Christmas tree in the home of Wilbur and Orville Wright at 7 Hawthorn Street in Dayton, Ohio, three years before their famous flight

Ilargi: I will leave the stage to our friend VK, who writes a stream of consciousness inspired article on what plagues our financial systems. For me, just this one point from the news today:

It’s time to take a closer look at the FDIC. Closing banks has become much more costly lately. The FDIC is now taking over banks outright and building bridge banks, all because no buyers can be found for the banks that are closed. Obviously, this greatly increases losses to the FDIC fund. Consequently, banks that do takeover failed peers must be getting some real sweetheart deals out there.

The FDIC plans to acquire substantial additional funding, has increased its 2010 operating budget by 55%(!) over this year, and is even attempting to securitize and sell bundles of troubled loans it gets stuck with. Obviously, then, more banks are expected to be closed in 2010 than the 140 shut so far in 2009. And the overall costs will be much higher too. How that rhymes with a recovering economy, I can't tell.

Here's VK:

VK: The persistent notion that there's only $1-2 trillion in losses remaining in the banking system, as some people conclude from what Roubini and others may have stated, is false; that would be peanuts. The Federal Reserve printed $1.55 trillion to buy up toxic MBS plus Treasury paper. But the problem has not been cured, in particular: most of the toxic debt still remains hidden through the application of shady accounting practices. There is no solution in sight in the current political paradigm.

Think about it this way: the US government has implicitly and explicitly guaranteed, loaned, subsidized and given away about $12.8 trillion to banks while these banks have only $10 trillion or so in real assets. Why is the government giving so much assistance, a sum far greater then all assets combined of the US banking system?

Simple really, the derivatives aka bets are far larger than global GDP, estimated to be between $500 trillion and $1,5 quadrillion. JP Morgan alone holds $90 trillion or so in derivatives while the entire US GDP per annum is no more than one-sixth of that, at $14-odd trillion.

So those bets have gone bad and gone wrong and they have been kept hidden in the broom cupboard thanks to creative fictional accounting practices, in level 3 assets on bank balance sheets, and in off balance sheet items.

The losses are real, the bets went bad, and Washington is attempting a show of CONfidence to prevent a systemic collapse. But when Mr. Market calls the government's bluff, and he will, then people will realize the US Government is the naked emperor, with no money to back up those guarantees for failed and long dead enterprises.

There are three things in life that man can't prevent - death, taxes and Mr. Market calling the bluff.

See, Mr. Market is a master illusionist, is he not? Evidence you say?!

First he creates a mini panic, a preview if you will, that has many people crying out, "head for the hills", "rapids ahead!", then he deftly creates a slope of hope, which we are on now for the moment, where all the suckers who ran for the hills and paddled away from the rapids and in the process lost a few trillion here and there, realize how 'naive' they were and start buying any risky asset in sight. Gotta recoup those losses they say!

This year Mr. Market has gotten quite a leg up in emerging markets, what with Brazil rising 80% and India up by 70%, the anti-USD play evolving into a dollar carry trade and giving rise to bubbleicious bubbles in Asia, gold, stocks, and with corporate bond yields declining all year long. Alas, Mr. Market never makes it too easy and has been giving people cause for worry. What is it with those pesky 10 Year bonds yielding 3.5%, can't they sniff the inflation ahead people ask, why are they priced so high? Also, why did the difference between the long end of the curve and short end of the curve reach new highs recently?

Mr. Market gives hints to those who see and those who listen. What goes up, must come down as the old cliché goes. Bill Bonner puts it best, "The extent of the correction is equal and opposite to the deception that preceded it." And my, what deception we had! A glorious age of mankind was dawning we were told, that of stable growth, the end of recessions, scientific economic theory and a gilded age of prosperity.

So Mr. Market gives us hints, hints not to listen to the fools, the ones that missed the crisis and are now predicting its early demise. The hints are obviously the rising USD over the last few days, the considerable fall in gold, the problems re-emanating across Dubai, Spain, Greece, Ireland etc. Looks like Mr. Market is saying that the flight to safety has begun and lord knows it will be grand. When those on the slope of hope get caught up at the greasy end, when they suddenly lose grip, with horror etched on their faces as they tumble away far down into the nether regions of the world.

So the USD will rise in value much to the shock of all. The economy is worsening and it's rising people will say? Maybe even double in value from present values, it seems likely given the amount of debt deflation occurring in the world. The dollar represents 65% of the world's money and as money gets scarcer, the USD will be the One eyed King of the blind and ill, oil will fall substantially, a return to 10 dollars per barrel or less is in the cards given how much demand is going to plummet next year, so forget about Sheikhs in Abu Dhabi bailing out their hapless cousins in Dubai. Gold must fall, eventually I see Gold returning to 600 or less, maybe kissing the DOW, the bottom will be in when the Dow/ Gold ratio reaches around 1.

Emerging markets will get battered hard, bitterly hard. They rose the fastest and they will fall the fastest. The wind will get sucked out of them much faster than the US because remember emerging markets are peripheries, the flight to safety will see them crumble as money rushes to the perceived safety of the core countries. Imagine a concentric circle crumbling from outside in.

The world will groan and moan, for as yet we have not seen a real bust, whether it's the gravity defying Australian kangaroo economy which must contract sharply as China's epic credit fuelled hangover will eventually end leading to a bursting resource bubble there and in the overvalued Australian dollar or the bubbly Canadian house price boom whose vintage is decidedly toxic or those overpriced box-like hovels in England people call homes, their true value must eventually come out as Mr. Market believes in the truth and nothing is quite like the light of truth to reveal the ugly toxic glory of all credit cretins.

We will also learn that all those factories in China are worth zero, as well as those in Korea and Japan, as the buyers of their goods are fast becoming broke, unemployed and homeless and those who still have a roof over their head will find out that those houses are worth close to Zero and my how wages will fall due to the cascading effects of the deflationary spiral! It will certainly be a sight to behold. Though you may not see much in your wallet or your bank account.

Corporate bonds will get hammered and many companies will default as they simply can't pay back or up. This will grievously damage or end many too big to bailout entities and heaven help them as countries decide that saving banks isn't a particularly good idea if they have to commit national suicide in the process. Even the strongest companies are not worth the risk, as cash flow will all but dry up, much like quality entertainment on US television at present, as hardly any exists.

Let's watch cash flow drying up in greater detail for a moment; the banks you see have borrowed trillions upon trillions of dollars from the rest of the world and each other. Between today and 2012-2013 the banks need to refinance around $7 trillion at the least (that's what they're telling us, it could be much higher).

Now a basic rule of capitalism and thus banking is that you obviously want to make a profit, greed and the self are the key building blocks of our capitalist system. So banks borrow cheaply and make loans at a higher rate, the spread is how they make a profit. Now currently banks are not making many loans, in fact both European and American banks are decreasing the amount of loans they make while holding onto record reserves of cash.

What they are doing is borrowing at 0% from the FED and using that to buy Treasuries that pay around 3.5% and currently since the market is rallying they are using that to go long via speculative positions.

It sounds like a good deal but when you think about the fact that they have borrowed at a much higher rate then 3.5% and that they still hold trillions upon trillions of derivatives that require interest payments on the liabilities side of the balance sheet, and that they hold trillions in deteriorating commercial real estate loans, mortgages, businesses loans, corporate bonds etc. on the asset side, you can sniff out the trouble they are in!

Now because the vast majority of money supply is credit and that supply of credit has been declining, the amount of cash in the economy is declining and will decline further due to the unwillingness of banks to lend and the fear that borrowers have of going into more debt then they already are in. Obviously at some point the borrower realizes that swimming is fun but only if your head is above the water!

So income streams from mortgages, commercial loans, small and medium sized companies start declining as these companies lack substantial cash flow to meet their loan obligations. When the assets remain marked to myth for a longer period of time, the cash flow declines start having very real impacts. As cash flowing into the banking system declines, how can banks meet their trillions in obligations in the form of loans, bonds, deposit interest and the like? In short, they can't.

