District National Bank, Dupont branch, Washington, DC

Ilargi: It's not that hard:

• The United Auto Workers spent $52 millon on Obama's campaign. Now they stand to lose at least $16 billion in pensions from General Motors and $7.1 billion from Chrysler. GM will still hand Rick Wagoner, fired by Obama, over $20 million in pensions. And GM has a relatively well-funded pension fund. The PBGC is supposed to take over a large chunk of the obligations, for which it will use taxpayer money. Sure.

• Pension plans for US state and municipal employees lost 30% of their value in 2008. In January and February of 2009, they lost another 9%, for an annualized loss of 54%. In dollars, the total loss adds up to about $1.2 trillion. The plans are some 50% underfunded, and all they can do is hold a firesale, at very low prices, of what assets they have left (and that still attract buyers).

• I'm admittedly a bit in the dark on the following, but I would bet that the vast majority of pension funds still base their long term views on annual returns of 7% or 8% on investments. Which they haven't gotten in 15 years, even in boom times. Now they are off their own marks by 50% or 60%.

It's not hard to see where this story ends. And the same is true for pension funds all over the world. There may of course be exceptions, and there will even be some in the US, but they'll be as rare as Hailey's comet. And don't get me started about all the funds that have been robbed blind by companies and governments.

How Can Mortgage Securities Be Worth So Little When Houses Aren't Going To Zero?

The study out of Harvard and Princeton arguing against the official story line about firesales underpricing toxic assets is now coming under fire from those who think the authors are too pessimistic about asset values. Megan McArdle at the Atlantic's Business blog raises two objections.Her first objection isn't really so much an argument as a lament. The correct response is simply: Yes. We are in big trouble. Some of our big money center banks are insolvent. But just because something is very bad news doesn't mean it isn't true. The second objection is more substantive. We hear a different version of it all the time: real estate isn't going to zero, so therefore securities backed by real estate can't go to zero. This makes sense only if you don't really understand how complex the collateralized debt market got during the boom years. Because once you understand this, it's pretty obvious that even though most mortgages will continue to perform, lots of real-estate based assets held by banks can go to zero.

- If toxic assets aren't underpriced, we're all in "big, big, BIG trouble."

- The market prices for toxic assets don't reflect reasonable expectations of cash flows.

How To Make An Asset Backed Security

Let's ilustrate this with an example of an asset backed security built on home loans. (We're borrowing the example from the excellent Acrued Interest blog.) These weren't exotic credit products. In fact, for most of the years building up to the crash, HEL ABS (as they were known in the business) was the dominant credit product. In 2005, something like $400 billion were issued. At the time, JP Morgan Chase was urging clients to buy this stuff by saying the pricing was "cheap" because of "irrational fears" over a housing bubble. So let's say our imaginary bank, CitiMorganAmerica, decides it wants to sell HEL ABS built from mortgages with $100 million face value. One of the first things it does is cut this up into tranches to reflect the risk and price points of various customers. For simplicities sake, we'll just pretend that there are only three tranches. (In reality, there could be dozens of tranches).The reason the lower tranches get bigger coupons is that they are riskier. They only receive interest payments after the tranche above them have received all interst payments they are due. Each tranche below senior receives principal payments only when the tranche above them has been full paid off. Any short fall hits the lowest level first. Here's where things start to get scary. If just 5% of the mortgages in that HEL ABS default, the subordinate tranche is worth zero. We're just about at 5% national default rate for all mortgages right now. Default rates on more recent mortgages are even higher. Fortunately, the ratings agencies were pretty good about this level of stuff so the Mezz and Sub investors knew they were getting riskier products, and only the senior deal would be rated AAA.

- Senior: 5.75% coupon, $80 million

- Mezzanine: 6.50% coupon, $15 million

- Subordinate: 8.00% coupon, $5 million

How To Make A CDO

Now lets see what happens when we build a CDO on these types of deals. CitiMorgan America takes $1 billion and buys the Mezz and Sub tranches of 50 HEL ABS deals that are built just like this. It slices up the CDO just like it did the earlier deal.These pay out just like the ABS, a waterfall filling up each bucket before anything gets paid to the next level down. The top tranche of this CDO can be rated AAA even though it is built out of already subordinated debt. You see, even though it is technically subordinated debt, there are so many underlying mortgages spread out across the country that the odds of systemic defaults materially affecting the cash flow would have been viewed very remote. After all, what are the odds that defaults will suddenly tick up all around the country?

- Senior: 5.45% coupon, $800 million

- Mezz: 6.00% coupon, $120 million

- Sub: 8.00% coupon, $40 million

- Equity: $40 million

How To Lose Your Shirt

See the problem? Here you have $1 billion of assets that can be devastated by a small increase in the default rate. If defaults climb to just 5% for the underlying mortgages, the cash flows will drop 25% as the portion of the CDO built from the Sub HEL ABS stops paying. Everything but the senior portion of the CDO gets wiped out. If the losses on the mortgages rise to just 10%--high defaults from those bubble years from 2005, lower than expected recovery rates from foreclosures on houses with falling values, cram downs--even the most senior piece will lose 30% of its value. In short, structured debt can rapidly decline in value even though the underlying assets don't decline as much. The benchmark index of the market for securities backed by home loans shows that the AAA tranches for deals made in 2007 are valued at about 23% of their original value. The lower tranches show losses greater than 97%. Some of this may no doubt reflect a bit of irrational fear and illiquidity. But claiming the overwhelming majority of these losses aren't real is just wishful thinking.

GM Pensions May Be 'Garbage' With $16 Billion at Risk

Den Black, a retired General Motors Corp. engineering executive, says he’s worried and angry. The government-supported automaker is going bankrupt, he says, and he’s sure some of his retirement pay will go down with it. "This is going to wreck us," said Black, 62, speaking of GM retirees. "These pledges from our companies are now garbage." As the biggest U.S. automaker teeters near bankruptcy, workers and retirees like Black are bracing for what may be $16 billion in pension losses if the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. has to take over the plans, according to the agency. As many as half of GM’s 670,000 pension-plan participants might see their benefits trimmed if that happened, an actuary familiar with the company’s retirement programs estimates. The possibility that GM might dump its pension obligations is likely to intensify debate over the treatment of executives of companies that receive U.S. aid. GM Chief Executive Officer Rick Wagoner, ousted by the Obama administration last month, may receive $20.2 million in pensions, according to a regulatory filing.

"The core issue is fairness," said Harley Shaiken, a labor professor at the University of California at Berkeley. "To have workers lose a significant amount of their pension after giving a lifetime to building a company is devastating under any circumstance. It’s made all the more worse by the symbolism of a $20 million payoff at the top." Measured by participants, GM’s pension plan would be the largest taken over by the PBGC, a quasi-government corporation created by Congress in 1974 to protect pension programs of bankrupt companies. Dealing with pensions may be one of the thorniest issues facing President Barack Obama in a GM bankruptcy. Unions including the United Auto Workers rallied behind his candidacy, spending $52 million to help elect him last year, according to Washington-based OpenSecrets.org, which tracks campaign spending.

In an election-night poll conducted by Peter D. Hart Research Associates, union members identified protecting pensions and Social Security and reducing health-care costs as their top goals for the new administration. "It’s going to be a very political decision," said John Casesa, who follows the auto industry as managing partner of Casesa Shapiro Group, a New York consulting firm. "I’m not really sure how this will go." GM’s pension system had a $20 billion shortfall as of Nov. 30, 2008, based on numbers the company provided the PBGC, said Jeffrey Speicher, a PBGC spokesman. By law, the agency would be able to make up only $4 billion of that, he said. "The rest would be lost," Speicher said in an interview. GM fell 9 cents, or 4.5 percent, to $1.91 at 1:05 p.m. in New York Stock Exchange composite trading and has dropped 38 percent this year through yesterday.

