMorgan’s investment bank.

By contrast, New York-based Citigroup Inc., a bank that’s 27 percent owned by the U.S. government, paid out $11 billion more in collateral on over-the-counter derivatives than it collected at the end of 2009, a company filing shows. The five biggest U.S. commercial banks in the derivatives market -- JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America Corp., Citigroup and Wells Fargo & Co. -- account for 97 percent of the notional value of derivatives held in the banking industry, according to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. In credit-default swaps, the world’s five biggest dealers are JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Frankfurt-based Deutsche Bank AG and London-based Barclays Plc, according to a report by Deutsche Bank Research that cited the European Central Bank and filings with the SEC.

Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan had combined revenue of $29.1 billion from trading derivatives and cash securities in the first nine months of 2009, according to Federal Reserve reports. The U.S. Congress is considering bills that would require more derivatives deals be processed through clearinghouses, privately owned third parties that guarantee transactions and keep track of collateral and margin. A clearinghouse that includes both banks and hedge funds would erode the banks’ collateral balances, said Kevin McPartland, a senior analyst at research firm Tabb Group in New York.

When contracts are negotiated between two parties, collateral arrangements are determined by the relative credit ratings of the two companies and other factors in the relationship, such as how much trading a fund does with a bank, McPartland said. When trades are cleared, the requirements have "nothing to do with credit so much as the mark-to-market value of your current net position." "Once you’re able to use a clearinghouse, presumably everyone’s on a level playing field," he said.

Still, banks may maintain their advantage in parts of the market that aren’t standardized or liquid enough for clearing, McPartland said. JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon and Goldman Sachs’s Blankfein both told the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission in January that they support central clearing for all standardized over-the-counter derivatives. "The percentage of products that are suitable for central clearing is relatively small in comparison to the entire OTC derivatives market," McPartland said.

A report this month by the New York-based International Swaps & Derivatives Association found that 84 percent of collateral agreements are bilateral, meaning collateral is exchanged in two directions.

Banks have an advantage in dealing with asset managers because they can require collateral when initiating a trade, sometimes amounting to as much as 20 percent of the notional value, said Craig Stein, a partner at law firm Schulte Roth & Zabel LLP in New York who represents hedge-fund clients.

JPMorgan’s filing shows that these initiation amounts provided the firm with about $11 billion of its $37.4 billion net collateral balance at the end of December, down from about $22 billion a year earlier and $17 billion at the end of 2007. Goldman Sachs doesn’t break out that category. A bank’s net collateral balance doesn’t get included in its capital calculations and has to be held in liquid products because it can change quickly, according to an executive at one of the biggest U.S. banks who declined to be identified because he wasn’t authorized to speak publicly.

Counterparties demanding collateral helped speed the collapse of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, according to a New York Fed report published in January. Those that had posted collateral with Lehman were often in the same position as unsecured creditors when they tried to recover funds from the bankrupt firm, the report said. "When the collateral is posted to a derivatives dealer like Goldman or any of the others, those funds are not segregated, which means that the dealer bank gets to use them to finance itself," said Darrell Duffie, a professor of finance at Stanford University in Palo Alto. "That’s all fine until a crisis comes along and counterparties pull back and the money that dealer banks thought they had disappears."

While some hedge-fund firms have pushed for banks to put up more cash after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, Goldman Sachs and other survivors of the credit crisis have benefited from the drop in competition. "When the crisis started developing, I definitely thought it was going to be an opportunity for our fund clients to make some headway in negotiating, and actually the exact opposite has happened," said Schulte Roth’s Stein. "Post-financial crisis, I’ve definitely seen a greater push back on their side." Hedge-fund firms that don’t have the negotiating power to strike two-way collateral agreements with banks have more to gain from a clearinghouse than those that do, said Stein.

Regulators should encourage banks to post more collateral to their counterparties to lower the impact of a single bank’s failure, according to the January New York Fed report. Pressure from regulators and a move to greater use of clearinghouses may mean the banks’ advantage has peaked. "Before the financial crisis, collateral was very unevenly demanded and somewhat insufficiently demanded," Stanford’s Duffie said. A clearinghouse "should reduce the asymmetry and raise the total amount of collateral."

Money can't buy you happiness, economists find

Inhabitants of wealthy countries tend to grow more miserable as their economy grows richer, according to research. Economists Curtis Eaton and Mukesh Eswaran found that while the richest people, such as footballers and bankers, could perk themselves up with a new pair of designer shoes or a sophisticated mobile phone. However, the bulk of the population who were unable to afford the latest status symbols were left unhappier by their inability to keep up.

As countries become wealthier, more value is attached to objects which are not strictly necessary for comfortable living, the researchers claim. People are then drawn into keeping up with the Joneses which results in less happiness for those who cannot afford the newest "must-have" items even if their wealth has increased. The nation’s sense of "community and trust" can then be damaged which, in turn, can affect the wider economy, the experts argued.

Prof Eaton, of the University of Calgary, and Prof Eswaran, of the University of British Columbia, concluded that, beyond the point of reasonable affluence, greater riches can make a nation collectively worse off. In their research, published in the Economic Journal, they said: "These goods represent a 'zero-sum game' for society: they satisfy the owners, making them appear wealthy, but everyone else is left feeling worse off. "Conspicuous consumption can have an impact not only on people's well-being but also on the growth prospects of the economy." The Canadian research follows in the footsteps of the 19th century Norwegian-American economist Thorstein Veblen. Prof Veblen coined the term "conspicuous consumption" and said it was a method by which people seek to set themselves apart.