So if less income is coming in from the asset side of your business, the less likely you are to be able to pay your liabilities regardless of how high you 'book' your level 3 assets. And if ever level 3 assets are allowed to be marked to market, you'll find that the whole bada bing is worth zilch instantly; what I would call a bada boom.

So Mr. Market will start calling the banks when serious cash flow problems start emerging, in today's slope of hope rally, participants such as the banks and corporations have issued a record amount of bonds to stave off their cash flow problems and keep operations going as they can't get loans. Trying to solve a debt problem by adding more debt is just plain silly akin to 'curing' a tumorous cancer by providing the patient with adrenalin jabs to keep him alive while he writhes in agony for longer. The next deflationary wave down then hits when market participants realize how bad the real economy is due to:

1) The hidden psychological (herding) forces. A crisis of confidence.

2) Declining cash flows, cash that is vital in keeping the economy afloat.

We will see a flight to safety and a cascade down in the markets along with declines in wages, prices and an increasing debt burden as real interest rates skyrocket, provoking downturns in world trade and the whole globalization whopeedoo train!

When the proverbial smelly stuff hits the fan, the long end of the curve is an attractive place to be, the differential between the long and short ends looks far too large. 30 year bonds will shoot up in price and go substantially down in yields. I'm thinking that Mr. Market is hinting at a huge flight to safety. This could see 30 year yields at 1% or less, it all depends on Mr. Market of course, he alone is the giant amongst men.

Lest we forget the midgets amongst men, we shall honour them as well, currently Mr. Market has led resource currencies and commodities to heights far above where they should be and soon we shall find out that they are going to get hammered and hammered hard into the ground. As the Chinese crack stimulus fades and the sheer force of the contraction we are facing will wipe out all pricing support as demand will evaporates into the ether.

Obviously as we see an increasing loss of confidence, a bank run could ensue and definitely accelerate events rapidly! We could see a cascade event/ tipping point in the middle of next year or earlier as people lose confidence in the system. Once fear grips the population, I suspect Mr. Market will be looking forward to creating bank holidays and closures of the stock market. Banning those 'evil' short sellers and jawboning the slope of hope recovery, expect great oratory from President Obama next year and an attempt to take on more debt by Congress in attempt to 'recover' and 'stabilize'.

Did I mention Mr. Market loves practical jokes?

Now there's the old adage, All men are created equal but some more so then others. 'Tis the same with debt really. Not all debt is equal, some of it is more useful then other debt, for example private sector debt is more capital efficient then public sector debt though both are socially inefficient in the long run but that is a story for another day. A corporation is going to use debt more efficiently then a government is ever going to, as it has a profit motive to extract the most out of that borrowed dollar.

Now things get interesting, the time of creation of that debt is also very relevant. As credit forms 99% of the money supply and because money supply must always grow given the present monetary paradigm, it is obvious that credit/debt created 20 years ago carried more bang for the buck and that credit/debt created 60 years ago carried even more than that!

In the 1970's a car, good affordable housing, a nice university education etc cost far less then it does today and on much lower incomes as well.

So in the 70's and 80's a dollar borrowed was worth much more then it is today. You could buy more land, more house, more car, more education and more stock! Today a dollar won't do much as it has steadily devalued over time by a process we all know and love called inflation whereby your purchasing power as well as borrowing power declines over time.

Moreover, our economies have hit the big fearsome brick wall of diminishing returns. Today we have a situation where for every dollar that an individual or a company borrows, the system gets out maybe 10 cents or less of growth. In the 1950's, it is estimated that every dollar borrowed would generate 3 dollars of growth. That's a large part of the reason why all those trillions in bailouts, guarantees, subsidies, loans etc are having such negligible impact.

So we have trillions of borrowing and record spending to get a few paltry billions in 'growth'.

A debt saturated society is thus faced with two conundrums as time progresses.

1) The ability to service the debt plus interest declines steadily over time leading to cash flow problems.

2) The usefulness of that extra dollar of debt also steadily declines. Thus we are moving towards a point where for every dollar borrowed we have a contraction (I was going to use that ghastly word 'negative growth' but decided against it) due to debt saturation.

Hence, the marginal cost of taking on one more dollar of debt will become detrimental to society as a whole, as the marginal benefit of that one more dollar is negative. This is precisely how societies decline and as in our present debt based monetary system, the principal must be paid with interest by society as a whole in one form or the other.

This is either done through:

1) A deflationary depression where debt is defaulted upon and living standards plummet and millions are left broke and homeless - a societal disaster.

2) A hyperinflation that leads to the complete debasement of the currency and the utter failure of the monetary system - a societal disaster.

Some deflationistas focus on the mechanics that will make deflation the driving force initially and for the foreseeable future - constrained lending by banks, hoarding of cash, the inability of the Fed to keep pace with credit destruction and the unwillingness of foreigners to finance government deficits indefinitely as their balance sheets are constrained by declining export income (we're looking at China and Japan, the Gulf). When, but only when, an economy has become isolated enough can hyperinflation take place, and as a reaction to deflation. The American economy knows no such isolation, and can therefore not be hyperinflated at the moment. In five years, yes, but the world will be a whole different place by then.

By the way, actually paying back the debt is impossible in a system that requires constant debt creation just to keep even, remember the Red Queen in Alice of Wonderland? One has to run faster just to keep up.

So next year we look all set to see the beginning of shortages of goods and services in the western world, as companies go bust due to their target market having barely enough money to survive. Bank runs and heightened fear are highly possible, but always remember at the height of that fear, Mr. Market will once again create a slope of hope much like 2009, but much worse, because at the time it will look like a God-send, a "recovery is finally here" will be the cry across the land. Here the battered and the wounded will be given hope and motivation, only to be suckered into finding out they are yet again on a slope of hope.

The slope of hope that leads to the abyss. I hope one now appreciates and understands Ilargi's all time classic line, "Heads you lose, tails you die".

Ilargi: Did you donate to the Automatic Earth Christmas Fund yet? Wouldn't that just make you sleep so much more peacefully?

Depression on Wheels

by Bill Bonner

When the price of oil hit $150 a barrel, the first major alarm sounded. Something was wrong. Now we have a clearer idea of what it was. To make a long story short, leading economists have a one-stop solution for just about everything: stimulate consumer spending. But $150 oil warned us: continue down that road and you will run out of gas. There isn’t enough oil in the world to allow US-style consumption for everyone.

Two weeks ago, Dubai gave us another wake-up call. Thought to be risk-free, since it was implicitly backed by all the oil in the Middle East, Dubai World nevertheless stopped paying its debts. And this week yet another bell banged our eyes open. Greece announced first that it would not try to reduce its deficits…then, that it would. Hearing the news, the financial world rolled over and went back to sleep. But The Wall Street Journal offered a hint of trouble to come: "Markets force Greek promise to slash deficit," said its page one headline.

If markets could force the Greeks to trim their deficit – about 13% of GDP…not far from the US level – could they not force Britain and America too? Coming right to the point, the fixers face not just one crisis, but many. They have a growth model that no longer works. They have aging populations and social welfare obligations that can’t be met. They have limits on available resources, including the most basic ones – land, water, and energy. They have a money system headed for a crack-up, and an economic theory that was only effective when it wasn’t necessary. Now that it is needed, the Keynesian fix is useless. If a recovery depends on borrowed money, what do you do when lenders won’t give you any?

But let us backtrack to a smaller insight. Then we will stretch for a bigger one. Americans are supposed to be insatiable shoppers. For at least three decades, the world counted on it. It was the growth model for almost all the Asian manufacturing economies…and for resource producers everywhere. But as we approach the biggest shopping season of the year, a survey of consumers signals an earthquake. Americans plan to spend an average of 15% less during this holiday season than the year before. Only 35% say they will take advantage of post-Christmas sales, traditionally when the stores unload unwanted inventory. They seem to be satiable after all.