Current and future retirees of Chrysler LLC, the other U.S. automaker on life support, would forgo $7.1 billion, Speicher said. Chrysler’s plan is underfunded by $9.3 billion, and the agency would cover $2.2 billion, he said. Chrysler’s plan, with 250,000 members, would be the second- largest taken over by the PBGC. The biggest to date was the 120,000-member United Airlines plan, absorbed by the PBGC in 2005. The agency had an $11.2 billion deficit itself as of Dec. 31. The $16 billion that would be lost by GM workers and retirees is a "big deal," said Frank Todisco, senior pension fellow at the American Academy of Actuaries in Washington. "That’s a significant haircut on one’s benefits." The maximum amount that PBGC can pay retirees 65 or older is $54,000 a year. They would lose anything they get over that amount. Beneficiaries under 62 would be likely to lose a supplement of $15,000 to $18,000 paid by the GM plans to bring pensions up to $36,000 annually, according to the actuary with knowledge of the plans, who declined to be identified discussing potential cuts.

GM declined to disclose pension benefits or discuss what might happen to them should it file for bankruptcy. "We won’t speculate on the matter," said Renee Rashid- Merem, a spokeswoman for Detroit-based GM, which has received $13.4 billion in U.S. aid and asked for as much as $16.6 billion more. Obama on March 30 gave GM until June 1 to come up with deeper cuts in debt and labor costs than proposed by Wagoner to avert bankruptcy. He gave Chrysler until May 1 to form an alliance with Italy’s Fiat SpA. "Our goal, of course, is to do everything realistic to protect workers and their pensions," said White House spokesman Bill Burton. "We expect Chrysler’s pension plans to be nearly fully funded and have ample liquidity to continue benefit payments as required," said Michael Palese, a spokesman for the Auburn Hills, Michigan-based company.

Black, the former engineering executive, says he worked at GM for 34 years and for two years at Delphi Corp., the bankrupt auto-parts supplier formerly owned by the automaker. "If GM loses the pensions, it would mean 25 percent of my source of income would evaporate," said Black, who declined to say what his retirement pay is. "I would have to go back to work." Returning to work may not be an option for other GM retirees, Black said. "I’ve talked to lots of folks who would be devastated," he said. Not all companies that go bankrupt dump their pension obligations, said Speicher, the PBGC spokesman. Northwest Airlines Corp. emerged from bankruptcy in 2007 without terminating its plans, he said.

GM’s plan also is in relatively better shape than others, because it’s about 87 percent-funded, according to the actuary, compared with the typical pension plan’s 60 percent to 70 percent funding.

"The question of whether GM’s pension obligations are too great to allow it to operate effectively is a complicated one, and far from obvious," said Andrew Oringer, an employee- benefits lawyer at White & Case LLP in New York. "Nobody really knows" what would happen with GM pensions in a bankruptcy, said Jack Dickinson, president of an advocacy group for GM retirees called Over the Hill Car People. The "PBGC doesn’t want to touch it, they’ve got their own problems," said Dickinson, 65, who worked for 34 years in sales and management at GM. "We’re just hoping they take a hands-off approach. We depend on that money; we earned it, and it’s part of our compensation."

Investment losses hit public sector pensions

The crisis facing pension plans for US state and municipal employees is deepening as investment losses deplete the resources of retirement funds for teachers, police officers, firefighters and other local government workers. The largest state and municipal pension plans lost 9 per cent of their value of more than $2,000bn in the first two months of this year, according to data from Northern Trust. That followed a loss of 30 per cent in 2008, equal to about $900bn. Smaller funds, which underperform the larger ones, lost more, experts say. The losses have left retirement plans about 50 per cent funded - that is, they have only half the money needed to cover commitments to 22m current and former workers, experts say. State governments typically put the funding figures closer to 60-70 per cent, although most experts use different calculations.

"There is a massive national underfunding problem," said Orin Kramer, chairman of the New Jersey pension fund. Unlike company pension plans, state and municipal retirement funds have no federal guarantee fund. This has led to predictions of benefit cuts and possible federal intervention. "The federal government will get involved, without question," said Phillip Silitschanu, analyst at Aite Group, a consultancy. "They could provide federal loans, or demand cutbacks as a condition of stimulus money, or there could be a federalisation of some of these pensions." Without investment income, funds are liquidating assets at huge losses to pay pensions. Police pensions are in especially poor shape, in part because states have promised earlier retirement on full pensions, but seldom increased contributions.

Double blow for US pensions as values crash

The collapse in value of US state and local government pension plans is a disastrous double blow for them: they are being forced to sell off assets at huge discounts to pay out pensions, and are at the same time seeing their funding levels plummet to dangerous new lows. In the past year the funds, whose collective $2,000bn-plus in assets make them key investors in every asset class, have lost about 40 per cent of their value through investment losses. The 2,600 pension plans provide retirement savings for 22m public employees in towns and cities across the US, and range in size from the giant Calpers, with $120bn (€91bn, £81bn) in assets, to tiny small town funds which pay pensions for local garbage collectors and police.

Phillip Silitschanu, a senior analyst at Aite Group, a consultancy, says the pensions “could face a cash flow collapse, they are liquidating assets to meet their monthly cash flow needs instead of selling positions that are down 10 per cent, they are being forced to liquidate positions down 40 per cent. It is a firesale liquidation of assets to have the cash on hand to meet obligations”. Bill Atwood, the executive director of the Illinois State Board of Investments, says: “Right now it’s very bad. For the full year 2009 (ending in June) we will have $270m negative cash flow on $8.5bn in assets.” State pension benefits are protected by law, and must be paid even if the fund is making a loss. Calpers, the largest fund, has lost $70bn in value in the past eight months, but still has to pay $11bn in benefits this year. Unless the fund starts recouping its losses soon, the California state government, which is already mired in a huge deficit, will have to lift contributions to Calpers starting from next year.

Bad as the cashflow crisis is, the accompanying collapse in funding levels – an issue largely outside the control of the pension managers – is considered by most in the industry to be of greater significance. US pension plans are in generally worse shape than those in Europe. They were more underfunded, meaning they did not have the money to meet future pension commitments, even before the financial crisis hit, and their losses over the past year have been greater because they had larger allocations to equities. Funding has now fallen to about 50 per cent, according to industry estimates. Mr Silitschanu said: “As terrible a predicament that everyone thought these pension funds were in three or four years ago, they are much worse now.” Like several others, he believes some form of federal intervention is likely, possibly in the form of the state governments being forced to cut benefits in order to qualify for the money they receive as part of the economic stimulus package.

Hank Kim, the executive director of the National Conference on Public Employee Retirement Systems, the pension industry body, says: “I don’t think federal government involvement is a realistic possibility. “Public plan assets are down, but they are still in a very good financial situation. The issue is whether they have adequate cash flow to meet their obligations,” he argues. However, few others be-lieve the plans are in a good financial situation. Cutting benefits for new employees and raising the age of retirement are some previously unthinkable strategies being considered by state governments in an effort to contain the problem.

Merging weaker funds with others is another plan. Illinois’ five state retirement systems, which are collectively only about half funded, could be merged into one fund, as could those in Arkansas. Those less than 50 per cent funded include schemes in Philadelphia; West Virginia; Pittsburgh; Providence, Rhode Island; Little Rock, Arkansas; Jersey City, Wilmington, Delaware and Atlanta. Most experts believe that the situation is even worse than these official funding figures suggest, because of the way the funds calculate returns and liabilities. Almost all funds base their funding levels on an assumption of an annual return of 8 per cent, but in the decade to 2004 the average return was only 6.5 per cent. Successive state governments have expanded pension benefits, but often failed to lift contributions. No government has wanted to cut pensions.