Loan Squeeze Thwarts US Small-Business Revival

Thomas Harrison, chief executive of Michigan Ladder Co., has a plan that would contribute to the U.S. economic recovery: Expand the 108-year-old company, adding at least 20 jobs in the process. His chances of getting the loan of $300,000 or more he needs to do so, though, depend in part on what happens to folks like home builder James Haeussler. Both are customers of the same community bank, the Bank of Ann Arbor. Mr. Haeussler is struggling to repay $8.3 million he and a partner borrowed to build a residential community in nearby Saline, Mich. In this economic environment, the bank doesn't want to take a chance on what it sees as a risky new loan to Mr. Harrison.

"In a world where Jim Haeussler makes it, Tom Harrison will make it," says Timothy Marshall, the bank's president. "But it's not prudent to do both loans at this point in time. We're in a more risk-averse mode." Mr. Marshall's reluctance sheds light on a problem looming over the economy. A year and a half after the financial crisis hit, the U.S. credit machine is still malfunctioning. During the boom, credit was too abundant. Now the pendulum has swung. With an eye toward limiting such swings, Sen. Christopher Dodd is expected to unveil a bill Monday that would be especially tough on big banks while preserving the Fed's regulatory role, but the bill's prospects remain uncertain.

For a recovery to take hold, hundreds of thousands of small businesses must find the confidence to expand and create jobs. But when they get to that point, the local banks they depend on—worried about borrowers' financial strength, scrutinized by regulators and slammed by souring real-estate loans—might not be willing or able to provide the credit they need. While big companies have been able to borrow in bond markets, smaller companies rely mainly on bank credit, which has been shrinking. In 2009, total lending by U.S. banks fell 7.4%, the steepest drop since 1942. In all, the credit pulled out of the economy by banks since the downfall of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 amounts to about $700 billion, more than double the amount so far distributed under President Barack Obama's $787 billion stimulus program.

"It's a dismal situation," says Diane Swonk, chief economist at Chicago-based financial-services firm Mesirow Financial. "Banks won't lend to businesses because they're afraid they'll go bad, but that can become a self-fulfilling prophecy." The dearth of credit for small businesses could have a big effect on prospects for restoring the 8.4 million jobs lost since the recession began. From 1992 through the beginning of the latest recession, companies with fewer than 100 employees accounted for about 45% of net job growth, according to Labor Department data.

Policy makers have been looking for ways to reopen the spigot. President Obama has proposed creating a $30 billion fund to support small-business lending. Last month, in an unusual show of solidarity, the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and other state and federal regulators issued a joint statement urging banks to continue lending to credit-worthy small enterprises. Making sure small firms get access to credit "is crucial to avoiding a Japan-type scenario of persistent stagnation," says Mark Gertler, a New York University economist who has done seminal research with Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, then a Princeton University professor, on how troubles with bank lending can aggravate economic downturns.

Getting banks to lend more won't be easy, given the rising tide of defaults on loans made to finance housing developments, office buildings, shopping malls and other commercial real estate. Deutsche Bank expects banks to suffer at least $250 billion in losses on such loans, with about half coming in the next few years. Together with an estimated $250 billion in further charge-offs on home mortgages, that's more than double banks' current reserves against losses on all types of loans. The stakes are particularly high for community banks, which tend to be much more active in commercial real estate than their larger counterparts. As of December 2009, such loans comprised about 42% of all loans held by the 7,344 banks with less than $1 billion in assets, compared to about 17% for the hundred or so banks with more than $10 billion in assets.

Some bankers say policy makers' desire to encourage lending isn't always reflected on the ground, where they say bank inspectors are getting tougher about lending standards. "For the first time in my 37 years in banking, we're having to say to our clients that we're not sure this will pass muster with the regulators," says Larry Barbour, president and chief executive of North State Bank in Raleigh, N.C. "That's not healthy." Washtenaw County, Mich., which includes Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti and Saline, offers a glimpse of how the cycle of economic malaise and shrinking credit is playing out across the country. The county includes the Willow Run plant, where Ford Motor Co. once produced the B-24 Liberator bombers that helped win World War II, the University of Michigan football stadium, and hospital complexes and high-tech start-ups in Ann Arbor. As of December, Washtenaw's unemployment rate stood at 9%, close to the national average.

Michigan Ladder's Mr. Harrison, 44 years old, remembers vividly the day in September 2008 when the recession hit home. The company, which manufactures wooden ladders and distributes imported aluminum and fiberglass models, had been doing well despite the financial crisis. Sales were up 6% over the previous year, and Mr. Harrison had expanded the company's staff to about 28, from 20 at the beginning of the year. But during the week of Sept. 15, the company's largest supplier of aluminum and fiberglass ladders suddenly refused to deliver ladders unless it was paid in advance. Within days, says Mr. Harrison, Michigan Ladder lost as much as $1 million of the supplier credit on which it relied to pay for raw materials and maintain its inventory of ladders. At the same time, its customers started failing to pay for ladders it had already delivered.

"Literally overnight, the whole world changed for us," says Mr. Harrison. "It was simply too much of a shock—too much of a change, too quickly." He laid off eight workers in December 2008 and another eight in 2009 as sales fell 40%. Mr. Harrison has since lined up new credit from suppliers, and he says sales are on track to rise 15% this year. He thinks the time has come to implement the expansion project he shelved when the crisis hit. The plan: Produce in Michigan the aluminum and fiberglass ladders he currently imports from places such as Mexico and China. He already has the customers, and he calculates that manufacturing in Michigan will actually boost his profit margins, in part because the savings on shipping will offset the higher cost of U.S. labor.

"We can do this," he says. "We can be a low-cost producer, and we will have a made-in-USA product, which we think will have some appeal to people." The Bank of Ann Arbor is Mr. Harrison's best bet to finance his project. Larger banks typically don't deal with companies the size of Michigan Ladder. Also, Bank of Ann Arbor, which has $543 million in assets, has weathered the crisis much better than most of its peers. It turned profits every year, expanded overall lending and declined the support of the government Troubled Asset Relief Program.