Push come to shove, Americans react like everyone else. Now, they are being shoved into a new world, very different from the one they have come to know. In 1973, the American working stiff went into a decline. His weekly earnings, in real terms, went down for the next 36 years. The typical worker earned the equivalent of $325 a week in 1973…adjusted to constant 1982 dollars. By US official accounting he was down to $275 a week in 2009. Unofficial estimates put the loss as high as two-thirds of his purchasing power.

Yet, his spending increased anyway. How? He squeezed the rest of the world. The US trade gap began to go seriously negative in 1992. By 2006-2007, foreigners were shipping to America nearly $900 billion more per year in goods and services than they received in exchange. This gave the typical American a standard of living few people could afford; too bad, he wasn’t one of them. Now he’s up against billions of Patels and Hus. They work for less. They save more. They want more stuff too. And they’re suspicious of the dollar.

Their economies are growing faster…and better. Because they don’t have 50 years of accumulated success on their backs. That’s the trouble with success; it adds weight. In their heyday, the mature economies could afford to squander and regulate. But that trend, too, is reaching its limits. Even without the cost of ‘stimulus,’ practically all the world’s leading economies are headed for insolvency. And yet, this week, Paul Krugman gave his solution to the weak results from stimulus spending so far – add $2 trillion more!

All of a sudden, the most reliable givens of the past half a century aren’t given any more. Americans were the big winners of the post-WWII period. They got used to it. At first, they wanted to make things; later they just wanted to have them. And with the benefit of cheap oil and resources, and then cheap labor and cheap credit, they were able to get more stuff than any race ever had. Now they are shackled to it, unable to move forward or to back up. Meanwhile, Europe – led by post-war neoclassical Jacques Rueff in France and Ludwig Erhard in Germany – pursued a different course. While Americans subsidized consumption, Europe taxed it. Credit was expensive, not cheap.

And then, the European Central Bank had the great advantage of having a chief banker whom no one paid any attention to. He might talk about stimulating consumption, but he did nothing. And now the world is reckoning with much more than a consumer debt bubble. It is reckoning with a depression on wheels…the end of the consumer spending era. We don’t know what kind of world will take its place. But it won’t be the one the feds are trying so desperately to save.

The Dark Gray Swan: No More Foreign Dollars With Which To Buy US Treasuries

by Tyler Durden

Could the next black/green/dark gray swan be so obvious that it has avoided everyone? Well, except for the deputy governor of the Bank of China, who just gave the world a startling reminder of economics 101, when he said that it is "getting harder for governments to buy United States Treasuries because the US's shrinking current-account gap is reducing the supply of dollars overseas." Oops.The funny thing about natural (and economic) systems: they can only be pushed so far before they snap back to default state. With the entire world embarking on an unprecedented spree of domestic bubble blowing to mask the collapse in global GDP, everyone forgot to trade. Zero Hedge has long emphasized that the drop in world trade can only sustain for so long before it brings the current destabilized system back to some form of equilibrium.

Because with every country intent on merely printing more of its own currency, whether it is to build bridges or to make the stock of electronic book fads trade at 100x earnings, said countries ran out of non-domestic cash. Alas, this is most critical for the United States, now that Treasury monetization is over, as the US needs to constantly find foreign buyers of its debt to fund unsustainable deficits. Foreign buyers who have US dollars. And according to Shanghai Daily, this could be a big, big problem.Here is what the BOC's Zhu Min said earlier:

The United States cannot force foreign governments to increase their holdings of Treasuries," Zhu said, according to an audio recording of his remarks. "Double the holdings? It is definitely impossible."

"The US current account deficit is falling as residents' savings increase, so its trade turnover is falling, which means the US is supplying fewer dollars to the rest of the world," he added. "The world does not have so much money to buy more US Treasuries."In a nutshell, in printing trillions of assorted securities, the Treasury has soaked up the world's dollars, which due to US banks not lending, is sitting and collecting dust in the form of bank excess reserves. These excess reserves can not be used to buy Treasuries and MBS as that would be literal monetization (as opposed to the figurative one which is what QE has been). And the world is running out of dollars with which to buy Treasuries.

Does this mean that the "world" will be forced to buy dollars, and thus spike the value of the greenback? Not necessarily:

In a discussion on the global role of the dollar, Zhu told an academic audience that it was inevitable that the dollar would continue to fall in value because Washington continued to issue more Treasuries to finance its deficit spending.Critics of this line of thought can point out that China still has trillions in foreign exchange reserves. However, even as China has been selling mortgage backed securities almost as fast as PIMCO, it has not been buying treasuries: China's Treasury holdings have been flat at exactly $800 billion since May 2009. In the lesser of two maturity evils (the instantaneous, dollar bill, and the long-dated, the 30 Year) China has followed in the footsteps of so many millions of High Frequency Traders opting for that which can be liquidated instantaneously.

A different read of Zhu's statement is that the US should no longer rely on China for funding its bottomless deficits. And if that is the case, things are about to get much worse as the Fed has no choice but to turn the monetization machine on turbo.

States Scramble to Close New Budget Gaps

The patches used by states on their ailing budgets just months ago are now failing. Ohio lawmakers were expected late Thursday to vote on a compromise reached with Gov. Ted Strickland to avoid cutting education budgets an average of 10% on Jan. 1. In Arizona, lawmakers met in a special session Thursday -- their fourth on the budget this year -- to grapple with a new deficit. And in New York, Democratic Gov. David Paterson said Sunday he would postpone paying $750 million of state bills to avert a cash crunch.

Many states eliminated expected deficits earlier this year with budget cuts, tax increases, short-term borrowing, accounting moves and planned gambling expansions. But despite a slight improvement in the U.S. economy, states are now finding those measures didn't go far enough. Tax collections continue to trail projections in some states, and court rulings and political battles have blocked some gap-filling moves. Plus, some legislatures didn't fully deal with the deficits, leaving the toughest decisions to governors. All states, except Vermont, have at least a limited requirement of a balanced budget.Only a few states now have cash-flow problems. But if revenues continue to fall below expectations, the list could grow, said Scott Pattison, executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers. "That's certainly a concern for bond-rating agencies," he said. "It shows how bad things are." A Dec. 2 report from the budget officers' group and the National Governors Association said states have cut $55.7 billion from budgets in the current fiscal year, which for most began July 1. Even with the cuts, deficits total $14.8 billion. States' general-fund spending is expected to decline 5.4%, the sharpest drop since data collection began in 1979, the groups said.

States also have enacted tax and fee increases expected to raise $23.9 billion, the largest hike the group has recorded. In Ohio, a plan approved earlier this year to install video lottery machines at horse-racing tracks was expected to raise $851 million for schools. But the Ohio Supreme Court blocked the plan in September, saying it must be put to a statewide vote. Mr. Strickland, a Democrat, wanted lawmakers to suspend a 4.2% income-tax cut that took effect this year, to compensate for the lost revenue. Otherwise, he said, K-12 and higher-education budgets would have to be cut by $851 million. The cuts would jeopardize matching funds from the federal stimulus package.

Republicans, who control the Ohio Senate, said they couldn't get enough votes for the plan unless it was paired with changes to construction-spending laws that Democrats said shouldn't be rushed. "If the Senate majority is going to vote for a tax freeze or tax increase, we want to make sure our tax dollars are being spent as efficiently as possible," Senate Finance Chairman John Carey said. On Thursday, Mr. Strickland reached a compromise with lawmakers that involved suspending the tax cut and also includes establishing three pilot projects at universities that would use new construction procedures.

States filled 30% to 40% of their budget gaps with federal stimulus money. They were allotted about $250 billion of the $787 billion stimulus package, most of which will have been disbursed by the end of next year. The U.S. House on Wednesday passed a separate $154 billion package that includes $23 billion for states to pay teachers' salaries and $23.5 billion to pick up some state Medicaid costs.

In Arizona, Republican Gov. Jan Brewer convened a special legislative session Thursday to consider about $200 million in spending cuts and fund transfers. Although the state made $452 million in budget cuts and other changes in November, slumping tax collections mean the legislature faces a $1.6 billion shortfall. Arizona took out a $700 million credit line from Bank of America Corp. in November to pay bills, but that credit line was spent within days.