Worldwide shipping rates set to tumble 74%

Global shipping rates are primed for a wrenching 74 per cent plunge in 2009 as commodity demand continues to fall in Asia and the massive glut of vessels ordered during the boom years finally hits the oceans. The expected collapse in rates, which could push dozens of shipowners close to bankruptcy, follows a 92 per cent decline in the Baltic Dry Index (BDI) of shipping rates over the course of last year. The misery is expected to continue well into 2010, with a further 15 per cent drop in rates before any rebound brings relief to fleet owners. The closely-watched gauge of world trade in iron ore, coal and other bulk cargoes has fallen for 19 straight days – the same ferocity of decline that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the catastrophic freezing of trade finance.

The stark warning of a continuing collapse in the BDI, issued today by analysts at Nomura Securities in Hong Kong, comes despite industry predictions of multiple order cancellations by shipowners and forecasts that record numbers of vessels may be put into storage. According to the gloomiest forecasts, fleet owners may lay-up the greatest number of ships since the oil crisis of the 1970s. But these measures, however drastic, may not be enough to fight further alarming declines in freight rates. Even if 40 per cent of worldwide order books are cancelled this year, the slump in global demand and the sharp rise in Chinese inventories of iron ore and coal, say analysts, suggest that the worst is yet to come. "We expect industry fundamentals [for bulk carriers] to deteriorate further as demand continues to remain weak and the large order book begins to be delivered," wrote Nomura’s Andrew Lee in a note to clients. On container shipping, the outlook is similarly miserable: "International routes are loss-making and are likely to remain so," he said.

Chinese imports of iron ore are falling because, despite Beijing's promise of massive infrastructure spending as part of the country’s vast $586 billion stimulus package, the pace of construction has slowed dramatically. Iron ore inventories loaded up along the docksides at Chinese ports are thought to have swollen by about eight million tons over the course of February, while the country’s exports of finished goods – the sort that used to fill container ships bound for the US and Europe – continue to fall. About 10 per cent of the world's 10,650 in-service container ships and bulk carriers are currently sitting empty and at anchor waiting for cargoes that are simply not emerging, said one London-based shipbroker. He added that as many as 500 ships of various types may be put into more permanent stasis to save their owners money as the recession runs its course. The waters off the coasts of Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines are expected to become the favoured parking lots for the world’s mothballed fleets.

To meet that impending demand, the world’s largest shipping services group, Inchcape, has launched a global lay-up service to ensure that any vessels put into hibernation are able to emerge in good working order. "The decision to lay-up a ship is not an easy one for a shipowner but we are giving the market what it needs right now," said Inchcape’s Narayanan Shankar in Singapore. Japan’s balance of payment figures, released yesterday by the country’s Ministry of Finance, provided yet another grim snapshot of the drop-off in world consumer demand and troubles facing the shipping industry. Exports and imports for the world’s second-biggest economy fell by about 50 per cent in February, with much of the decline due to the collapse in the once white-hot trade movement of components and half-finished goods around Asia.

Buffett & Berkshire: Downgraded By Their Own Kin

Berkshire Hathaway Inc. and its subsidiaries had already been on credit watch elsewhere, but there is a very interesting credit ratings downgrade that just took place. Moody’s has stripped Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway of its it Triple-A (Aaa) rating. The new rating is ‘Aa2.’ The National Indemnity Company was cut to ‘Aa1? from ‘Aaa.’ So why is this a more interesting downgrade? Berkshire Hathaway is actually the largest shareholder of Moody’s Corp.. S&P had already put the ratings on negative credit watch. Moody’s also cut the IFS ratings of other major insurance subsidiaries down to ‘Aa1? from ‘Aaa.’ Berkshire’s Prime-1 short-term issuer rating was affirmed. The good news is that the ratings outlook for all of these entities is stable. So at least no more downgrades are slated on the immediate horizon from Moody’s.

The reasons for the downgrade are a mere “ditto” to what was said elsewhere. Falling equity values, capital cushion reductions, and on. It also noted that National Indemnity’s regulatory capital fell 22% through 2008 to about $27.6 billion and by a further significant amount through early March 2009. Other insurance subsidiaries thrown under this bus are as follows:

• Berkshire Hathaway Assurance Corporation,

• Columbia Insurance Company,

• General Reinsurance Corporation,

• and Government Employees Insurance Company.

Moody’s did note that Berkshire and Buffett have several businesses that are mostly uncorrelated to the general economy which should continue to perform well. You can imagine the reaction Buffett had when he heard this, “Aw, Geez!”

Roubini Says Bank Takeovers Deepened Financial Market Crisis

Bank takeovers worsened the financial crisis by making firms that were already too big even bigger, said Nouriel Roubini, the New York University professor who predicted the financial crisis. "The institutions are insolvent," Roubini said in a Bloomberg Radio interview. "You have to take them over and you have to split them up into three or four national banks, rather than having a humongous monster that is too big to fail." JPMorgan Chase & Co. agreed to buy Bear Stearns Cos. in March 2008, with help from the Federal Reserve, while Bank of America Corp. purchased Merrill Lynch & Co. Wells Fargo & Co. took control of Wachovia Corp. and PNC Financial Services Group Inc. got National City Corp.

Banks around the world have reported $1.29 trillion in credit losses tied to the housing market collapse since 2007. The deficits, which spurred the first simultaneous recessions in the U.S., Europe and Japan since World War II, pushed the American government to pledge $12.8 trillion to stabilize the banking system and revive economic growth. That figure amounts to $42,105 for every man, woman and child in the country. The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, which tumbled 38 percent in 2008, has rallied 22 percent after sinking to a 12-year low on March 9. Roubini said in a Bloomberg interview that day that the S&P 500 is likely to drop to 600 or lower this year as the global recession intensifies.

US to delay bank test results for earnings

The U.S. Treasury Department is planning to delay the release of any completed bank stress test results until after the first-quarter earnings season to avoid complicating stock market reaction, a source familiar with Treasury's discussions said on Tuesday. The Treasury is still talking about how results of the regulatory stress tests on the 19 largest U.S. banks will be released, and may disclose them as summary results that are not institution-specific, the source said. The government is testing how the largest banks would fare under more adverse economic conditions than are expected in an attempt to assess the firms' capital needs. The tests are due to be completed by the end of April, but Treasury has said they may be finished before then.

The source, speaking anonymously because the Treasury has not made a final decision on what to disclose, said officials do not want any test results released before the earnings season wraps up for most U.S. banks on April 24. U.S. regulators have reached the closing phase of the stress tests, with many of the top banks having already turned in their internal versions of the test to officials. Bank of America Corp. Chief Executive Kenneth Lewis said last Thursday that his bank has already completed its test. Bank regulators are at the stage of reconciling their own versions of the results with the banks' internal assessments. Officials realize it may be hard to keep the results under wraps, and they are looking for ways the banks could disclose some details without unduly disturbing the markets. They are also looking at providing some summary information about how the banks fared.

There will be definitely be some information that will be provided at the end of it, but exactly what that will be, and when it will be provided, will come forth later," Comptroller of the Currency John Dugan, who supervises some of the nation's largest banks, said last week. The stress tests at the biggest banks are part of a wide-ranging effort to restore stability to a sector hit by huge mortgage-related losses. The tests are designed to determine the depth of banks' capital holes if conditions deteriorate further. After the tests are completed, the banks will have six months to either raise private capital to compensate, or accept government funds. But officials are worried about how the market will react to the stress test results if there is not a clear recovery path for a bank that is deemed to have a large capital need. The last thing Treasury wants to do is set off a panic, the source said.

Grim Earnings Draw Buyers to Treasurys

Treasurys ekeded out some gains Wednesday morning as concern about corporate earnings and the financial sector lifted demand for low-risk government debt. The bulk of the buying was seen overnight amid declines in Asian and European stocks after Alcoa Inc. reported a worse-than-forecast $497 million first-quarter loss. Bonds bounced off session highs in North American session as investors brace for a record $35 billion three-year Treasury note auction at 1 p.m. EDT. Traders said the movement in bond markets also reflected light trading this week due to the Passover, Good Friday and Easter holidays. The bond market will close early Thursday afternoon and will remain shut Friday. In recent trading, the two-year note's price was up 2/32 at 99 30/32 to yield 0.9%, while the 10-year note was up 6/32 at 98 27/32 to yield 2.89%. The 30-year bond was up 11/32 to 96 7/32 to yield 3.71%. Bond yields move inversely to prices.