The bank has made loans to finance expansions for some of its stronger customers, such as Solohill Engineering, which makes products used in the manufacture of vaccines and more than doubled sales in 2009. Nonetheless, says its president, Mr. Marshall, fears about a weak recovery are prompting even healthy banks to be careful, a trend he recognizes could help make those fears a reality. "It's kind of a vicious cycle," he says. "Anytime you're in an economic environment like we are, bankers are going to be more conservative."

One of bankers' main concerns is the damage the recession has done to many companies' finances. Values of real estate and other things small business owners can put up as collateral for loans have fallen so far, so fast, that many businesses have little to offer. Also, a year or more of losses have eroded the value of owners' stakes in companies, leaving less of a cushion against bankruptcy. Mr. Marshall says such financial concerns are a big reason he's not ready to lend to Mr. Harrison, who says his company took heavy losses in 2008 before returning to profitability in 2009. Mr. Harrison says he's exploring ways to raise new money from investors, but so far to no avail. "It's not reasonable to expect that [the Bank of Ann Arbor] can make up for all the credit companies like ours have lost," he says.

Mr. Harrison's credit difficulties also are linked to the travails of other borrowers such as Mr. Haeussler, the 51-year-old president of Peters Building. In 2005, he and a partner began developing a 625-acre piece of land known as Saline Valley Farms, the site of a cooperative farm in the mid-1900s. The downturn hit Mr. Haeussler hard in 2007, when home builder Toll Brothers called with bad news: It wouldn't exercise its option to purchase 93 luxury-home lots, the entire first phase of the Saline Valley Farms project. When the $8.3 million loan he and a partner had taken out to grade the lots and build infrastructure came due in late 2008, they still owed $6.7 million and had 76 empty lots, the estimated value of which had fallen to about $1.4 million.

"It was perfectly wrong timing," says Mr. Haeussler. Losses on loans to developers such as Mr. Haeussler have taken a toll on community banks, eroding their capital and limiting their capacity to make new loans. Bank of Ann Arbor has moved more quickly than other banks to recognize losses, charging off nearly one-quarter of its construction and development loans in 2009. That compares to about 5% for all banks. In its remaining portfolio of such loans, about 6% are delinquent, compared to about 16% for all banks.

Many community banks are renegotiating troubled real-estate loans. In Mr. Haeussler's case, the Bank of Ann Arbor cut a deal: In return for a four-year extension, Mr. Haeussler and his partner more than quadrupled the amount of collateral backing the loan, putting up the entire Saline Valley Farms project and more. Even with the added collateral, the bank charged off $2.1 million of the loan, effectively recognizing that it may never get the money back.

The bank figures that giving Mr. Haeussler more time increases the odds he will pay off his loan. But such deals tie up cash on what essentially are bets that existing borrowers will make it through. That leaves banks, including Bank of Ann Arbor, with less appetite to make new loans to customers like Mr. Harrison, who doesn't have the resources Mr. Haeussler and his partner used to secure their loan. Mr. Haeussler, for his part, says he's trying not to think too much about all that's hanging in the balance, which could include his entire business. "It's a little unnerving at times," he says. "But you just have to put your head down and work through it."

Leading Countries Face a Debt 'Balancing Act'

Moody's sees ratings challenges for U.S., U.K., France, Germany

The four large triple-A-rated countries—the U.K., the U.S., France and Germany—face "an increasingly delicate balancing act" as they consider spending cuts to reduce government debt, Moody's Investors Service said in a review of these country's ability to retain their top credit-rating status. The credit-rating company repeated that there was no immediate risk of a downgrade of the big triple-A-rated countries, although the slight risk they could fail to get their finances under control, and thus be downgraded, has increased. Moody's concluded that "on balance, we believe that the ratings of all large triple-A governments remain well positioned—although their 'distance-to-downgrade' has in all cases substantially diminished."

All large triple-A governments "have the capacity to rise to the challenges they face," the rating agency said in its quarterly report on triple-A-rated sovereign issuers. A downgrade to any of these countries, as well as being viewed as a national humiliation, could significantly increase the government's interest bill. Moody's noted that while the global economy seems to be recovering, much of the rebound has bypassed the four countries, dashing their hopes that economic growth would help solve their debt problems and meaning that government spending would have to be cut. This has created "substantial execution risk" as countries try to make cuts without derailing the recovery and "damaging a government's main asset: its power to tax," the rating agency said.

Governments can't dodge the need for cuts by keeping stimulus packages in place and going for growth, Moody's warned, because this could test the confidence of financial markets, or of central banks, which might move to combat inflation expectations by raising interest rates. "At the current elevated levels of debt, rising interest rates would quickly compound an already complicated debt equation, with more abrupt rating consequences a possibility," Moody's said.

Still, even if a large triple-A-rated country reached the level at which interest payments reach 10% of revenue, Moody's said it wouldn't automatically lead to a downgrade. Instead, the ratings company said, it would look at the concept of "debt reversibility," or the degree to which governments are able and willing to get the debt level under control over a period of five to seven years. This, in turn, is linked to a country's political system and its ability to inflict deep spending cuts on itself.

Among the four largest triple-A-rated sovereigns, France has the lowest "debt reversibility margin", at 1%, Moody's said. This could mean that a rise in France's debt-affordability ratio above 11% would have rating implications, because a return to single digits in the foreseeable future would look unlikely unless the French government "demonstrated a reaction capacity well above that observed so far." Germany's margin is higher, at 2%. The U.K. and the U.S., where debt affordability is most stretched, enjoy margins of 3% and 4% respectively. However, Moody's said its figures for debt-reversibility margins aren't "hard triggers for rating decisions."