State Treasurer Dean Martin said if the state wasn't able to raise an expected $737 million next month by selling several buildings, Arizona might have to issue IOUs. The 2010 elections, when 37 governors will be chosen, are complicating the budget fights. In Illinois, Gov. Pat Quinn recently wanted to borrow an additional $500 million to address a portion of the state's $4.4 billion in unpaid bills, on top of $2.25 billion in short-term borrowings. But his rival in the Democratic primary, state comptroller Daniel Hynes, blocked the plan.

The Second Wave is Already Ashore

The second wave of ARM resets and foreclosures might come sooner than you think. According to Whitney Tilson and Glenn Tongue of T2 Partners, the experts on this subject, about 80% of option ARMs are negatively amortizing. Meaning these so-called top-tier borrowers are heading further into the hole. Once their rates reset, they could be in serious trouble.And that could be happening very soon:

The chart above, which should look familiar, shows the two peaks in this long-term housing conundrum. The first mountain is comprised of subprime ARM resets. And the second is mostly constructed of option ARM resets. We appear to be in the eye of the storm.

That alone shook our nerves when we first discovered it. But it was a different chart in Tilson and Tongue’s most recent presentation that really got us startled… It’s also the reason I’m predicting the dollar spike in 2010.

Instead of resetting as expected after the first five years, many option ARMs are so negatively amortized that they are hitting their automatic reset cap.

That means they are resetting early…like right now — with unemployment reaching quarter-century highs every month, and a massive number of homeowners about to receive mortgage bills for two-three times what they are used to paying.

It takes anywhere between three-12 months for most homes to actually go into foreclosure. It’s tough to say exactly when the storm will come. But my guess is the second half of 2010.

US pensions go bust, gold crashes, China flops, Bunds soar, predicts Saxo

America's Social Security Trust Fund will go bankrupt; both gold and the Japanese yen will crash; and China's currency will devalue as bad loans catch up with the over-stretched banking system – all in the course of 2010. The annual "Outrageous Predictions" of Denmark's Saxo Bank are not for the faint-hearted, though there is good news for some.

David Karsboel, chief economist, thinks the US trade balance may go into surplus for the first time since the mid-1970s, benefiting from the delayed effects of the weak dollar. Yields on sovereign bonds – the goods ones, not the bonds of quasi-basket cases such as Club Med, the UK, or Japan – will plummet as deflation raises its ugly head again later in 2010. The 10-year German Bund yield will fall to 2.25pc. "Bunds are the ultimate safe-haven if something goes wrong, perhaps in Greece. We may even see some safe-haven buying of US Treasuries as well, despite the irresponsible fiscal policies in the US," he said.

The US Social Security fund will finally tip over, technically going bust. "Ever since the good years of the 1960s politicians have been taking the money and spending it instead of setting it aside for the fund, but next year it will go into deficit for the first time as US demography turns. "The fund is going to need a bail-out, financed by higher taxes, more borrowing, or more printing." Gold will spiral down to $870 an ounce from its all-time high above $1,200 last month.

"There is a lot of speculative hot money in the gold price right now that needs to be shaken out. In the long run we're bullish on gold, and think it could reach $1,500 over the next five years," he said. "In fact, we would like to see the restoration of a gold standard to prevent the sort of excesses we have seen. The world has been in a bubble since the mid-1990s. They are still blowing new bubbles to keep it all going, but each bubble is shorter and shorter. It is frightening, and is all going to end in tears," he said.

Saxo Bank is squarely in the camp of Sino-sceptics, noting that China's alleged industrial and GDP growth does not tally with weak electricity use. In any case, growth has been built on an investment bubble creating "massive spare capacity". It says 2010 will be the year when it becomes clear that there is not enough demand in the world to absorb all their excess production. The yuan will devalue by 5pc, defying near universal expectations of a sharp appreciation. As for Japan, Saxo advises clients to sell the overvalued currency as the yen carry trade comes back into vogue and the dollar rebound gains traction. The yen will weaken from 89 yen to 110 yen against the dollar.

Saxo advises clients to dump 10-year Japanese bonds, doubting that current rates of 1.26pc are remotely sustainable at time when the public debt is exploding towards 227pc of GDP. "The yield is ridiculously low. The Japanese are no longer saving much, and they have hardly any economic growth," he said. However, Tokyo's TSE index of small stocks is a buy with a price to book ratio of 0.77, just about the cheapest stocks in the world. And lastly, if you jumped on the lucrative sugar bandwagon in 2009 as India's drought played havoc with supply, get off soon. Bad weather rarely persists. Sugar is about to crash by a third. Saxo Bank offers its thoughts as "Black Swan" risks that could paddle up quietly and bite you, rather than absolute predictions. Take them in the right spirit.

If it walks like deflation and talks like deflation....

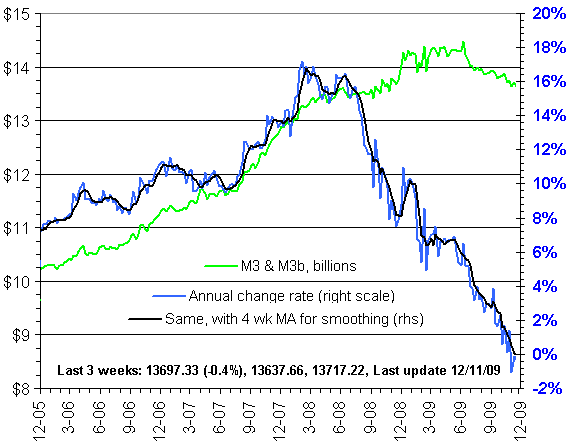

For all the talk about inflation appearing sometime in our not-too-distant future and, according to Milton Friedman, rising prices still being a monetary phenomenon, you sure don’t hear too many people talking about the broadest measure of the money supply – M3.

Reconstructed over at nowandfutures for about the last three years after the Federal Reserve discontinued it, much to the chagrin (or, maybe, delight) of those conspiracy minded individuals who viewed the move as a cover-up on the grandest of scales, it’s hard to see how consumer prices are going to be bid higher anytime soon, given a chart like the one above.

Of course, if banks ever start lending some of their massive reserves, an entirely different dynamic could quickly develop and the recent trend could quickly reverse, but, fortunately, our central bank leaders have assured us that they’re on top of that particular situation.

Seven U.S. banks closed by regulators; failures at 140

Seven U.S. banks were closed by regulators on Friday, bring the total this year to 140 as the effects of the credit crisis continued to be felt across the country. What's more, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. established temporary institutions to help close two of the failed banks. Atlanta-based RockBridge Commercial Bank became the 25th Georgia-based bank to fail this year. The FDIC was unable to find another institution to take over the failed bank, and so will mail checks to retail depositors for insured funds.

RockBridge Commercial Bank had roughly $294 million in assets and $291.7 million in deposits as of Sept. 30. Its failure will cost the federal deposit-insurance fund $124.2 million, the regulator said. Panama City, Fla.-based Peoples First Community Bank became the 14th to fail in that state in 2009. Peoples First Community Bank had $1.7 billion in deposits as of Sept. 30, and Gulfport, Miss.-based Hancock Bank has agreed to assume those deposits.

Peoples First Community Bank's failure will cost the deposit-insurance fund $556.7 million, according to the FDIC. New Baltimore, Mich.-based Citizens State Bank's failure will cost the deposit-insurance fund $76.6 million, with the FDIC creating the Deposit Insurance National Bank of New Baltimore to protect depositors of Citizens State Bank. The new bank will remain open for 45 days to allow depositors to access insured deposits and open an account elsewhere, the agency said. Columbus, Ohio-based Huntington National Bank will operate the DINB under contract with the FDIC.

An FDIC spokesman said the agency has created such bridge banks "several times this year and in previous years." Irondale, Ala.-based New South Federal Savings Bank also was closed by regulators Friday. The bank had $1.2 billion in deposits as of Sept. 30, which will be assumed by Plano, Texas-based Beal Bank, the FDIC added. New South Federal Savings Bank's failure will cost the deposit-insurance fund $212.3 million. Springfield, Ill.-based Independent Bankers' Bank was closed, with $511.5 million in deposits as of Sept. 30.

The FDIC said it created the Independent Bankers' Bank Bridge Bank to allow client banks of Independent Bankers' Bank "to maintain their correspondent banking relationship with the least amount of disruption." Independent Bankers' Bank's failure will cost the deposit-insurance fund $68.4 million. Two Southern California banks were closed Friday, the 16th and 17th such failures in the Golden State as a whole. First Federal Bank of California in Santa Monica was taken over by regulators. OneWest Bank of Pasadena will assume all of its deposits and take over First Federal's 39 branches, the FDIC said.

OneWest Bank agreed to purchase all of the $6.1 billion in First Federal Bank assets and did not pay the FDIC a premium for the $4.5 billion in total deposits; the hit to the deposit-insurance fund will be $146 million. Separately, La Jolla, Calif.-based Imperial Capital Bank was closed. It had $2.8 billion in deposits as of Sept. 30, the FDIC said, and its failure will cost the deposit-insurance fund $619.2 million. City National Bank of Los Angeles is assuming all of the deposits in the "least costly" resolution, according to the agency.

FDIC to securitize, sell up to $30 billion in troubled loans in Q1 2010

Latest in bad debt dumping from National Mortgage News:The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. is contemplating securitizing at least $10 billion of delinquent and underperforming whole loans belonging to failed banks in the first quarter, according to investment banking sources who have been briefed about the plan. These sources, requesting their names not be used, said the bond issuance could rise to as much as $30 billion. The FDIC will be the issuer of record on the MBS.

"Right now it’s a prototype they’re talking about," said a source. At press time, the agency had not returned telephone calls about the matter. The FDIC has hired former secondary market executives that worked for UBS Securities and Option One Mortgage to advise them on the securitization process, said one advisor. "These are smart guys who know their way around the securitization business," he said.

The FDIC may have to guarantee payment on the bonds to lure investors.

Agencies in a Brawl for Control Over Banks

In the darkest days of the financial crisis a year ago, Sheila Bair was hailed for having predicted the housing bust. Today, the chief of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. is fighting for her agency's future. The FDIC was set up in 1933 as part of a successful attempt to rescue the banking system, and its deposit guarantees helped save the industry in the present crisis. But as lawmakers hash out the biggest overhaul of financial regulations since the Great Depression, the FDIC could wind up a shadow of its former self.

Connecticut Democrat Christopher Dodd, the Senate Banking Committee chairman, has proposed revoking almost all of Ms. Bair's powers to supervise banks, as part of a sweeping financial-regulation bill now under consideration in the Senate. That would leave Ms. Bair in charge of an agency whose primary role is to clean up banks after they fail, with little part in monitoring them before problems erupt. So, Ms. Bair has been working for months to beat back the idea. She has met with nearly all of the 23 lawmakers on Sen. Dodd's panel, including at least once with the chairman. In the fight to reshape regulation, Ms. Bair has clashed bitterly with Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, irked some of her own employees and angered bankers who say the FDIC chairman is stifling their businesses.

There are early signs her forceful lobbying may be working. The House version of the financial regulatory overhaul, which passed last week, is much more FDIC-friendly, thanks in part to her frequent presence on the Hill, say some representatives. Aides say Sen. Dodd is now considering a new proposal that would allow the FDIC to retain its oversight of smaller, community-owned banks, while creating a new agency to oversee national banks. Ms. Bair's struggle is part of a broader battle over the future shape of the apparatus that regulates the U.S. financial system.

In the wake of the crisis, virtually every agency involved stands accused of being asleep at the switch, and officials who led the response are under fire. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, who by the end of next month faces a Senate vote on his re-appointment to a second four-year term, is trying to fight off an assault on the central bank's powers. Mr. Geithner is frequently blasted by the left for being too close to Wall Street. "The FDIC is scrappy, we always have to fight to be heard," Ms. Bair, 55 years old, said in an interview.

Before being tapped to head the FDIC, Ms. Bair bounced between Washington, academia and the private sector in a series of mostly low-profile jobs. She studied philosophy as an undergraduate at the University of Kansas, working for a time as a bank teller, then graduated from the law school. Later, she headed to Capitol Hill as a lawyer for Sen. Bob Dole, a Republican from her state. Enamored of politics, she ran for a Kansas seat in the U.S. Congress in 1990 but lost in the Republican primary by fewer than 1,000 votes to local banker Dick Nichols. (People close to Ms. Bair say she has no plans for another run, and intends to work in academia or run a nonprofit when her FDIC term ends in 2011.)

She went back to Washington for a post on the board of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the agency that regulates derivatives trading, then worked in government relations for the New York Stock Exchange before being tapped in 2001 as an assistant Treasury secretary. She left after a year to teach finance at the University of Massachusetts, saying she wanted to spend more time with her family. There she wrote a children's book about financial education, "Rock, Brock, and the Savings Shock," a cautionary tale about twin brothers and the perils of overspending.

In 2006, Ms. Bair was named chairman of the FDIC, which regulates more than 5,000 lenders across the U.S. and runs the fund that insures deposits in the case of bank failures. For most Americans, the FDIC long was just a sticker in banks' windows. Financial markets were relatively calm. No bank had failed since 2004. The FDIC was dwarfed in stature by the Federal Reserve, whose banking regulatory powers overlap those of the agency.

Ms. Bair first looked into the risks of subprime lending while at the Treasury. On joining the FDIC, she directed the agency to purchase loan data from a private company to get a better sense of what a housing bust might look like. Ms. Bair says she found the figures alarming. Close to 75% of securitized subprime loans from 2004 and 2005 were the kind of loans on which payments ballooned after two or three years, creating a potential time bomb.

With this in mind, early in 2007 Ms. Bair started warning of a wave of foreclosures well ahead of other regulators, most politicians and the White House that appointed her. The industry's problems -- failures, rising losses on loans, evaporating capital cushions -- soon started to mount. Ms. Bair added staff, and has about 7,000 employees today from 4,500 when she took over. The FDIC said Tuesday it planned to add an additional 1,600 staffers in 2010 and nearly double the money in its budget to deal with an expected rise in bank failures.

As some of her predictions proved true, Ms. Bair became one of the most recognizable personas of the crisis. On Sept. 17, 2008, two days after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, Ms. Bair sat alone on a House Financial Services Committee panel, warning lawmakers that more needed to be done to help homeowners avoid foreclosure. Giving the seat to a solo witness is a distinction usually reserved for cabinet secretaries and Federal Reserve chairmen.

Inside the government, however, strains were starting to show. Several people close to the FDIC say some staffers were frustrated by Ms. Bair's management style, which one described as "head-cracking" at times. They say some at the agency call her "She Bear," evoking a mother bear: fiercely protective and aggressive when provoked. A spokesman for Ms. Bair says she's not familiar with the term. Early in her tenure, Ms. Bair blasted a group of employees for handing her two staff-written economic reports with conflicting data, according to a person familiar with the matter. Several staffers say they were so worried about making the same mistake again they spent days checking and cross-checking future reports to avoid a reprimand.

In her three years at the FDIC, Ms. Bair had three different people in charge of congressional relations and three different general counsels, moves some employees say were a sign that Ms. Bair was difficult to work for. The FDIC says these departures don't reflect employee dissatisfaction, and say internal surveys show morale has steadily climbed since Ms. Bair took office.

Once the financial crisis struck, Ms. Bair and then-Federal Reserve Bank of New York President Timothy Geithner sometimes tangled. Mr. Geithner often pressed for dramatic interventions to stabilize the economy. Ms. Bair often resisted, as some of the steps might have made the FDIC liable for trillions of dollars of losses if the economy cratered, say people familiar with the matter.

One of Mr. Geithner's first tasks upon becoming Treasury secretary in January was overhauling financial regulation. FDIC officials were frequently left out of the negotiations. They weren't always consulted on key details, say government officials, such as what role the agency would play in monitoring risks in the financial system. A person close to the planning process said the FDIC was left out because the new Obama administration was keeping many decisions internal, and because it feared Ms. Bair, a Republican, might be at odds with some of the points. White House officials deferred to the Treasury for comment, and the Treasury declined to respond.

The White House's June announcement of its overhaul plan stunned FDIC officials, according to several people familiar with the matter. Mr. Geithner proposed taking away the agency's power to enforce consumer-protection laws, giving the Federal Reserve more power over financial institutions and putting the Fed chairman on Ms. Bair's five-member board of directors. The plan did envision the FDIC having more power in one area: taking over and breaking up failing financial companies, rather than just banks.

Ms. Bair viewed the plan as mostly marginalizing her agency and letting the Fed move into FDIC territory, according to people familiar with the matter. On the last Friday in July, Mr. Geithner invited Ms. Bair and several other regulators to a gathering in a Treasury conference room. Several people who attended the meeting described it as the most confrontational meeting of financial regulators in years. Mr. Geithner immediately lit into the regulators in an expletive-laced fury, at times raising his voice to the verge of shouting, according to several people familiar with the meeting. "Everyone needs to get on the same page," he said, according to one of those people. This is too "f-" important, he said.

Ms. Bair sat several seats away. There were close to two dozen officials and aides in the room, including Mr. Bernanke, but some present believed Mr. Geithner's comments were directed at her. Others at the meeting, including Mr. Bernanke, tried to smooth over the tension. A Fed spokeswoman declined to comment on the meeting. Ms. Bair quietly fumed. When she spoke, her voice was pointed and direct. She accused Mr. Geithner of not briefing regulators on details of the financial plan before it was unveiled, people familiar with the meeting said.

Ms. Bair's political struggles have been paralleled by mounting financial struggles at the FDIC. A cascade of bank failures wiped out the FDIC's deposit-insurance fund in the third quarter of this year, pushing it into negative territory for the first time since the savings-and-loan crisis of the early 1990s. After 133 failures so far this year, the balance at the end of September stands at negative $8.2 billion. One of Ms. Bair's biggest tests this year came when Sen. Dodd moved forward with his plan -- the Senate's version of the financial overhaul, which would strip the FDIC of much of its power. He envisioned a single national banking regulator, taking the place of the current four, and leaving the FDIC with one job: cleaning up failed banks.

Ms. Bair has told lawmakers that the FDIC's supervision of banks hasn't been perfect. Several FDIC Inspector General reports have found that the agency allowed some community banks to load up on speculative real-estate loans that eventually caused them to fail. Ms. Bair has argued that taking away her agency's ability to oversee banks and putting all regulatory abilities under one agency would put too much power in one centralized place. "If they do the right thing, then maybe we're OK, but if they do the wrong thing, we're really in the soup," she told a congressional hearing in October.

Sen. Dodd's proposal immediately ran into resistance, including from some lawmakers Ms. Bair met with to plead her case. A spokeswoman for Sen. Dodd says he has not backed off from a single-regulator plan, but is working with lawmakers to build a consensus. Lawmakers, meanwhile, are bristling with stories from people back in their districts about how FDIC examiners have been second-guessing loan decisions made by local bankers, leading many politicians to accuse regulators of stifling the economic recovery.

"An agency takes its culture, its direction from the top," says Sanford Brown, a former bank regulator at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and now a managing partner in the Dallas law office of Bracewell & Giuliani LLP. Mr. Brown says several of his bank clients have called him to complain that the FDIC is forcing them to write down the value of loans that the banks say have more value. Ms. Bair brushes aside criticism of the agency's handling of banks. Lenders are trying "to personalize this to me somehow," she says. "Just because some CEO wants to call me and get a different outcome, that doesn't happen. If that makes them unhappy, too bad."

FDIC Increases Budget on Expectations of Mounting Bank Failures

Although signs of economic recovery have begun to take shape, don’t expect the number of bank collapses to ease – that’s the opinion of the federal agency that insures the nation’s financial institutions. The FDIC is boosting its 2010 budget by a hefty 55 percent and adding staff in order to cope with another round of excessive bank failures next year. Earlier this week, the agency’s board approved a $4.0 billion corporate operating budget for the upcoming fiscal year, up from the current 2009 budget of $2.6 billion.

"The 2010 budget is a prudent and measured response to current conditions in the banking industry," said FDIC Chairman Sheila Bair. "It will ensure that we are prepared to handle an even-larger number of bank failures next year, if that becomes necessary, and to provide regulatory oversight for an even larger number of troubled institutions." The agency said in a written statement that the budget increase is primarily due to the cyclical nature of bank failures. The receivership funding component of the 2010 budget, will be $2.5 billion, up from $1.3 billion in 2009. This includes funding for the continuing work associated with bank failures that have occurred since the onset of the financial crisis two years ago.

Funding for the budget increase will come solely from deposit insurance premiums paid by individual banks around the country. The FDIC has implemented a new payment structure requiring insured institutions to prepay three years worth of fees. Collection of this extra capital begins December 30, and is expected to yield over $45 billion to help cover the cost of bank collapses. In conjunction with its approval of the 2010 operating budget, the FDIC’s board also authorized a staff increase. In 2010, the agency will employ 8,653, up from 7,010 in 2009. Almost all the additional staff will be hired on a temporary basis, to assist with bank closings, the management and sale of failed banks’ assets, and supervisory examinations of the nation’s financial institutions.

As DSNews.com previously reported, the FDIC has already opened a large satellite office in Jacksonville, Florida with a crew of nearly 500 specialists to help handle closings in that part of the country. Banks have been going under at a particularly rapid pace in Florida, as well as neighboring Georgia. There have been 133 bank seizures so far this year, compared to 25 in 2008, only three in 2007, and none in 2006 and 2005. The FDIC keeps a watchlist of what it considers to be "problem" banks, and the number of names on that list has climbed to 552 – another sign that a steady stream of institutional failures will likely characterize 2010. Bair says she expects the cost of bank failures between 2009 and 2013 to reach about $100 billion.

Moody's 'axe blow' to rating on Spanish debts

The debt crisis sweeping southern Europe has deepened after US credit-rating agency Moody's downgraded €112bn (£100m) of Spanish mortgage debt and slashed the ratings of Catalunia and a raft of regions with ballooning state deficits. Spain's media called the move an "axe blow", fearing a domino effect through the country's debt markets. Credit default swaps measuring the risk on Spanish sovereign bonds jumped 10 basis point to 101 yesterday. Moody's downgraded a third of the entire stock of Spanish mortgage bonds or "cedulas" – covered bonds deemed safer than US sub-prime securities – but also made from debt that is sliced into packages. Most were cut from AAA (Aaa) to Aa1. They are largely owned by German or French banks and pension funds.

The agency said the Spanish savings banks that issued the bonds are heavily exposed to Spain's property crash. Moody's said it had based its stress test on assumptions of a 45pc fall in house prices. The scale of yesterday's action is huge, roughly equal to a trillion-dollar downgrade in US terms. Spanish banks avoided damage from the global credit crunch because they eschewed US toxic debt, but their own internal sub-prime crisis is slowly catching up with them. Professor Luis Garciano from the London School of Economics said Spain's property bubble left an over-supply of 1.5m homes, the most concentrated glut in the world. The country topped Moody's worldwide "misery index" this week as a result of its fiscal deficit and high jobless rate – now 19pc, and 41pc for youth. The IMF expects the country to grind on in near perma-slump next year.

Spain's travails came as bonds and equities took another pounding in Greece, where Communist unions launched a 24-hour strike and workers marched in protest against austerity measures. The sole good news for battered countries on the eurozone fringes was that Ireland managed to eke out growth in the third quarter, beating the UK out of recession. The feat is unlikely to last as draconian wage cuts come into force in January. The economy has shrunk 7.4pc over the last year. It is expected to relapse next year in what amounts to a three-year depression.

Richard Bruton, Fine Gael's finance spokesman, said it would be "dangerously complacent" to assume that Ireland had turned the corner. Profits from multinationals based in Ireland inflated the GDP figures. The domestic economy (GNP) contracted by 1.4pc. Ireland has been widely praised for taking the drastic steps needed to restore credibility after swinging from boom to bust. Its flexible economy has let it switch output towards exports, which have held up well despite the strong euro. Greece and Spain have no such cushion. They are likely to pay a high price for failure to reform their labour markets during the good years.

Insurers' Claim Rejections Multiplying Lenders' Pain

Private mortgage insurers have stepped up their rejections of claims on defaulted loans, compounding the pain that banks and other lenders have felt from the housing crisis. In the second and third quarters, insurers denied 20% to 25% of claims, up from a historic rate of 7%, according to Moody's Investors Service Inc. Though the insured party is usually Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, lenders that do business with the government-sponsored enterprises stand to lose when claims are rejected.

This is because, when insurers deny claims, they also rescind the policies. The mortgages in question typically have loan-to-value ratios above 80%, which means Fannie and Freddie cannot hold them without the insurance. So when insurers cancel policies, the GSEs in turn make lenders buy back the loans. "Buybacks are really the pink elephant on lenders' balance sheets that no one wants to talk about," said William Armstrong, the chief executive of Blueberry Systems LLC, a Greenwood Village, Colo., developer of software that captures data discrepancies to prevent repurchase requests.

Fannie and Freddie have already been forcing lenders for more than a year to repurchase greater numbers of faulty loans for reasons other than insurance rescissions. The spike in rescissions is accelerating this trend. Freddie said in its third-quarter financial report that servicers had repurchased $960 million of loans from it during the period, nearly double the amount a year earlier. Fannie does not disclose its volume of repurchase requests, but in its third quarter report, the GSE said that its repurchase requests have been increasing since the beginning of 2008, and that it expects them to remain high into next year.

Peter Pollini, a principal of the consumer finance group at Pricewaterhouse Coopers, said repurchasing a loan whose insurance has been rescinded hits the lender with a "double-whammy." "They have a nonperforming loan that has been brought onto the balance sheet, and they can't sell it, and they have to take the full risk on that loan," Pollini said.

Insurance rescissions and buybacks reflect the dramatic loosening of underwriting standards in the middle of the decade. "Certain product types were flawed the day they were made," said David Katkov, an executive vice president and chief business officer at PMI Group Inc. in Walnut Creek, Calif.

Most loans whose claims are denied have "multiple reasons why they failed," said Katkov, whose company is the second-largest private mortgage insurer as measured by insurance in force. For example, a borrower could have a low FICO score combined with a high loan-to-value ratio, no documentation of income and a questionable appraisal, he said. The combination of all those risk factors on the same loan would make it fall outside PMI guidelines. "How is that loan ever going to perform the way I priced it to perform?"

At PMI, "we're all about paying legitimate claims," Katkov said. "My policy is very explicit. If you went over here and did something that is black, and I said you need to do something that is white, I'm not going to be obligated for that loan."

But others say the mortgage insurers are incorporating rescissions into their business models, using claim denial to get through the crisis. "Lenders are not happy, and the consumers paid a premium for nothing," said Rhonda Orin, a managing partner at the Washington law firm Anderson Kill & Olick. "Lenders counted on private mortgage insurance when they made the loans, and now you have insurers saying the mere fact that a mortgage goes into default means the borrower gave false information, and they're rescinding the policy instead of paying the claim. We call that post-loss underwriting."

The seven private mortgage insurers have rejected $6 billion of claims since early 2008, Moody's said. During the same period, they paid out an aggregate $18 billion to $20 billion in claims. It is unclear how long rescission rates will remain at today's historically high level. Katkov said he is not prepared to say claims are near their peak. But he said the loans made during the middle of the decade, when now-discredited practices like not documenting borrower incomes prevailed, "are getting close to the end of their life." Claims on newer loans are more driven by economic fundamentals like job losses, he said. This suggests that future claims will be harder to deny, though Katkov would not forecast rescission rates.

Banks repurchased $7.1 billion of defaulted single-family loans from various investors in the third quarter, National Mortgage News has reported, up from $1.9 billion in the second quarter. JPMorgan Chase & Co. repurchased the most loans last quarter, $2.7 billion, the newspaper said, and Bank of America Corp. was No. 2, with $2.3 billion repurchased.

B of A did not return calls. Tom Kelly, a spokesman for JPMorgan Chase, said most of its buybacks were of loans from Government National Mortgage Association pools. Such loans are insured by government agencies like the Federal Housing Administration, a part of the Department of Housing and Urban Development. So bringing them back on the balance sheet did not affect JPMorgan Chase's reserves or chargeoffs, Kelly said. But there also is concern that the FHA, whose capital reserves have dwindled, could become more aggressive in rejecting claims.

"HUD is acting more and more like an insurer where, if they are faced with a potential loss, they will look at the file just like a mortgage insurer, and they won't pay the claim if there is a problem," said Dan Cutaia, the president of Fairway Independent Mortgage in Sun Prairie, Wis. "That's a big change because FHA has been pretty lax over the years." Laurence Platt, a partner at K&L Gates LLP, said lenders could take comfort that FHA has higher thresholds for claim rejections than private insurers, which can deny a claim if information is materially untrue. "FHA has to show the lender knew or reasonably should have known if information is incorrect," he said. "So the lender never bears the risk of pure borrower fraud unless it could reasonably have been caught."

Down-Payment Standards Eased

Some mortgage insurers and lenders are beginning to relax their down-payment requirements, in a sign of increased confidence in the housing market. The changes, which are being done on a market-by-market basis, mean buyers in some parts of the country can now borrow 95% instead of 90% of a property's value. Until recently, mortgage companies had tighter standards for these markets because of falling home prices. "We are feeling better about the economic condition of the marketplace," said Michael Zimmerman, senior vice president of investor relations at mortgage insurer MGIC Insurance Corp. Borrowers who want to finance more than 80% of a home's value must typically purchase mortgage insurance.

Earlier this month, MGIC removed New Orleans, Dover, Del., Akron, Ohio, and four other areas in Ohio from its list of restricted markets. The moves followed the company's decision in September to loosen restrictions on 11 markets, including Denver and St. Louis. Under the looser requirements, a borrower with a credit score of 680 or higher in New Orleans, for instance, can finance up to 95% of a home's value. Before the change, a borrower who wanted to finance that much of a home's value would have needed a credit score of at least 700.

In September, Genworth Financial Inc. winnowed its list of declining and distressed markets to five states: Arizona, California, Florida, Michigan and Nevada. That removed 63 markets from the list and followed an action in July that removed 136 other metro areas from the list. "We've seen some stabilization in the housing market," said Kevin Schneider, president of Genworth. While "additional home price declines" are likely, he added, tighter credit standards, including the requirement of full documentation and higher credit scores, should limit delinquencies.

Credit remains tight in some markets, such as Florida, because of concerns about additional home-price declines. Mortgage companies continue to closely scrutinize property appraisals, making it difficult for some borrowers to get financing. Amid persistent high unemployment, lenders and mortgage insurers are maintaining tough standards for credit scores, documentation and other measures of creditworthiness. In some cases, those standards are still getting tougher. Fannie Mae, the government-controlled mortgage company, last week raised its minimum credit score to 620 from 580.

But the latest moves, while modest, are an indication that some mortgage companies believe the worst home-price declines are over -- at least in certain parts of the country -- and that prices are likely to stabilize or fall slightly over the coming year. A rosier view of the housing market isn't the only factor driving the changes. Mortgage insurers also are seeking to regain market share from the Federal Housing Administration.

New insurance written by private mortgage insurers dropped by nearly 60% in the first nine months of 2009, compared with the same period a year ago, according to Inside Mortgage Finance. Borrowers without sufficient funds for a 20% down payment have been flocking to the FHA, which lends to people with as little as a 3.5% down payment. "To have any presence in the mortgage market, the mortgage insurers have to be more flexible," said Guy Cecala, editor of Inside Mortgage Finance, a trade publication. The mortgage insurers had gotten so strict, he noted, that their standards were tougher than those of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Meanwhile, some mortgage lenders are revisiting policies that were even tougher than those of the insurers. Wells Fargo & Co. executives met Friday for their quarterly review of market-based lending standards. For the first time since 2007, more markets will be moving to a less-risky status and lower down-payment requirements. Among those benefiting are parts of central California. Even in some of the country's most troubled markets, "we are starting to see...moderation" said Neil Librock, head of credit risk for the bank's home and consumer-finance group. Wells Fargo's changes could benefit borrowers the bank has been requiring to make down payments of more than 20%, he said.

New ice age for bankers

by Robert Peston

For all the furore about Alistair Darling's bonus super-tax, and for all the disclosure overnight by Deutsche Bank that it will spread the pain across all staff and shareholders around the world and not just in the UK, there is a much bigger threat to business-as-usual for banks and bankers.

The international rulemaking body for the banking industry, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, has proposed a series of reforms that would change the nature of banking in a profound way (Strengthening the resilience of the banking sector [282KB PDF]).

Some will mutter about stable doors and horses: it was the inadequacy of the existing Basel rules which provided dangerous incentives to banks to take the crazy risks that have mullered the global economy.

But be in no doubt. Although its reform paper, "Strengthening the resilience of the banking sector", may seem technical and obscure, it would turn a particular kind of high-paying, securities trading, global megabank - the institutions that created and defined the boom-and-bust conditions of the past decade - into an endangered species.

If I were running Barclays, or Deutsche Bank, or JP Morgan or even Goldman Sachs, I would be more than a little anxious about the cumulative impact of the Basel Committee's recommendations on the additional high-quality capital that banks would be required to hold, the liquid assets they need to accumulate and also - oh yes - the rewards banks can distribute to employees and shareholders.

Mr Darling's raid on their cash boxes looks trivial by comparison: it's just a one-off; Basel is forever.

The Basel reforms would make it prohibitively expensive for banks to do all that wheeling and dealing in securities and derivatives that yielded bumper profits and bonuses in the boom years and brought the world to the brink of depression last autumn.

Perhaps most significant would be the proposal to limit the ability of banks to pay out bonuses to staff and dividends to shareholders as and when their respective capital resources approach the minimum allowed.

The nightmare before Christmas for bankers is the tape on page 70 of the report, which sets out the new global incomes policy for them.

It will be seen by bank boards and owners as an infringement of their basic right to pay themselves what they want and when they want.

The consequences would be profound not only for the banking industry but also for the economy - which is why they will be phased in over years.

They are likely to mean that far less credit to households and non-financial businesses will be provided by conventional banks, because the cost to banks of providing credit in any form will rise.

They are also likely to force a mass exodus from banks of the more entrepreneurial, brainier, traders and financial engineers - who may either go for real jobs in the real economy (is that such a terrible idea?) or will create all manner of new-fangled financial institutions, which won't take retail deposits, won't be banks in a technical sense, and won't be subject to such onerous regulation and supervision.

Yes, the Basel plans almost certainly mean there'll be another great sprouting of hedge funds and alternative investment vehicles.

You can decide whether that's a good thing or a bad thing.

By the way, if you want a bit more granularity on how and why an ice age just arrived for banks and bankers, look no further than the recent Financial Services Authority discussion document on reinforcing the capital strength of British banks and also today's Financial Stability Report from the Bank of England [3.95Mb PDF].

The FSA estimates that financial institutions in the UK will need to raise an additional £33bn of capital to meet new rules out of the European Union designed to reduce the riskiness of their trading activities and of securitisation (of turning loans into tradeable assets).

Now the big point about that £33bn is that it does not include the additional requirements that will be imposed by the new Basel framework. The £33bn is just a beginning.

Which gives the banks two choices. They can try to raise the £33bn and whatever else is subsequently demanded of them. Or they can massively reduce their trading activities - which seems the more likely outcome.

Can they turn to the Bank of England for a shoulder to cry on. Not likely.

It makes this helpful point to banks which - it agrees - are still chronically short of capital: "reducing staff costs [at banks] by around one tenth and dividend payout rates by around a third would allow UK banks to increase retained reserves by close to £70bn over the next five years".

Crikey: five years of stunted bonuses! Grown bankers will weep.

Secrets strengthen case for CDS exchange

by Gillian Tett

Until recently, not many western politicians – let alone those in Greece – knew much about sovereign credit default swaps. Even fewer cared. But I suspect that is about to change. This year the CDS spreads on sovereign debt have swung sharply, as investors have turned to these products to hedge themselves against the danger of a government default (or quasi default). In the case of Greece, for example, the spread is currently about 240 basis points, compared with 5bp three years ago.

And since the CDS market is apt to be a leading indicator for other markets (just look, again, at the recent experience of Greece), the movement of spreads is starting to grab attention from investors and politicians alike. To many CDS fans, this is gratifying. After all, this rising focus on CDS supports the idea that these products are a useful part of the modern financial toolkit.

However, there could also be a sting in the tail for CDS lovers. As the level of attention grows, the level of regulatory and political scrutiny is likely to rise too. And if politicians do start paying more attention to the world of sovereign CDS – as they are likely to do if, say, more market turmoil erupts – there is a good chance that they could find things in this market that leave them perturbed. After all, one dirty secret of the sector is that trading volumes in the market are apt to be low, even in instruments that attract high attention (such as Greece or Dubai). Worse still, nobody really knows exactly how low volumes are (or not), because this is an over-the-counter market, conducted away from any exchange.

Thus even when spreads swing wildly on a sovereign name, it is hard to know whether that has arisen just because a big hedge fund has tried to move prices by conducting a huge trade – or whether there is truly a liquid market with sellers and buyers. Indeed, it is pretty tough for non-bankers even to get intraday prices for sovereign CDS (and though end-of-day quotes have recently become publicly available, these vary between data providers).

The pattern of investor demand also seems uneven. In the past year, plenty of investors have been buying protection against the chance of sovereign default. However, it appears that the main sellers of this protection are banks. That creates the perverse situation that (as the European Central Bank recently observed) European banks are now net sellers of insurance against the chance of their own governments going into default – even though those same banks are implicitly backed by those governments.

None of these problems, of course, is entirely unique to sovereign CDS; many other immature OTC markets are also pretty illiquid and opaque (and since sovereign CDS is just a few years old, it is still immature.) But what makes sovereign CDS so fascinating is politics. If prices swing wildly in opaque OTC equity derivatives products – or even CDS linked to small companies – politicians are unlikely to care.

However, if sovereign CDS start gyrating, and affecting government debt costs, that could create more controversy. Indeed, it already has: when the government of Iceland tipped into crisis last year, it was quick to claim that hedge funds were manipulating the price of Icelandic CDS.

Is there anything banks can do about this? Personally, I think the situation strengthens the case for moving some core corporate CDS indices on to an exchange, along with some sovereign CDS. After all – as one of the savviest Wall Street players recently pointed out to me – if you look at the other big four asset classes in the financial world today (namely equities, rates, foreign exchange and commodities) it is notable that all of those have transparent, credible benchmarks, to act as a "core", around which bespoke, more opaque, products can be built.

Credit markets, however, have developed without this, because although corporate indices such as the iTraxx are liquid, they are not as publicly credible and transparent as, say, the S&P 500, the gold price or dollar-yen rate. Now putting trading on an exchange is certainly not the only way to garner more investor credibility. But it is the easiest way to create a stronger "core" and protect the sector from political sniping too. And even if a small core of products were placed on an exchange, banks could still create bespoke products too, referencing that core.

Will this happen? Don’t hold your breath. Most large banks strongly oppose the idea of exchange trading for CDS; instead, they hope that improving the OTC infrastructure, by improving clearing platforms, will be enough.