Market participants noted that bond yields are likely to be capped within a narrow range as the bond market continues to be pushed around by two opposite forces. Rising supply puts upward pressure on bond yields but worries about banks, corporate earnings and weak stocks, coupled with the Federal Reserve's bond purchases, support bond prices and weigh down yields. "The market continues to try to find an equilibrium between two opposite forces here which will keep yields within the range," said Ralph Manigat, fixed-income analyst with 4Cast in New York. The 10-year note's yield has been kept between a range of 2.5% to 3% over the past few weeks, though the yield has bounced toward the upper band of the range over the past few sessions and headed toward 3%, a key psychological level for market participants. The Fed is scheduled to conduct a round of Treasury buying mid-morning Wednesday, targeting short-term maturities ranging from April 2010 to February 2011.

Since launching the buying on March 25, the Fed has bought $33.6 billion government securities. The central bank aims to buy up to $300 billion Treasurys over next six months as a way to lower mortgage rates and revive consumer and business lending. There is no major U.S. data release Wednesday. The Fed is set to release the minutes for its last monetary policy meeting last month when it decided to buy Treasurys as part of the so-called quantitative easing to aid credit markets and the economy. The minutes "at least should clarify the Fed's thinking" about the expansion of QE to include Treasuries after having distanced themselves from such an idea, said David Ader, head of U.S. government bond strategy at RBS Securities Inc in Greenwich, Connecticut. "We'd love to hear how they are determining what to buy -- little obvious logic heretofore -- but doubt that will be discussed in the minutes," said Mr. Ader. "In short, we may get more of an 'ah' than an 'ooh' to make the subtle distinction."

The three-year note auction is the second leg of the government's $59 billion note sales this week. The Treasury Department auctioned off $6 billion reopening of a 10-year Treasury inflation-protected security. The final leg of auction, an $18 billion reopening of the 10-year note, is scheduled Thursday. Richard Fisher, president of the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, said Wednesday the first "green shoots" of recovery can be seen in the U.S. economy as steps taken by the Federal Reserve Board and other U.S. authorities begin to take effect. Speaking on a panel in Tokyo sponsored by the Japan Center for Economic Research, the Institute for International Monetary Affairs and the Japanese Bankers Association, Fisher said no one can accuse the Fed of being slow to react to the crisis. It was the magnitude of authorities' activism, rather than the speed, that had unsettled some in the markets. "Whether those (steps) were sufficient or not, it's too early to tell," he said, but, he added, "we're beginning to see some healthy signs."

Fed minutes curb ‘green shoots’ hopes

The Federal Reserve sharply downgraded its economic outlook at its last meeting only three weeks ago, minutes released on Wednesday revealed, challenging the view that green shoots of recovery are now plain to see. While there has been more positive economic news since the March 18 meeting, the tenor of the Fed discussion suggests most policymakers will treat this data with some scepticism. “Most participants viewed downside risks as predominating in the near term,” the minutes say. Officials worried about “adverse feedback effects as reduced employment and production weighed on consumer spending” and a “weakening economy boosted the prospective losses of financial institutions, leading to a further tightening of credit conditions.”

The downgrade to the forecast led the Fed to announce that it would dramatically increase its purchases of assets and start buying Treasuries for the first time in the hope that this would support growth, the minutes show. They also reveal considerable disagreement within the Fed as to how robust an eventual recovery is likely to be. Some officials “believed that the natural resilience of market forces would become evident later this year.” But others “saw recovery as delayed and weak.” Some worried that the crisis would ultimately lead to a reduction in the potential growth rate of the US economy.

Meanwhile minutes of an earlier February 7 meeting – at which Fed policymakers discussed plans to extend financing to toxic legacy assets as part of the government’s financial rescue plan – show a number of Fed officials were concerned that the move could expose the Fed to credit losses. “The staff’s projections for real GDP in the second half of 2009 and 2010 were revised down,” the minutes say. The Fed staff no longer expected growth to recover later this year, and instead forecast that output would “flatten out gradually” in the second half and then “expand slowly next year.”

Fed policymakers agreed with the staff analysis. “Nearly all meeting participants said that conditions had deteriorated relative to their expectations,” the minutes say. Several worried that inflation “was likely to persist below desirable levels” – although they did not specifically refer to the danger of deflation, or falling prices. Fed officials expressed concern about the “degree and pervasiveness of the decline in foreign economic activity” since their last meeting in January, which threatened US exports. As of March 18 the US central bank appeared highly sceptical of the notion that some positive surprises in the US data added up to evidence that a recovery was in the making. “Participants did not interpret the uptick in housing starts in February as the beginning of a new trend,” the minutes say. While some thought starts could not have too much further to fall, Fed officials reasoned that the overhang of unsold homes would continue to weigh on residential investment.

Several policymakers “noted the tentative signs of stabilisation in consumer spending in January and February.” But “others suggested that strains on household balance sheets from falling equity and house prices, reduced credit availability and the fear of unemployment could well lead to further increases in the savings rate that would damp consumption growth.” While businesses were liquidating excess inventories, ratios of inventories to sales remained high, Fed officials observed. “Against this backdrop participants anticipated further employment cutbacks over coming months, though perhaps at a gradually diminishing rate.” Fed officials debated whether to focus their additional stimulus on Treasuries or mortgage-backed securities, but ultimately opted to do both, in part as a portfolio strategy given the uncertainty as to how much impact either operation would have on the economy. Without specifying any target for an increased money supply, Fed policymakers “agreed that the monetary base was likely to grow significantly as a consequence of additional asset purchases.”

California's anti-tax crusaders talk revolt

Taking inspiration from a landmark 1970s tax revolt, a determined group of activists say the moment is right for another voter uprising in California, where recession-battered residents have been hit with the highest income and sales tax rates in the nation. And like Proposition 13, the 1978 ballot measure that transformed the state's political landscape and ignited tax-reform movements nationwide, they see the next backlash coming not from either major political party, but from the people. If the anti-tax crusaders can galvanize voter discontent, they hope to roll back the latest tax hikes, impose permanent, iron-clad spending caps on Sacramento lawmakers and make the issue central in the 2010 gubernatorial election.

"There's a lot of latent anger boiling to the surface out there," said Jon Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, a group named after the California anti-tax crusader who spearheaded Prop 13. An angry mob of thousands converged on an Orange County parking lot in southern California on a recent Saturday morning for an anti-tax protest, stunning even the organizers with the size of the turnout. It was just one in a series of public demonstrations that have cropped up around the state. Talk of a brewing tax revolt has been largely ignored by the mainstream media, and many political analysts are skeptical, though they concede that the taxpayer mutiny that led to the landmark Prop 13 was similarly dismissed by political professionals. That referendum passed in a landslide despite furious opposition from the political establishment -- and highlighted the possibilities for grassroots campaigners to enact measures with ballot initiatives and bypass the legislature. It slashed property tax rates by 57 percent, capped future collections and required any new tax hikes to be approved by a two-thirds majority in both houses of the state legislature.

"There's no way to predict whether we're going to see a reprise of the revolt that led to Prop 13 or whether this is a false start," said Dan Schnur, director of the Jesse Unruh Institute of Politics at USC and a onetime adviser to presidential candidate Sen. John McCain. "But the economic conditions are ripe for tax revolt, and advances in technology certainly make it easier to organize a coalition without access to huge amounts of money." Those conditions include a heavy tax burden that is growing heavier plus a worsening economy. California already had the highest income tax rates of any state in the country when the legislature raised them in February to help close a $42 billion deficit that also required deep spending cuts and additional borrowing.