In its country-by-country assessments, Moody's said that for the U.S., a rise in the proportion of revenue that the government spends servicing its debt over the next 10 years, as outlined in the federal budget in February, would put the U.S. government's triple-A rating under pressure. However, it said federal debt affordability has "for the time being" not deteriorated despite the U.S.'s rising deficit, and isn't yet at a level that threatens the rating. Including state and local government debt, the affordability of general government debt would exceed 10% under Moody's baseline scenario in 2013. Under the agency's adverse scenario, it would exceed 14%, taking it beyond the possible buffer provided by Moody's 4% debt-reversibility margin.

"Both federal and general government affordability is growing more vulnerable to any shift in market confidence that would lead to higher interest rates than assumed in these projections," Moody's said. The 10-year outlook in the budget shows a continuous rise in the debt-affordability ratio, to around 18%, roughly the peak level when interest rates were high in the 1980s. "If such a trajectory were to materialize, there would at some point be downward pressure on the Aaa rating of the federal government," Moody's said. The U.S. has said it will set up a National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, which will recommend ways to confront the federal deficit, but Moody's said that "the politics" of implementing any suggestions "remain uncertain."

For the U.K., it said, the top-notch credit rating depends primarily on investor confidence that "resolute action" will be taken to bring debts under control, rather than when exactly such steps will begin. Moody's also warned that if U.K. government bond yields move significantly higher, it "would not be consistent" with a triple-A rating over time. It said the suspension of the Bank of England's bond-buying plan poses an upside risk in this regard. Germany's debt-affordability ratio is projected to stay well below double digits for the next two to three years, Moody's said. The French government's triple-A rating faced no near-term danger because debt affordability should stay in the triple-A range "under most plausible scenarios," the report said.

The $2 Trillion Hole

Like a California wildfire, populist rage burns over bloated executive compensation and unrepentant avarice on Wall Street.Deserving as these targets may or may not be, most Americans have ignored at their own peril a far bigger pocket of privilege -- the lush pensions that the 23 million active and retired state and local public employees, from cops and garbage collectors to city managers and teachers, have wangled from taxpayers.

Some 80% of these public employees are beneficiaries of defined-benefit plans under which monthly pension payments are guaranteed, no matter how stocks and other volatile assets backing the retirement plans perform. In contrast, most of the taxpayers footing the bill for these public-employee benefits (participants' contributions to these plans are typically modest) have been pushed by their employers into far less munificent defined-contribution plans and suffered the additional indignity of seeing their 401(k) accounts shrivel in the recent bear market in stocks.

And defined-contribution plans, unlike public pensions, have no protection against inflation. It's just too bad: Maybe some seniors will have to switch from filet mignon to dog food.

>Most public employees, if they hang around to retirement, can count on pensions equal to 75% to 90% of their pay in their highest-earning years. And many public employees earn even more in retirement than their best year's base compensation as a result of "spiking" their last year's income by working ferocious amounts of overtime and rolling in years of unused sick and vacation days into their final-year pay computation.A survey by the watchdog group California Foundation for Fiscal Responsibility found that some 15,000 Golden State public employees are knocking down $100,000 or more, while some 200, mostly police and fire chiefs and school administrators, are members of the $200,000-a-year-and-up club.

THE PROSPECTS ARE BLEAK for many state and local governments as a result of all this. According to a survey last month by the Pew Center on the States, a nonpartisan research group, eight states -- Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, Rhode Island and West Virginia -- lack funding for more than a third of their pension liabilities. Thirteen others are less than 80% funded.Governments could fill that gap by raising property, sales and income taxes, but most are wrestling with huge revenue shortfalls in trying to balance their budgets.

The more likely outcome is dramatic cuts in essential services, such as police and fire protection, health spending, education and infrastructure improvements, in order to cover ballooning pension payments. State and municipalities, after all, must do something: Most have a legal obligation to pay out earned pension benefits. And some don't even have the courage to switch new teachers, bureaucrats and police to a defined-contribution system, to prevent the funding problem from worsening as time rolls on.

THUS, MORE DEBT DEFAULTS and bankruptcy filings probably lie ahead, unsettling the $2.7 trillion municipal-bond market. The possibility of taxpayer revolts and likely insolvencies has shaken some investors' confidence in general-obligation bonds -- those backed by the "full faith and credit" of the states or localities. Once the gold standard for munis, GOs are under a cloud in financially troubled areas.The size of the legacy-pension hole is a matter of debate. The Pew report puts it at $452 billion. But the survey captured only about 85% of the universe and relied mostly on midyear 2008 numbers, missing much of the impact of the vicious bear market of 2008 and early 2009. That lopped about $1 trillion from public pension-fund asset values, driving down their total holdings to around $2.7 trillion.

Other observers think the eventual bill due on state pension funds will be multiples of the Pew number. Hedge-fund manager Orin Kramer, who is also chairman of the badly underfunded New Jersey retirement system, insists the gap is at least $2 trillion, if assets were recorded at market value and other pension-accounting practices common in Corporate America were adopted.

Finance professors Robert Novy-Marx at the University of Chicago and Joshua Rauh of Northwestern University asserted in a recent paper that the funding gap for state pension plans alone might exceed $3 trillion, in part because state funds are using an unrealistic long-term annual investment return of 8% to compute the present value of future payments to retirees, as is permitted in government standards for pension-fund accounting.

This establishes a "false equivalence" between pension liabilities and the likely investment outcomes of state investment portfolios, which are increasingly taking on more risk by beefing up their exposure to stocks, private-equity deals, hedge funds and real estate. Using a much lower expected return -- say, one at least partially based on the riskless rate of return on government securities -- would both properly and dramatically boost the present value of the pensions' liabilities while decreasing their likely ability to meet them. The academic pair, using modern portfolio theory, claim that state funds, as currently configured, have only a one-in-20 chance of meeting their obligations 15 years out.

MAKING THE STATE AND local pension problem all the more trying is that government entities can do little to wriggle out of their exposure, even if spending on essential services is threatened. The constitutions of nine states, including beleaguered California and Illinois, guarantee public-pension payments. And most other states have strong statutory or case-law protections for these obligations. "One shouldn't be surprised by this, since state legislators, state and local judges and the state attorneys general are beneficiaries of the self-same public pension funds that they've done so much to promote and protect," Orin Kramer notes wryly.True, a dozen or so states, including New York, Nevada, Nebraska, Rhode Island and New Jersey, are attempting reforms such as raising retirement ages, cutting pension-benefit formulas, boosting employee contributions, curbing income "spiking" and partially switching employees to less costly defined-contribution plans. But these changes affect almost exclusively new employees and do little to solve the existing funding gap.

The municipal-bond market, for one, seems vulnerable to the growing public pension mess. Warren Buffett, in his 2007 Berkshire Hathaway annual report, inveighed against the "woefully inadequate" funding in many public pension funds to meet "huge" promised payments to retirees. True to his word, Buffett has sold precious little municipal-bond insurance in a Berkshire Hathaway unit he set up for that purpose in 2008.

Jim Spiotto, a muni-bond restructuring expert at the Chicago law firm Chapman & Cutler, argues the pension crisis is quickly reaching a tipping point after being ignored for years.

"I just can't believe that any bond issuer would be willing to suffer the stigma of defaulting on their general-obligation debt as a result of having to fund future pension obligations, but such a situation is no longer beyond the realm of possibility," he observes.

For proof, look no further than the San Francisco Bay city of Vallejo, which filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy in 2008 as a result of insolvency.

The California municipality, which has 120,000 residents, is proposing a three-year moratorium on all interest and principal payments on the $53 million of municipal debt that is backed by its general fund. But it is keeping fully intact its $84 million in pension-fund obligations.

SOVEREIGN DEFAULT IS A hot topic these days. With Greece tottering and other European countries in fiscal distress, some have even voiced the possibility that a U.S. state -- also considered a sovereign entity -- could suffer a general-obligation debt default.Says Todd Zywicki, a law professor at George Mason University: "In many ways, some of our states are like General Motors before its bankruptcy, suffering from falling revenue, borrowing money to cover operating expenses and operating under crushing legacy health and pension liabilities. It's entirely possible, given the gigantic size of the pension liabilities, that some states might do what was once the unthinkable at GM and default."

Such assessments might be alarmist. A rebound in the U.S. economy and a continued rally in stocks would do a world of good for ailing public pension funds. And only one state -- Arkansas in 1934 -- has defaulted on its GO bonds in the past century with their holders suffering losses. Arkansas, however, was a special case. In addition to the Great Depression, it was ailing from large local debts it had assumed as a result of catastrophic floods in the 1920s.

But what if the stock-market rally falters, the economy doesn't return to full health, jobs remain scarce and tax revenues remain depressed?

According to muni-bond expert Spiotto, most defaults at the municipal level have come as a result of shortfalls in the revenue generated by quasi-public projects, such as hospital additions, sports facilities, housing-development infrastructure, giant garbage incinerators and the like, rather than systemic financial failures of major localities like Vallejo. And even after New York City's debt default in 1975, municipal-debt holders were ultimately made whole.

NONETHELESS, SOME MAJOR BOND investors are altering their strategies in light of the impending pension crisis.John Cummings, the executive vice president in charge of the $27 billion muni portfolio at giant fixed-income house Pimco, says it is underweighting the GOs of the "poster boys" of debt problems and pension under- funding -- California, Illinois, New Jersey and Rhode Island. Revenue bonds -- those backed by the money generated by a specific source -- have become more attractive to Pimco, particularly if they're backed by essential services like water authorities, sewer systems or school districts and have dedicated, stable revenue streams that can't be diverted to other uses. Revenue bonds funding new projects could be considerably more risky.

Says Cummings: "We want to stay as far away as possible from bonds that depend on the politicians and general funds of financially shaky states and smaller issuers unless the price is right. You ask California Treasurer Bill Lockyer, one of the greatest bond salesman ever, about the state's pension situation and all you get back is a thousand-yard stare and a quick change of subject. That's concerning."

A spokesman for Lockyer told Barron's that the treasurer "realizes that the pension-underfunding problem is serious, unsustainable and therefore needs to be fixed. He wants to ensure that any reform is fair to all stakeholders, including the state, public employees and taxpayers."

No one, of course, would dispute that public servants deserve adequate retirements, particularly the 25% to 30% that lack Social Security coverage. But the old saw that rich retirement packages are a necessary inducement to attract good employees to public payrolls because of below-average pay scales no longer is true.

According to the latest compensation survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average state and local employee outearns his counterpart in the private economy with an hourly wage of $26.11, versus $19.41. That's before benefits (pensions, health care, paid vacations and sick days and leaves) drive the disparity even higher, to $39.60 an hour for public employees and $27.42 for private workers.

Even if one looks at pay received by so-called management and professional employees in each realm, fat benefits in the public sector drive the total compensation received by state and local managers to almost dead-even with private-sector managers -- $48.15 versus $48.17.

THE CURRENT STATE AND local pension crisis has many fathers. State and local governments have been under-funding their pension systems for a decade or more, under the misapprehension that the stock-market boom of the 1990s would continue and bail out any shortfalls. The underfunding has continued with a vengeance over the past two years as budgets were slashed to eliminate deficits.For example, last year New Jersey, under Gov. Jon Corzine -- a financially savvy former Goldman Sachs chief -- contributed only $105 million, instead of an actuarially determined $2.3 billion. In all, states and localities kicked in $72 billion in fiscal 2008, far short of adequate funding levels of $108 billion, according to the recent Pew study.