The state's top income tax rate is now 10.425 percent, which is 1.5 percentage points higher than second-place Rhode Island and rises to 10.55 percent if certain economic triggers are hit. Most U.S. states have a top rate of less than 7 percent, and seven collect no income tax at all. California lawmakers also boosted the state's sales tax to 8.25 percent, nearly doubled the vehicle license fee and sharply reduced the tax credit for dependents. Though Prop 13 has become sacrosanct in California politics, it has its critics, who blame it for forcing the state to rely too heavily on sales and income taxes and limiting a critical funding source for public schools. The state, which was hard hit by the subprime mortgage crisis, faces sharply declining revenues and an unemployment rate over 10 percent.

"I certainly don't want my taxes raised but one thing I do recognize is that we are in the middle of a financial meltdown," California Assembly Speaker Karen Bass, a Democrat, told Reuters in an interview. "We have a constitutional obligation to balance the budget so we had no choice" but to raise taxes, Bass said. "Unfortunately when you fan the flames you can lead to things like a revolt but I'm certainly hoping it doesn't deteriorate to that." Analysts also say the anti-tax revolutionaries would be met with fierce opposition from California's public employee unions, a powerful political force with considerably more money and unmatched influence over the Democrat-led legislature. But the activists are undaunted by doubters within the establishment.

"Every chamber of commerce, every editorial board, every labor group, every tax-receiver group, everybody opposed Prop 13 except the voters," Coupal told Reuters. "That reflects a massive disconnect between the real people and the political elite, and that disconnect is right now as great as I've ever seen it." The first test of anti-tax crusaders' influence could come in a May 19 special election with voting on Proposition 1A, which is backed by California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and Democratic leaders and would extend the tax increases in exchange for a new cap on spending. At the Orange County anti-tax rally, sponsored by two radio talk show hosts, voters' resentment erupted as they chanted slogans, waved placards and demanded action in the state capital Sacramento. "There was a huge amount of anger," said John Kobylt, talk show host on KFI-AM 640. "It was visceral. You could feel it. You could almost touch it. It was almost frightening to be out there. It was a tremendous expression of hatred over what's going on."

What the G2 must discuss now the G20 is over

by Martin Wolf

Did the meeting of the Group of 20 in London last week put the world economy on the path of sustainable recovery? The answer is no. Such meetings cannot resolve fundamental disagreements over what has gone wrong and how to put it right. As a result, the world is on a path towards an unsustainable recovery, as I argued last week. An unsustainable recovery might be better than none, but it is not good enough. This summit had two achievements: one broad and one specific. First, "to jaw-jaw is better than war-war", as Winston Churchill remarked. Given the intensity of the anger and fear loose upon the world, discussion itself must be good. Second, the G20 decided to treble resources available to the International Monetary Fund, to $750bn, and to support a $250bn allocation of special drawing rights (SDRs) – the IMF’s reserve asset. If implemented, these decisions should help the worst-hit emerging economies through the crisis. They also mark a return to a big debate: the workings of the international monetary system.

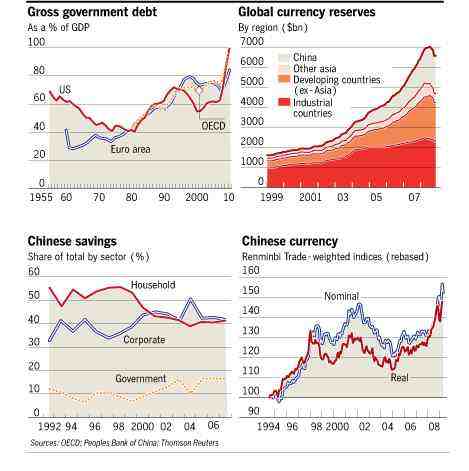

This is the point at which the eyes of countless readers will glaze over. It is easier for most to believe that the explanation for the crisis is solely the deregulation and misregulation of the financial systems of the US, UK and a few other countries. Yet, given the scale of the world’s macroeconomic imbalances, it is far from obvious that higher regulatory standards alone would have saved the world. This is not just a matter of historical interest. It is also relevant to the sustainability of the recovery. Fiscal deficits are now generally far bigger in countries with structural current account deficits than in those with current account surpluses. This is because the latter can import a substantial part of the stimulus introduced by the former. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development forecasts a jump in US public debt of almost 40 per cent of gross domestic product over three years (see chart). It is quite likely, therefore, that the next crisis will be triggered by what markets see as excessive fiscal debt in countries with large structural current account deficits, notably the US. If so, that could prove a critical moment for the international economic system.

Intriguingly, the country raising these big questions is China. This is, no doubt, for self-serving reasons: China is worried about the value of its foreign currency reserves, most of which are denominated in US dollars; it wants to relieve itself of blame for the crisis; it wishes to preserve as much of its development model as possible; and it is, I suspect, seeking to countervail US pressure on the exchange rate of the renminbi. Wen Jiabao, the Chinese prime minister, has noted his country’s concern over the value of its vast reserves. At close to $2,000bn, these are almost half of 2008 GDP. Imagine what Americans would say if their government had invested about $7,000bn (the equivalent relative to US GDP) in the liabilities of not altogether friendly governments. The Chinese government is beginning to realise its mistake – too late, alas. Meanwhile, Governor Zhou Xiaochuan of the People’s Bank of China has produced a remarkable series of speeches and papers on the global financial system, global imbalances and reform of the international monetary system. These are both a statement of the Chinese point of view and a contribution to global debate. One may not agree with all he is saying. Yet the fact that he is speaking out is itself significant.

Governor Zhou argues that the high savings rate of China and other east Asian countries is a reflection of tradition, culture, family structure, demography and the stage of economic development. Furthermore, he adds, they "cannot be adjusted simply by changing the nominal exchange rate". In addition, he insists, "the high savings ratio and large foreign reserves in the east Asian countries are a result of defensive reactions against predatory speculation", particularly during the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98. None of this can be changed swiftly, insists the governor: "Although the US cannot sustain the growth pattern of high consumption and low savings, it is not the right time to raise its saving ratio at this very moment." In other words, give us US frugality, but not yet. Meanwhile, adds the governor, the Chinese government has produced one of the largest stimulus programmes in the world. Moreover, the vast accumulations of foreign currency reserves, up by $5,400bn between January 1999 and their peak in July 2008 (see chart), reflect the emerging economies’ demand for safety. But since the US dollar is the world’s main reserve asset, the world depends on US monetary emissions. Moreover, the US tends to run current account deficits, for this reason. The result has been a re-emergence of a weakness discussed in the twilight years of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, which broke down in the early 1970s: over-issuance of the key currency. The long-term answer, he adds, is a "super-sovereign reserve currency".

It is easy to object to many of these arguments. Much of the extraordinary increase in China’s aggregate savings is the result of rising corporate profits (see chart). It would surely be possible to tax and then spend a part of these huge corporate savings. The government could also borrow more: at the 3.6 per cent of GDP forecast by the IMF this year, its deficit remains decidedly modest. It is also hard to believe that a country such as China should be saving half of its GDP or running current account surpluses of close to 10 per cent of GDP. Similarly, while the international monetary system is indeed defective, this is hardly the sole reason for the world’s vast accumulations of foreign currency reserves. Another is over-reliance on export-led growth. Nevertheless, Governor Zhou is correct that part of the long-term solution of the crisis is a system of reserve creation which allows emerging economies to run current account deficits safely. Issuance of SDRs is a way of achieving this goal, without changing the fundamental character of the global system. China is seeking to engage the US. That is itself enormously important. However self-seeking its motivation, that is a necessary condition for serious discussion of global reforms. Yet China must also understand an essential point: the world cannot safely absorb the current account surpluses it is likely to generate under its current development path. A country as large as China cannot hope to rely on such large current account surpluses as a source of demand. Spending at home must still rise sharply and sustainably, relative to growth of potential output. It is as simple – and difficult – as that.