Such behavior is only encouraged by the fact that state and local governments are allowed as much as 30 years to close funding gaps. So it's easy for politicians to kick the can forward, avoiding the pain of boosting taxes and making hard spending decisions. The 30-year amortization periods have an evergreen nature, being renewed and invoked almost every year as the compounding of pension obligations works relentlessly against units of government.

Then, too, pension funds are being hit by baby-boomer retirements. A report from the National Association of State Retirement Administrators underlines this impact: It found that in 2008, for every state retiree collecting benefits, only 2.02 current workers were contributing to pension systems, compared with 2.45 in 2001.

Besides the politicians, the primary culprits are the public-employee unions, which have used their growing power to dramatically enhance pension benefits. They curry favor with sympathetic politicians, lavishing them with large donations and manning campaign phone banks. They also engage in full-court-press lobbying at all levels of state and local government.

One would think legislators or managers in state, county and local governments would protect the taxpayer by bargaining hard. But they clearly don't, because of inherent conflicts of interest.

Nearly all public employers, regardless of their position, benefit from the very same pension programs, either directly or indirectly. Legislators in the main receive the same pension benefits that they lavish on other public employees. And administrators, though subject to independently negotiated contracts, use enriched union pension plans as a valuable bargaining wedge. So there's little incentive to fight the unions with much vigor.

In fact, bad behavior abounds on both sides of the table when it comes to pensions. Plunder!, a recently published book by California journalist Steven Greenhut, details a number of ploys that both workers and management employ to goose their retirement checks. A favorite, he asserts, is income spiking. In the year before they retire, California police, firefighters and prison guards typically start notching hours and hours of overtime that has been reserved for them by less senior colleagues. Whatever they make in that final year is used in the formula that determines the monthly retirement check. Golden State, indeed.

OTHER ABUSES DETAILED in the book include widespread "double-dipping." Public employees can start collecting their full pensions while returning to their old job as consultants. Alternatively, they can take another public-sector job to earn credit toward yet another pension.Stories are rife around the country of various pension hijinks by public employees. A Contra Costa Times article bemoaned the artistry of a retired local fire chief in San Ramon, Calif., who boosted his annual pension from $221,000 a year to $284,000 by getting credit in his final earnings for unused vacation and sick leave.

In Illinois, veteran police with more than 12 years of service receive annual longevity pay boosts of 4% to 5% in addition to other salary increases. In some local departments, these boosts are all awarded as a 20% bump-up in the first couple months of the year, rather than prorated evenly throughout the year. This, of course, helps police in those jurisdictions get a 20% jump in their presumed compensation -- and, therefore, their pensions -- if they time their retirement date properly.

VALLEJO, CALIF., HAD NO CHOICE but to file a Chapter 9 bankruptcy in 2008 after property-tax revenue collapsed in the housing bust and a major employer -- the U.S. government's Mare Island Ship- yard -- closed. With the tax base hammered, rich public-employee contracts granted in better times were devouring more than 90% of the city's budget.Though Vallejo is still months away from getting a court decision on whether it can go ahead with its debt-adjustment plan, it has succeeded through contract renegotiations and major layoffs in cutting its employee costs by nearly a quarter.

But the fallout has been brutal. Employee health-care benefits have been decimated. Holders of the city's municipal bonds are unlikely to get all their money back. And violent crime rates have shot up dramatically as a result of reductions in its police force from 158 to 104 officers.

The only thing that will be left untouched? The very thing that tipped the California city into Chapter 9 -- its $84 billion in future pension obligations.

Lehman balance sheet massaging may not be unusual

On Wall Street, massaging the balance sheet is a time-honored practice. But did Lehman Brothers Holding Inc cross a line in the routine manipulation of its balance sheet, as described by an independent examiner? That is the central question to emerge from the examiner's report, released late on Thursday by the bankruptcy court in Manhattan, which details examples of Lehman concealing assets and liabilities through accounting techniques.

Thomas Baxter, general counsel of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, one of the main banking regulators, told the examiner, Anton Valukas, that he was generally aware of firms using "balance-sheet window dressing," but had no specific information on Lehman. Banks have wrestled with this issue for years. The old Bankers Trust, for instance, struggled to fend off bank clients that wanted to use BT to help conceal assets, said Ray Soifer, a consultant who previously worked at BT and sat on a task force designed to reduce that business. "Reducing leverage is something that banks do. It's cosmetic," Soifer said.

In 2003, an internal review into accounting irregularities at Freddie Mac found the government-sponsored mortgage finance firm had periodically rented out its balance sheet to a Credit Suisse Group AG mortgage trader.

The review found that Freddie Mac entered into a series of deals with Credit Suisse that allowed the investment bank's trading desk to "park" some $8 billion in mortgage-backed securities on the mortgage firm's balance sheet. Over the years, one common trick has been to borrow money at the beginning of the quarter and invest it in short-term bonds that mature before the end of the quarter. When the bonds mature, the bank pays back its debt and it has fewer assets and liabilities.

The upshot is that the bank generates more profit off what appears to be fewer assets, giving it a better return on assets, a commonly watched measure of profitability. One former chief executive at a bank noted this method can goose earnings higher, but is terrible for the company long term because it does not build the overall franchise. For commercial banks, regulators caught onto this trick years ago, which is why banks typically report average assets during the quarter in addition to assets at the end of the quarter, both to the public and to regulators.