US student debt and defaults surge

When Robert Applebaum graduated from Fordham Law in 1998, he took the public-interest job near to his heart: assistant district attorney in Brooklyn, N.Y., at a salary of $36,000 – despite law-school debt of $75,000. He took five years of forbearance on the loan. Bad move. Mr. Applebaum’s indebtedness today stands at $96,000, even though he fled the job he loved for the higher-paying private sector in 2003. "It’s like having a mortgage, but without the house," he says of monthly payments just under $500. At that rate, the debt won’t be fully paid for two decades. Student debt in the United States has surged in recent decades, with outstanding federal student debt now topping $500 billion. The share of young adults carrying some educational debt has almost tripled since 1983, according to economist Ngina Chiteji.

At the same time, defaults are on the rise. Between 2006 and 2007, the proportion of borrowers who were supposed to enter repayment for the first time and who instead defaulted went up – from 5.2 percent to 6.9 percent, according to a Department of Education report last month. That percentage is the highest in more than a decade. And the 2008 and 2009 default rates are likely to be much higher. Some help is on the way. Sallie Mae, America’s largest lender to college students, announced last month a loan type that students start paying while still in college. The early jump on interest payments means that balances can be paid off an average of nine years earlier, with a savings of 40 percent over the life of the loan, the company says. Some provisions of a 2007 education law set to take effect this summer will also reduce interest rates on some federal loans and place others on income-based repayment plans.

President Obama’s budget, meanwhile, proposes to expand federal loan programs and tax breaks. Applebaum and others, however, are pushing the government to go further, advocating student debt forgiveness. But they face an uphill climb. Historically, Washington hasn’t taken up their cause, and many economists don’t see it their way, either. "I’m sure that all people wish they did not have to borrow to go to college," says Dr. Chiteji of Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., who has studied indebtedness among the young. "We’d all like the things we want to be free to us…. [But] the costs of college have to be borne by someone in society, and there’s a strong economic argument for having that ‘someone’ be the student."

Most young-adult debt profiles haven’t yet reached horror-story status. In fact, young people’s overall indebtedness as a proportion of income has not changed much since the 1960s, according to Chiteji’s research. There is an important difference between then and now, though. Mortgage debt used to be virtually the only major debt held by young people. Now, their debt load is much heavier on schooling. And student debt can be extremely difficult to discharge, even in bankruptcy court. That’s partly because of a crackdown on defaults following a record default rate of 22.4 percent during the 1990-91 recession. The difficulty of discharging student loans is one reason that Applebaum has launched his efforts. If student debt is forgiven, he argues, the economy will be stimulated. That would free a great many people to buy homes and cars, he says. Applebaum is building a student-debt advocacy organization, and in January, he started the Facebook group "Cancel Student Debt to Stimulate the Economy," which has mushroomed to 160,000 members as of early April.

Now, more than a few members of Applebaum’s Facebook group are wrestling with the question: How much is a good education – especially a private, liberal-arts education – really worth? In 2004, Brian Kraus graduated from Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa, with a double major in business and economics and sports management – and with $50,000 of mostly private student debt. Now, he’s a customer-support manager at a Denver telecommunications firm, and he’s making monthly loan payments of just over $500. In a few years, on his payment plan, he expects the amount he owes each month to rise near $1,000. "I signed for [the loans] and I believe in paying them, and I will do so until I can’t do it anymore," says Mr. Kraus. He realizes that, in a tough economy, many won’t sympathize. But, he says, "If our debts were paid – and I do believe they need to be paid rather than just forgiven, or else we are causing more issues for the loan companies – then think about the amount of money that could be directly infused into the economy."

AIG aircraft unit seeks $5 billion Fed credit line

AIG’s aircraft-leasing unit is in talks over a $5bn credit line from the Federal Reserve that could be used to facilitate its sale – an unusual move that would raise the stakes in the US government’s bail-out of the stricken insurer. People close to the situation said discussions between International Lease Finance Corp, AIG and the New York Fed were still ongoing and no decision on whether the facility would be provided, and how big it would be, had yet been taken. ILFC, a profitable company and a top customer to both Boeing and Airbus, is in advanced talks with three private equity consortia but it needs extra liquidity because AIG’s collapse has choked off many of its traditional sources of funds.

A bitter downturn in demand for air travel has made the task of raising extra funding even more daunting. People close to the situation said the credit line from the Fed would come from the billions of dollars worth of loans the monetary authorities have already extended to AIG. But even if ILFC’s credit facility comes from existing resources, the Fed’s involvement in the sale of an AIG subsidiary could deepen criticism of the authorities’ role in the insurer’s rescue. The New York Fed declined to comment. AIG, with the Fed’s blessing, has pledged to support ILFC until its separation from the insurer.

But the company’s efforts to raise several billion dollars through a new credit facility have met with tepid demand from European banks and other traditional sources of aviation finance, people familiar with the matter said. AIG said ILFC’s fundraising efforts were "making normal progress given the tough market conditions", and declined to comment further. ILFC is in advanced talks with several consortia of potential buyers that include Carlyle Group, Thomas H. Lee Partners and Greenbriar Equity Group. But without reassurances that ILFC’s short-term financing needs could be met, it may be unlikely any of the bidders would be willing to take on such a capital-intensive business. ILFC has ordered 168 new aircraft worth $16.7bn from Boeing and Airbus. The aeroplanes are scheduled to be bought during the next 10 years, with 49 of them – worth about $3bn – set to be delivered this year.

GM Meeting With Treasury Team on Deeper Cost Cuts

General Motors Corp., facing a potential June 1 bankruptcy without new debt cuts, is meeting this week and next with a team from the U.S. Treasury to craft a revised plan to save the company. The meetings are led for the Treasury by Harry J. Wilson, a former partner in Silver Point Capital LP, and about 14 other people including advisers from Boston Consulting Group and Rothschild Group, said Josh Earnest, a White House deputy press secretary. GM and the department’s team will work to speed existing cuts and identify new savings, Earnest said today. "It underscores that they are trying to find an alternative to bankruptcy even if that’s difficult to achieve," said John Casesa, managing partner of Casesa Shapiro Group in New York and former auto analyst at Merrill Lynch. "It’s a sign of the sincerity of the process, at least."

GM Chief Executive Officer Fritz Henderson, who took over last week after President Barack Obama asked Rick Wagoner to step down as CEO and chairman, has said he’s racing to get an agreement with bondholders, unions and others to avoid a government-ordered bankruptcy. If he can’t reach an accord, GM has said it will accept a U.S.-led filing for court protection. The Obama group also includes Xavier Mosquet, senior partner and managing director of Boston Consulting’s Detroit office, and people from fields such as fashion who are studying alternative ways for GM to run its business, said a person briefed on the meetings. A Boston Consulting spokesman confirmed its role in the gatherings and wouldn’t discuss details. "GM and the task force remain engaged in discussions relative to GM’s restructuring actions, but we won’t comment on specific meetings or details of the ongoing discussions," said Renee Rashid-Merem, a spokeswoman for the Detroit-based company.

GM fell 7 cents, or 3.5 percent, to $1.93 at 4:15 p.m. in New York Stock Exchange composite trading. The shares have declined 40 percent this year. Susan Docherty, GM vice president for Buick, Pontiac and GMC in North America, said in an interview at the New York auto show that executives at her level are getting "really good, thoughtful questions" daily from the Treasury team as they try to understand the company’s operations. The automaker also is speeding up preparations for a possible bankruptcy filing even as directors and executives try to avoid that, people familiar with the plans said two days ago. GM would focus on forming a new company from its best assets if court protection is needed, the people said. Efforts to set a new cost-cut goal center on how to go beyond a proposal to slash debt by 46 percent and shed 47,000 jobs in 2009, the people said.

The moves are a response to Obama’s March 30 rejection of GM’s plan for keeping $13.4 billion in federal loans. With bondholders and the United Auto Workers balking at concessions, a push for more savings makes bankruptcy more "probable," Henderson said. GM’s board met April 4 and April 5, and more discussions are planned inside the company and with the Obama administration after the biggest U.S. automaker was given 60 days to revamp itself without a specific savings target, the people said. The meetings today are part of those plans. Preparations for a court filing were ratcheted up in February as a precaution against a defeat for GM’s bid to keep its U.S. loans, the people said. GM said it prefers to restructure outside bankruptcy court. The company has had losses of $82 billion since 2004.

The preparations include looking at a so-called 363 sale, a reference to a section of the Chapter 11 bankruptcy code that would help create a new automaker from the assets and brands of GM, boosting the company’s survival chances, the people said. GM has $62 billion in debt, and its Feb. 17 presentation to Treasury envisioned shrinking that sum to $33.5 billion by trimming obligations to a union-retiree health fund and getting bondholders to accept less in an equity swap. Until new savings requirements are set, substantive talks with the UAW and bondholders may be delayed, the people said. "There’s a lot at stake here, not just economically but politically," Casesa said. "Politically, they would probably like to avoid a bankruptcy."

The IMF Rules the World

by Michael Hudson

Not much substantive news was expected to come out of the G-20 meetings that ended on April 2 in London – certainly no good news was even suggested. Europe, China and the United States had too deeply distinct interests. American diplomats wanted to lock foreign countries into further dependency on paper dollars. The rest of the world sought a way to avoid giving up real output and ownership of their resources and enterprises for yet more hot-potato dollars. In such cases one expects a parade of smiling faces and statements of mutual respect for each others’ position – so much respect that they have agreed to set up a "study group" or two to kick the diplomatic ball down the road.

The least irrelevant news was not good at all: The attendees agreed to quadruple IMF funding to $1 trillion. Anything that bolsters IMF authority cannot be good for countries forced to submit to its austerity plans. They are designed to squeeze out more money to pay the world’s most predatory creditors. So in practice this G-20 agreement means that the world’s leading governments are responding to today’s financial crisis with "planned shrinkage" for debtors – a 10 per cent cut in wage payments in hapless Latvia, Hungary put on rations, and permanent debt peonage for Iceland for starters. This is quite a contrast with the United States, which is responding to the downturn with a giant Keynesian deficit spending program, despite its glaringly unpayable $4 trillion debt to foreign central banks.

So the international financial system’s double standard remains alive and kicking – at least, kicking countries that are down or are falling. Debtor countries must borrow a trillion from the IMF not to revive their own faltering economies, not to pursue counter-cyclical policies to restore market demand (that is only for creditor nations), but to pass on the IMF "aid" to the poisonous banks that have made the irresponsible toxic loans. (If these are toxic, who put in the toxin? To claim that it was all the "natural" workings of the marketplace is to say that free markets curdle and sicken. Is this what is happening?)

In Ukraine, a physical fight broke out in Parliament when the Party of Regions blocked an agreement with the IMF calling for government budget cutbacks. And rightly so! The IMF’s operating philosophy is the destructive (indeed, toxic) belief that imposing a deeper depression with more unemployment will reduce wage levels and living standards by enough to pay debts already at unsustainable levels, thanks to the kleptocracy’s tax "avoidance" and capital flight. The IMF trillion-dollar bailout is actually for these large international banks, so that they will be able to take their money and run. The problem is all being blamed on labor. That is the neo-Malthusian spirit of today’s neoliberalism.

The main beneficiaries of IMF lending to Latvia, for example, have been the Swedish banks that have spent the last decade funding that country’s real estate bubble while doing nothing to help develop an industrial potential. Latvia has paid for its imports by exporting its male labor of prime working age, acting as a vehicle for Russian capital flight – and borrowing mortgage purchase-money in foreign currency. To pay these debts rather than default, Latvia will have to lower wages in its public sector by 10 per cent -- and this with an economy already depressed and that the government expects to shrink by 12 percent this year!

To save the banks from losing on their toxic mortgages, the IMF is bailing them out, and directing the Latvian government to squeeze labor all the more – and to charge for education rather than providing it freely. The idea is for families to take a lifetime of debt not only to live inside rather than on the sidewalk, but to get an education. Alcoholism rates are rising, as they did in Russia under similar circumstances in Yeltsin’s "Harvard Boys" kleptocracy after 1996.

The insolvency problem of the post-Soviet economies is not entirely the IMF’s fault, to be sure. The European Community deserves a great deal of blame. Instead of viewing the post-Soviet economies as wards to be brought up to speed with Western Europe, the last thing the EU wanted was to develop potential rivals. It wanted customers – not only for its exports, but most of all for its loans. The Baltic States passed into the Scandinavian sphere, while Austrian banks carved out financial spheres of influence in Hungary (and lost their shirt on real estate loans, much as the Habsburgs and Rothschilds did in times past). Iceland was neoliberalized, largely in ripoffs organized by German banks and British financial sharpies.

In fact, Iceland ( where I’m writing these lines) looks like a controlled experiment – a very cruel one – as to how deeply an economy can be "financialized" and how long its population will submit voluntarily to predatory financial behavior. If the attack were military, it would spur a more alert response. The trick is to keep the population from understanding the financial dynamics at work and the underlying fraudulent character of the debts with which it has been saddled – with the complicit aid of its own local oligarchy.

In today’s world, the easiest way to obtain wealth by old-fashioned "primitive accumulation" is by financial manipulation. This is the essence of the Washington Consensus that the G-20 support, using the IMF in its usual role as enforcer. The G-20’s announcement continues the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve bank bailout over the past half-year. In a nutshell, the solution to a debt crisis is to be yet more debt. If debtors can’t pay out of what they are able to earn, lend them enough to keep current on their carrying charges. Collateralize this with their property, their public domain, their political autonomy – their democracy itself. The aim is to keep the debt overhead in place. This can be done only by keeping the volume of debts growing exponentially as they accrue interest, which is added onto the loan. This is the "magic of compound interest." It is what turns entire economies into Ponzi schemes (or Madoff schemes as they are now called).

This is "equilibrium", neoliberal style. In addition to paying an exorbitant basic interest rate, homeowners must pay a special 18 per cent indexation charge on their debts to reflect the inflation rate (the consumer price index) so that creditors will not lose the purchasing power over consumer goods. Labor’s wages are not indexed, so defaults are spreading and the country is being torn apart with bankruptcy, causing the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. The IMF approves, announcing that it can find no reason why homeowners cannot bear this burden!

Meanwhile, democracy is being torn apart by a financial oligarchy, whose interests have become increasingly cosmopolitan, looking at the economy as prey to be looted. A new term is emerging: "codfish republic" (known further south as banana republics). Many of Iceland’s billionaires these days are choosing to join their Russian counterparts living in London – and the Russian gangsters are reciprocating by visiting Iceland even in the dead of winter, ostensibly merely to enjoy its warm volcanic Blue Lagoon, or so the press is told.

The alternative is for debtor countries to suffer the same kind of economic sanctions as Iran, Cuba and pre-invasion Iraq. Perhaps soon there will be enough such economies to establish a common trading area among themselves, possibly along with Venezuela, Colombia and Brazil. But as far as the G-20 is concerned, aid to Iceland and "doing the right thing" is simply a bargaining chip in the international diplomatic game. Russia offered $4 billion aid to Iceland, but retracted it – presumably when Britain gave it a plum as a tradeoff.

The IMF’s $1 trillion won’t help the post-Soviet and Third World debtor countries pay their foreign debts, especially their real estate mortgages denominated in foreign currency. This practice has violated the First Law of national fiscal prudence: Only permit debts to be taken on that are in the same currency as the income that is expected to be earned to pay them off. If central bankers really sought to protect currency stability, they would insist on this rule. Instead, they act as shills for the international banks, as disloyal to the actual economic welfare of their countries as expatriate oligarchs.

If you are going to recommend more of this consensus, then the only way to sell it is to do what British Prime Minister Gordon Brown did at the meetings: announce that "The Washington Consensus is dead." (He might have saved matters by saying "deadly," but used the adjective instead of the adverb.) But the G-20’s IMF bailout belies this claim. As Turkey was closing out its loan last year, the IMF faced a world with no customers. Nobody wanted to submit to its destructive "conditionalities," anti-labor policies designed to shrink the domestic market in the false assumption that this "frees" more output for export rather than being consumed at home. In reality, the effect of austerity is to discourage domestic investment, and hence employment. Economies submitting to the IMF’s "Washington Consensus" become more and more dependent on their foreign creditors and suppliers.

The United States and Britain would never follow such conditionalities. That is why the United States has not permitted an IMF advisory team to write up its prescription for U.S. "stability." The Washington Consensus is only for export. ("Do as we say, not as we do.") Mr. Obama’s stimulus program is Keynesian, not an austerity plan, despite the fact that the United States is the world’s largest debtor.

Here’s why the situation is unsustainable. What has enabled the Baltics and other post-Soviet countries to cover the foreign-exchange costs of their trade dependency and capital flight has been their real estate bubble. The neoliberal idea of financial "equilibrium" has been to watch "market forces" shorten lifespans, demolish what industrial potential they had, increase emigration and disease, and run up an enormous foreign debt with no visible way of earning the money to pay it off. This real estate bubble credit was extractive and parasitic, not productive. Yet the World Bank applauds the Baltics as a success story, ranking them near the top of nations in terms of "ease of doing business."

One practical fact trumps all the junk economics at work from the IMF and G-20: Debts that can’t be paid, won’t be. Adam Smith observed in The Wealth of Nations that no government in history had ever repaid its national debt. Today, the same may be said of the public sector as well. This poses a problem of just how these debtor countries are not going to pay their foreign and domestic debts. How will they frame and politicize their non-payment?

Creditors know that these debts can’t be paid. (I say this as former balance-of-payments analyst of Third World debt for nearly fifty years, from Chase Manhattan in the 1960s through the United Nations Institute for Training and Research [UNITAR] in the 1970s, to Scudder Stevens & Clark in 1990, where I started the first Third World sovereign debt fund.) From the creditor’s vantage point, knowing that the Great Neoliberal Bubble is over, the trick is to deter debtor countries from acting to resolve its collapse in a way that benefits themselves. The aim is to take as much as possible – and to get the IMF and central banks to bail out the poisonous banks that have loaded these countries down with toxic debt. Grab what you can while the grabbing is good. And demand that debtors do what Latin American and other third World countries have been doing since the 1980s: sell off their public domain and public enterprises at distress prices. That way, the international banks not only will get paid, they will get new business lending to the buyers of the assets being privatized – on the usual highly debt-leveraged terms!

The preferred tactic do deter debtor countries from acting in their self-interest is to pound on the old morality, "A debt is a debt, and must be paid." That is what Herbert Hoover said of the Inter-Ally debts owed by Britain, France and other allies of the United States in World War I. These debts led to the Great Depression. "We loaned them the money, didn’t we?" he said curtly.

Let’s look more closely at the moral argument. Living in New York, I find an excellent model in that state’s Law of Fraudulent Conveyance. Enacted when the state was still a colony, it was enacted in response British speculators making loans to upstate farmers, and demanding payment just before the harvest was in, when the debtors could not pay. The sharpies then foreclosed, getting the land on the cheap. So New York’s Fraudulent Conveyance law responded by establishing the legal principle that if a creditor makes a loan without having a clear and reasonable understanding of how the debtor can repay the money in the normal course of doing business, the loan is deemed to be predatory and therefore null and void.

Just like the post-Soviet economies, Iceland was sold a neoliberal bill of goods: a self-destructive Junk Economics. Just how moral a responsibility – and perhaps even more important, how large a legal liability –should fall on the IMF and World Bank, the U.S. Treasury and Bank of England whose economies and banks benefited from this toxic Washington Consensus junk economics? For me, the moral principle is that no country should be subjected to debt peonage. That is the opposite of democratic self-determination, after all – and of Enlightenment moral philosophy that economic policies should encourage economic growth, not shrinkage. They should promote greater economic equality, not polarization between wealthy creditors and impoverished debtors.

At issue is just what a "free market" is. It’s supposed to be one of choice. Indebted countries lose discretionary choice over their economic future. Their economic surplus is pledged abroad as financial tribute. Without the overhead costs of a military occupation, they are relinquishing their policy making from democratically elected political representatives to bureaucratic financial managers, often foreign – the new Central Planners in today’s neoliberal world. The best they can do, knowing the game is over, is to hope that the other side doesn’t realize it – and to do everything you can to confuse debtor countries while extracting as much as they can as fast as they can.

Will the trick work? Maybe not. While the G-20 meetings were taking place, Korea was refusing to let itself be victimized by the junk derivatives contracts that foreign banks sold. Korea is claiming that bankers have a fiduciary responsibility to their customers to recommend loans that help them, not strip them of money. There is a tacit understanding (one that the financial sector spends millions of dollars in public relations efforts to undermine) that banking is a public utility. It is supposed to be a handmaiden to growth – industrial and agricultural growth and self-sufficiency – not predatory, extractive and hence anti-social. So Korean victims of junk derivatives are suing the banks. As New York Times commentator Floyd Norris described last week, the legal situation doesn’t look good for the international banks. The home court always has an advantage, and every nation is sovereign, able to pass whatever laws it wants. (And as America’s case abundantly illustrates, judges need not be unbiased.)

The post-Soviet economies as well as Latin America must be watching attentively the path that Korea is clearing through international courts. The nightmare of international bankers is that these countries may bring the equivalent of a class action suit against the international diplomatic coercion mounted against these countries to lead them down the path of financial and economic suicide. "The Seoul Central District Court justified its decision [to admit the lawsuit] on the kind of logic that would apply in the United States to a lawsuit involving an unsophisticated individual investor and a fast-taking broker. The court pointed to questions of whether the contract was a suitable investment for the company, and to whether the risks were fully disclosed. The judgment also referred to the legal concept of "changed circumstances," concluding that the parties had expected the exchange rate to remain stable, that the change in circumstances was unforeseeable and that the losses would be too great for the company to bear."

As a second cause of action, Korea is claiming that the banks provided creditor for other financial institutions to bet against the very contracts the banks were selling Korea to "protect" its interests. So the banks knew that what they were selling was a time bomb, and therefore seem guilty of conflict of interest. Banks claim that they merely were selling goods with no warranty to "informed individuals." But the Korean parties in question were no more informed than were Iceland’s debtors. If a bank seeks to mislead and does not provide full disclosure, its victim cannot be said to be "informed." The proper English word is misinformed (viz. disinformation).

.

Speaking of disinformation, an important issue concerns the extent to which the big international banks may have conspired with domestic bankers and corporate managers to loot their companies. This is what corporate raiders have done for their junk-bond holders since the high tide of Drexel Burnham and Michael Milken in the 1980s. This would make the banks partners in crime. There needs to be an investigation of the lending pattern that these banks engaged in – including their aid in organizing offshore money laundering and tax evasion to their customers. No wonder the IMF and British bankers are demanding that Iceland make up its mind in a hurry, and commit itself to pay astronomical debts without taking the time to ask just how they are to pay – and investigating the creditor banks’ overall lending pattern!

Bearing the above in mind, I suppose I can tell Icelandic politicians that I have good news regarding the fate of their country’s foreign and domestic debt: No nation ever has paid its debts. As I noted above, this means that the real question is not whether or not they will be paid, but how not to pay these debts. How will the game play out – in the political sphere, in popular ideology, and in the courts at home and abroad?

The question is whether Iceland will let bankruptcy tear apart its economy slowly, transferring property from debtors to creditors, from Icelandic citizens to foreigners, and from the public domain and national taxing power to the international financial class. Or, will Iceland see where the inherent mathematics of debt are leading, and draw the line? At what point will it say "We won’t pay. These debts are immoral, uneconomic and anti-democratic." Do they want to continue the fight by Enlightenment and Progressive Era social democracy, or the alternative – a lapse back into neofeudal debt peonage?