But major investment banks did not have that obligation and, even now, often do not report their average assets to investors. "Nobody knows if other banks are doing this kind of thing," said Brad Hintz, an analyst at Sanford Bernstein who was Lehman's Chief Financial Officer in the 1990s. But he said the question is sure to come up in conference calls for Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

HOW IT WORKED

The mechanism that Lehman used for concealing assets and liabilities was much more complicated than borrowing at the beginning of the quarter and paying down debt at the end. It involved a series of short-term transactions similar to repurchase or repo deals, which entail selling assets and agreeing to buy them back in the future, according to the examiner's report. Lehman's deals were known as Repo 105 transactions. But instead of treating them as financings, Lehman classified these repo deals as "sales," which permitted the investment bank to keep the transactions off balance sheet.

Here is how it worked: Lehman essentially transferred assets to its London unit, which was the only jurisdiction where the bank could get lawyers at Linklaters to sign off on the deals. At the end of a quarter, Lehman would sell high quality assets to a counterparty -- the examiner's report mentions multiple European and Japanese banks -- for cash. The investment bank typically got cash equal to about 5 percent less than the face value of the asset. Lehman used the cash to pay down debt. At the start of the next quarter, Lehman would buy back the assets and borrow funds again. The net impact was the bank had lower assets and liabilities, making it appear to have less debt relative to its equity than it really did.

These transactions may have started out small in 2001, but by 2008 Lehman was using them to move big chunks of assets. The bank did about $50 billion of these transactions in the second quarter of 2008, which reduced its reported assets by about 7 percent, based on the company's financial statements for that quarter. That reduced its leverage ratios by nearly 2 points. The massaging allowed Lehman's leverage numbers to look much better than competitors. According to data compiled by Bernstein's Hintz, Lehman's net leverage ratio was 14.7 in the second quarter of 2008, compared with 20.8 for Goldman Sachs. Net leverage excludes repo assets and looks at assets compared with equity.

MORE MASSAGING

Lynn Turner, a former chief accountant for the Securities and Exchange Commission and now senior advisor to the consulting firm LECG, said the decision by Lehman executives to make greater use of Repo 105 is consistent with what companies do when they get themselves into trouble. "Companies never just fudge it a little bit," said Turner. "They start out just doing it a little bit and over time it grows and grows." While Turner said he was not aware of the Repo 105 transactions during this time at the SEC, he said it is fair "to wonder if anyone else is doing it." Turner added: "No one is going to stand up and say so."

Could Lehman be Ernst & Young's Enron?

Ever since the fraud at U.S. energy trader Enron Corp brought down accounting firm Arthur Andersen eight years ago, global auditing firms have worried that a major misstep could be fatal. Over the past few years, the firms have pushed for liability caps on litigation and settled dozens of cases, all amid concerns that each of the "Big Four" accounting firms faces potential litigation from undetected frauds at large public companies that could destroy them.

Ernst & Young became the latest auditor to come under fire this week after the court-appointed examiner in the Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc bankruptcy said the audit firm did not challenge accounting gimmicks that allowed Lehman to hide some $50 billion in assets in 2008, while claiming it had reduced its overall leverage levels. "As an auditor, you're always concerned when you're auditing a large company that ultimately fails," said Lynn Turner, a managing director in the forensic accounting practice at consulting firm LECG and former chief accountant of the Securities and Exchange Commission. "But a lot of those do occur where the auditors come out OK and the auditors aren't at risk -- obviously in this case the examiner thinks differently," Turner added.

At issue is a repurchase and sale program called Repo 105, which Lehman used without telling investors or regulators, and the examiner concluded was used for the sole purpose of manipulating Lehman's books.

In the examiner's report Lehman executives described the Repo 105 as everything from "window dressing" and an "accounting gimmick" to a "drug." According to the examiner's report, Ernst & Young's lead partner on the Lehman audit said the firm did not "approve" the Repo 105 accounting policies, but rather "became comfortable" with its use.

Lehman, which filed the largest U.S. bankruptcy case in history on September 15, 2008, is likely to use some of the examiner's claims to pursue lawsuits against those it believes are responsible for the investment bank's collapse. "This is like the horses getting out of the starting gate on the track -- the lawyers are going to sue the pants off anyone and everybody involved," said Anthony Sabino, a securities law professor at St. John's University's Tobin School of Business. Bryan Marsal, chief executive of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc and co-founder of restructuring firm Alvarez & Marsal, said through a representative that Lehman "will carefully evaluate it in the coming weeks to assess how it might help us in our ongoing efforts to advance creditor interests."

Lehman's examiner, Anton Valukas, found the repo transactions to be partly responsible for Lehman's demise, and said Lehman may have "colorable claims" against Ernst & Young for failing to notice that the repos lacked a business purpose. Auditors are supposed to "look at the substance" of such transactions in addition to seeing whether they have actually complied with U.S. accounting rules, Turner said, noting that he has not seen anything that would prove to him that the Repo 105 transactions complied with U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles.

Ernst & Young said in a statement: "Our last audit of the company was for the fiscal year ending November 30, 2007. Our opinion indicated that Lehman's financial statements for that year were fairly presented in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), and we remain of that view." "After an exhaustive investigation the examiner made no findings in his report that Lehman's assets or liabilities were improperly valued or accounted for incorrectly in Lehman's November 30, 2007, financial statements." According to the examiner's report, Ernst & Young had just started planning for its year-end audit of Lehman, when the firm collapsed into bankruptcy. "They are going to say, hey, we got hoodwinked like everybody else," Sabino said. "They've got defenses. For the directors and the officers, they're in a much tougher spot."

But most troubling for the auditors could be allegations in the examiner's report that Ernst & Young did not inform the audit committee on Lehman's board about a whistleblower who had expressed concerns about the repos to them. For Ernst & Young, the firm has previously faced similar allegations that it failed to notify a board of directors when it discovered potential problems in a tangle with U.S. securities regulators over its audits of health club operator Bally Total Fitness. In December, the Big Four firm agreed to pay the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission an $8.5 million fine, one of the highest settlements ever paid by an accounting firm.

Fines are not the only cost the firm might face, however. "If nothing else, it's perception -- this is going to cost them a whole lot in legal fees, and it's damaging to their reputation," Sabino said.

Further Lehmans revelations blocked by Barclays

Further damaging revelations about the collapse of Lehman Brothers are being held up in the US courts by Barclays. A 2,200-page examiner’s report into the collapse of the 158-year old institution, published last week, uncovered in forensic detail evidence that Lehman used "balance sheet manipulation" to mislead investors and regulators. It is expected to fuel a series of lawsuits that former Lehman executives and their auditors are already facing in the US courts.

The scathing report was described as "one of the most extraordinary pieces of work product I have ever encountered", by Judge James Peck, who commissioned it as part of his handling of the Lehman bankruptcy. Judge Peck added that the report, by New York City attorney Anton Valukas, "reads like a bestseller". Now legal sources say there is more to come with the publication of the millions of pages of Lehman e-mails, internal company files and documentary evidence from third parties that formed the basis of the report.

A court hearing will take place soon, possibly as soon as April 1, in which the examiner’s team is expected to argue for the release of these "underlying documents". "All of the parties have agreed to allow those documents given to [the examiner] under confidentiality agreements to be made public, with two limited exceptions that we are working out," a person familiar with the matter said.

The objectors include Barclays, which is concerned that some of the information on Lehman extracted from its databanks by Mr Valukas’ team of 70 lawyers may also contain commercially sensitive proprietary data that the bank does not want released because it involves clients. As Mr Valukas wants to make his findings as open as possible by putting up web links to all of the available material, a way is being sought through the courts to put the material, minus the commercially sensitive data, online.

The hearing is another headache for Barclays, which is currently being sued by the Lehman estate, currently going through bankruptcy, for the return of a $5 billion "windfall" it alleged was made buying Lehman’s brokerage. Barclays has disputed this sum, saying it was owed money on the deal. Mr Valukas’ report concluded that Barclays may have received "a limited amount of assets" improperly, including office equipment, during the transaction.

The other party objecting to publication of the underlying documents is the US Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), a federal bank regulator established in 1989 in response to another financial crisis – the savings and loans disaster, is also seeking redactions, arguing that the information was handed over initially on the understanding that it remain confidential. Mr Valukas’ report exposes concerns expressed by the OTS concerning Lehman’s liquidity. After Lehman acquired and financed the $23.6 billion buyout of Archstone-Smith Real Estate Investment Trust in May 2007, along with the property company Tishman Speyer, the OTS noted that Lehman exceeded its own risk appetite limits. It criticised Lehman for being "materially over-exposed to commercial property and for entering into the Archstone deal without sound risk management practices

14 Fun Facts About The U.S. Government's Massive Debt Problem

The U.S. government is currently creating one of the most colossal monuments in the history of the world. It is the U.S. national debt, and it threatens to literally destroy the American way of life. For decades now, this generation has been recklessly spending the money of future generations and has been convinced that they have been getting away with it. Americans have been enjoying an obscenely high standard of living, but the party is almost over and the day of reckoning is fast approaching.

It has been a great party, but it was fueled by the biggest mountain of debt in the history of the world. As many of us know, it can be extremely fun running up a huge credit card bill, but it can be even more painful to pay it off. Now our national "credit card bills" are starting to arrive and nobody really seems to know what to do. The U.S. national debt will forever be a lasting reminder of the greed and recklessness of this generation. The truth is that the United States is NOT the "richest and most powerful nation" in the world. Rather, we are a spoiled, bloated, greedy nation that has run up a debt so big that words simply do not do it justice.In fact, the U.S. national debt is so bizarre that it is hard to know whether to laugh about it or cry about it. For today at least, we will have some fun with it. The following are 14 fun facts about the U.S. government's massive debt problem....

#1) As of December 1st, 2009, the official debt of the United States government was approximately 12.1 trillion dollars.

#2) To pay this 12.1 trillion dollar debt would require approximately $40,000 from every single person living in the United States.

#3) Now the U.S. Congress has approved an increase in the U.S. government debt cap to 14.3 trillion dollars. to pay this increase off would require approximately $6,000 more from every man, woman and child in the United States.

#4) The U.S. government's debt ceiling has been raised six times since the beginning of 2006.

#5) So how hard is it to spend a trillion dollars? If you spent one dollar every second, you would have spent a million dollars in twelve days. At that same rate, it would take you 32 years to spend a billion dollars. But it would take you more than 31,000 years to spend a trillion dollars.

#6) When Ronald Reagan took office, the U.S. national debt was only about 1 trillion dollars.

#7) The U.S. national debt has more than doubled since the year 2000.

#8) Barack Obama’s most recently proposed budget anticipates $5.08 trillion in deficits over the next 5 years.

#9) The U.S. national debt on January 1st, 1791 was just $75 million dollars. Today, the U.S. national debt rises by that amount about once an hour.

#10) The U.S. national debt rises at an average of approximately $3.8 billion per day.

#11) In 2010, the U.S. government is projected to issue almost as much new debt as the rest of the governments of the world combined.

#12) The U.S. government has such a voracious appetite for debt that the rest of the world simply doesn't have enough money to lend us. So now the Federal Reserve is buying most U.S. debt, and the only reason they can do that is because they basically create the money to lend us out of thin air.

#13) A trillion $10 bills, if they were taped end to end, would wrap around the globe more than 380 times. That amount of money would still not be enough to pay off the U.S. national debt.

#14) As if all of the above was not bad enough, according to the 2008 Financial Report of the United States Government, which is an official United States government report, the total liabilities of the United States government, including future social security and medicare payments that the U.S. government is already committed to pay out, now exceed 65 TRILLION dollars.

Is China's Politburo spoiling for a showdown with America?

by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard