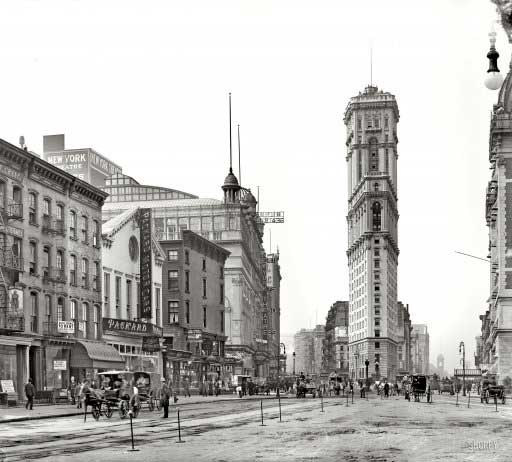

"Longacre Square, New York." Soon to be renamed Times Square after the recently completed New York Times tower seen here.

Ashvin Pandurangi:

(Revisiting The Limits to Complexity)

A little more than a year ago I wrote an article generally sketching out The Limits to Complexity that our global society faced back then and continues to face now. The speed at which some of these limits have materialized for the average consumer, business, investor, employee, taxpayer, politician and central banker in the developed world, while expected by many, has still been nothing short of flabbergasting.

Before revisiting the complex "solutions" formulated by governments and central banks to address the problem of over-complexity, we should briefly recap what has happened over the last decade and a half, more or less.

During and after the implosion of the "tech bubble" and the brief financial recession of the late 1990s, major banks and corporations around the world realized they needed a new "asset" which could be leveraged by consumers and businesses to support aggregate demand and, therefore, their revenues and profits.

With the help of aggressive fiscal policy, new government statutes (i.e. "Community Reinvestment Act"), the repeal of pesky "firewalls" ("Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act" repealing the "Glass-Steagall Act") and accommodating (low-interest) monetary policy, private banks pushed unfathomable amounts of debts onto people and businesses who could not afford them by any stretch of the collective imagination.

These same banks were also allowed to securitize many of the underlying loans, sell them off to various institutional investors and market derivative instruments to those clients who wished to gain exposure to the global sub-prime mortgage bonanza. When the greatest financial ponzi scheme known to man eventually collapsed in 2007-08 and it was clear that the global economy faced an imminent depression, governments worldwide decided to "respond".

What this response amounted to was an attempt to maintain economic and financial complexity by adding on layer after layer of ever-more complex structures, and suspending/manipulating any measure of reality that was in the least bit accurate.

Those layers, in part, took the form of unprecedented fiscal and monetary policy, which funneled trillions worth of taxpayer-guaranteed funds to banks that were deemed too complex too fail. So how did this big dose of complexity fare after the flames died down and the smoke cleared? Focusing on the U.S., here's what I wrote last year about Obama's $820B "American Reinvestment Recovery Act" (ARRA):

The Limits to Complexity"The [ARRA] allocated about $820 billion to various local governments and companies in an effort to create jobs. What they don’t tell you about the ARRA is how much of that money, as a matter of necessity, is wasted in bureaucratic institutions that distribute and keep track of the money as it is funneled down to economic actors. Much of the money also goes to funding extremely misguided projects, such as tax credits for homebuyers that incentivized the construction of new homes when there is already a year’s worth of excess supply.

Sometimes the money goes to fund the repair of roads that don’t even need any repair, as I have personally witnessed in my own community. New estimates have made clear that it is unlikely more than 1 million jobs were created by the ARRA stimulus, which amounts to $820,000 per job, some of which were not even productive for the general economy."

Despite the [misleading] BLS unemployment rate falling to 9.1% in 2011 (signifying more people who have given up looking for work), the employment situation has significantly deteriorated since last year. On Friday, the non-farm payroll numbers came in at +103K for the month of September, with about 40K of that coming from Verizon workers who ended their strike. The more accurate U-6 unemployment measure increased to 16.5%, its highest since December of 2010. Zero Hedge has calculated that at least ~261K jobs must be created every single month for the next five years for the unemployment rate to return to pre-2008 levels, and this number has been consistently increasing every time it performs the calculation. [1]

The number for August was revised upwards from ZERO jobs created to 54K, which is still an overall dismal print. Manufacturing jobs declined by 13K in the month of September, while average duration of unemployment hit an all time high of 40.5 weeks. [2]. Initial claims have continued to hover around 400k per week for at least the last six months (and have been consistently revised upwards), which essentially implies no jobs are being created. [3].

According to the non-farm payroll report for August 20111, ZERO jobs were created in that month, with the employment numbers for June and July both being revised downwards for a total reduction of about -60,000. An additional 600,000 people from last year were working part-time "for economic reasons" and were "marginally attached" to the labor force. [1]. Initial claims are still hovering around 400k per week for at least the last six months (consistently revised upwards), which essentially means no jobs are being created. [2].

It is quite clear, then, that Obama's stimulus did very little to spur job growth, and now he is facing an even bigger limit to complexity - a dearth of political capital to pass any new "jobs bills" through Congress. On the monetary front, policy mainly took the form of slashing the federal funds rate to near zero and launching asset purchase programs which targeted more than $2 trillion in mortgage-backed securities and Treasury notes/bonds over the last two years. As the principal on the MBS was paid down, that money was reinvested back into Treasuries (and now more MBS) to maintain the value of securities on the Fed's balance sheet.

The Limits to Complexity"The above policies serve to keep a floor on mortgage rates and finance our government’s deficits at low interest (what used to be stealth monetization is now just monetization), while also providing cash to banks with the alleged hope that they will lend it out into the economy, where consumers and businesses will spend/invest the loaned money. Out there in the real world, no such lending has happened, as the banks are sitting on $1+ trillion in cash and the Fed is caught in a liquidity trap.

[..] Private markets are currently saturated with debt and therefore very few people want to borrow money, and very few lenders want to make loans at affordable rates since debtors can barely pay back what they owe now. As mentioned before, interest rates have bottomed out and there is minimal economic activity to show for it. The velocity of money in the economy has collapsed, and the Fed’s policies merely transfer large sums of taxpayer money to major banks that use it to blow more speculative bubbles in stocks, bonds, commodities, and derivative bets on the price movements of those assets."

Since the time that was written, we have seen numerous destructive consequences derived from this monetary policy. The speculative bubbles mentioned above have led to soaring inflation in the Middle East, which, in turn, has been partly responsible for the ensuing sociopolitical unrest and violence. At the same time, global markets are largely back to the same valuations they were at a year ago when QE2 was implemented.

Banks are now sitting on at least $600 billion of additional cash (excess reserves deposited at the Fed). [3]. Back then, I also mentioned that "equity outflows from institutional investing firms have continued for months unabated and have totaled over $50 billion year-to-date". Well, let's go ahead and make that a four-fold increase to $200 billion in the last two years. [4].

And since the Fall of 2010 is so out of style and the Fed does not currently have enough credibility to launch a similar asset purchase program, it has decided to merely shift the duration of Treasuries on its portfolio (swapping $400 billion in short-term bills/notes for $400 billion in longer-term bonds).

This "twist" operation has done absolutely nothing to spark appetite for risk and is actually perceived as being net negative for financial markets, since long-term rates will compress and the yield curve will be flattened even further, thereby limiting the ability of banks to generate profits from interest spreads. Another limit to complexity, perhaps?

Ben Bernanke has consistently punted the responsibility for supporting "confidence" in markets and the economy to the Administration and Congress in recent months, and they consistently prove to us that they are both politically and financially unable and unwilling to do anything meaningful for neither one nor the other.

Central authorities in the West have exhausted almost all of their tools for supporting financial markets, except for increasingly short-term liquidity measures. In addition, the policies they have enacted in the comfort of 2010 are now coming back to haunt them, as the publicly-sponsored complexity has made the system even more inflexible than it was before.

This layered complexity also took the form of Western governments placing an item misleadingly known as "financial reform" on their political agendas. In the U.S., "financial reform" amounted to federal politicians attempting to somehow regulate systemic financial stability into existence by creating a few new government agencies or sub-agency departments, which possessed a few more monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, and A LOT more bureaucracy.

These agencies were essentially tasked with monitoring "systemic developments" in the financial sector whenever they felt up to the task. I wrote the following about this issue soon after the Dodd-Frank bill had been passed into law:

The Limits to Complexity"[..] and the "finreg" bill failed to break up the TBTF banks, audit the Fed or create transparency for risky derivative products. More importantly, these new top-down regulations have the inherent feature of creating unintended consequences in our complex society, despite the alleged best intentions of their creators, and can even make the targeted problem worse.

The financial reform bill created new restrictions on "angel investors" which will inadvertently stymie the creation/expansion of small businesses, while the behemoth investment banks will continue to exploit financial markets by hiring teams of lawyers to easily bypass the new regulations that affect them (as they are currently doing with the "Volcker Rule") or by simply buying off the regulators."

Fast forward to today and we can clearly see that not a single soul on Earth, let alone those moving the markets, believe the Dodd-Frank Bill did anything to mitigate systemic risk or even make sure it could be adequately identified before developing into another full-blown crisis (which has already begun). And then, of course, we have the unintended consequences of complexity.

One major unintended consequence of the Dodd-Frank Bill that has recently asserted itself stems from the "Durbin Amendment" (introduced by Congressman Dick Durbin-D-Ill). What analysts are now labeling the "Durbin Tax" provides us with the quintessential example of diminishing returns to complexity. Forbes Magazine reports:

Bank of America Debit Card Fees Slammed as "Durbin Tax"The law applies to those big banks – the ones over $10 billion in assets – and was ostensibly passed as an effort to increase competition. It was supposed to be pro-consumer.

But here’s the kicker: the Amendment gave the Federal Reserve the power to regulate debit card interchange fees and other bits of banking admin, which they’ve done. Over the summer, the Fed released the final rule on the matter. The combination of fees, restrictions and caps is thought to cost banks subject to the amendment nearly $14 billion annually.

The banks could try to recoup this money from somewhere else – like merchants. But merchants now have the ability to shop around a bit more and of course, they could refuse to accept cards altogether. It was quicker, cheaper and easier for banks to go straight to the customer.

Forbes Magazine is simply a shill for the big banksters, but the underlying point remains true. When politicians attempt to regulate "financial consumer protection" into existence by layering on increasingly complex regulations, they are bound to create unintended situations such as this one. They are also bound to not even recognize that these consequences have occurred. That is why Congressman Durbin can create legislation that has forced banks to impose fees on their customers, and then stand on the floor of Congress a little over one year later and tell those same customers to "get the heck out of" Bank of America, because it had the nerve to impose a debit card usage fee!

It's not just Bank of America either, but Citigroup, Wells Fargo and JP Morgan who are also proposing to institute debit card usage fees on their customers. For the time being, people will put up with this extortion because they see no other convenient places to park their cash or ways to make their purchases and pay their bills.

Rest assured, though, that these measures are a sign of desperation by the major banks, and will eventually lead to much fewer commercial transactions by consumers, which will dampen economic growth and decimate the profit margins of banks even further. Of course, the limits to complexity are not only present in the U.S. financial system, but the entire global economy, as Europe, China, Japan, Canada, Australia and many other "emerging economies" can attest to.

Just last year, many of these regions were being hailed by mainstream analysts as survivors of the "Great Recession" and the future drivers of global economic growth. Now, their FIRE sectors are imploding and they are all following the U.S. and Europe down the swirling contours of the collective toilet bowl.

The financial topic du jour is, and has been for many months now, the critical situation in the EMU. At this point, there is very little need to even point out the limits to the EMU’s complexity. One clear example, though, is the most recent discussions about the size and nature of the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF).

It was only a few weeks ago that the European leaders were discussing possibilities of expanding and/or "leveraging" the fund to adequately backstop the public financing needs of Italy and Spain, and prevent contagion from a Greek default. Today, some pundits and politicians are discussing whether the fund should instead be used to directly recapitalize Euro-area banks that are struggling to stay solvent. Stephen Castle reports for the New York Times:

Europe Calls for Infusion of Capital for BanksIf Europe did adopt a regionwide approach to recapitalizing the banks, the question is whether that money would come from the bailout fund agreed to in July, which must still be voted on by a handful of member nations. If adopted, as expected, that bailout fund — the European Financial Stability Facility — would gain an effective lending capacity of 440 billion euros ($595.4 billion).

That might be enough to provide the necessary capital cushion to the region’s banks. But it would leave little cash to lend to any national governments that might require aid to protect themselves from a Greek contagion. Spain and Italy are seen most vulnerable on that count.

Needless to say, there is bitter political disagreement on both of those issues and it is looking very unlikely that either will be done anytime soon, when the countries and banks need it the most to survive in their current form. [6]. Financially speaking, it is simply impossible for France and Germany to backstop the entire Euro periphery OR major Euro-area banks, let alone both of them.

That fact becomes even more poignant when we consider another brutal limit to complexity in the form of France being downgraded by ratings agencies if it decides to bail out all of these other institutions. That would place enormous pressures on its own sovereign financing situation and effectively make it a non-factor in the bailout mechanisms.

Stephen Castle once more:

"France’s caution over recapitalization illustrates how each potential solution to the euro zone crisis tends to become entangled in member nations’ domestic politics. A downgrade of France’s debt rating would be damaging to the French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, ahead of presidential elections next year.

The problem is that if you recapitalize the banks, then you have a problem with sovereign debt," said one European official not authorized to speak publicly. "That is Paris’s big issue."

Sarkozy and Merkel are hashing it today (Sunday) to see if they can agree on just how badly the Western taxpayers will be shafted yet again. Paris has suggested to use the very recently expanded "stabilization fund", created to backstop sovereign bonds, and redirect much of it towards recapitalizing banks directly. Berlin has said so far that this is a ridiculous proposal and the fund is only to be used as a "last resort" for the banks. [7]. Although Dexia, the Belgian bank that scored highest on the EU "stress test" earlier in the year and was the first to implode, has once again reminded us that the banks' first resort is the same as their second resort and every other resort up until their last resort: taxpayer-funded bailouts.

The problem for the panhandling elites is that these bailouts are not as simple and as much of a given as they used to be, which was evident in the decision over whether to bail out Dexia and to what extent. The bailout issue was finally “resolved” today as France and Belgium agreed to nationalize 100% of Dexia’s operations, which is 100% against the interests of Belgian and French taxpayers. The plan must still be submitted to Dexia’s Board of Directors, who are sure to approve of any public bailout they can get their greedy hands on. Reuters reports:

France, Belgium, Luxembourg agree Dexia Rescue"The burden of bailing out Dexia led ratings agency Moody's to warn Belgium late on Friday that its Aa1 government bond ratings may fall.

The negotiations to dismantle Dexia, which has global credit risk exposure of $700 billion -- more than twice Greece's GDP -- are being watched closely for signs that Europe might be capable of decisive action to resolve its banking crisis. "I am convinced that it is possible ... by tomorrow morning to have an agreement in which Belgium resolves the issue without pushing up the debt level of our country too high," Leterme told Belgian television before the talks began on Sunday.”

It’s not that Belgium may be downgraded, but that it will be downgraded if the deal goes through, and France’s ratings may come under some pressure as well. No matter what happens, Dexia is just the first of many European banks to pass the faux “stress tests” with flying colors and subsequently implode within months, including major French banks. When those banks reach the edge of bankruptcy and need a public bailout, there is no way France will come out of that with their AAA bond rating intact, and a French downgrade will feed into the need for even more bailouts. Since the implosion of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers nearly three years ago, nothing has changed. The limits to complexity have been stretched out a bit, but now they are well poised to snap back even harder.

It turns out that everyone who participated in the mainstream dialogue had bought into the narrative of a global economic "recovery" and had conditioned their policies and attitudes accordingly. Now, they are all left reeling from the strict, unflinching evolution of complex systems. The subject of "bailing out banks", which was too taboo to even discuss last year, is now priority #1 on the policy agenda in Europe (and will soon be in the U.S.), but there is simply not enough political or financial capital left to do the job.

Soon, the global financial system will be forced to revisit the limits to complexity, just as we have done today, and this time it will not be so easy for our leaders to avoid their implications.

Ilargi: Here's a global map of Occupy groups, as well as info on the one closest to you. There are now groups in 1200 cities(!). See here for more. You can also set up your own group there.

I have a lot of sympathy for the Occupy movement, but at the same time I fear for it. Seeing the faces of both Michael Moore and Glenn Beck (not to mention Nancy Bleeping Pelosi: she supports you, you're cooked) pop up in the same places will do that for me. All sorts of people attempting to ride the Occupy wave for personal gain and purposes is a huge risk. As is infiltration.

As I wrote earlier this week in Occupy This: Mark the Banks to Market, I think that in many instances, demanding that politicians mark all bank assets to market before any kind of financial support is given to banks, is one of the best, if not the best, period, goal to aim for.

Protesting bankers' greed is useless; bankers can only do what the political systems lets them, and as long as the system allows them to feed their greed, they will. So what protests should be targeted at is to change the political side of the equation. If the movement fails to understand this, it is destined for complete and utter failure. And that would be a bitter shame. It would also be exactly what those people want whom the movement agitates against. Be careful out there, guys!

The map for all Occupy groups and meetings in the world:

And the one nearest your location:

Ilargi: Update: I see a headline float by just now from the Telegraph that about perfectly grasps the "nonsenseness" of Nicolas Sarkozy's claim that he's sure the euro crisis will be over before the end of the month.

Nicolas Sarkozy and Angela Merkel set a date to save Europe

Sarkozy really said it. Why these people say such things, and what they are thinking, G-d only knows. What's he going to say on November 1 when everyone can see there's no such thing as the crisis being over? Who's he going to blame for it? And besides, if you know how to solve the crisis, there's no time like the present, right?!

Fitch Predicts Half of All US Prime Mortgages Will be Underwater

by NationalMortgageProfessional.com

The sputtering U.S. housing market will result in more prime borrowers being pushed further underwater on their mortgages, according to Fitch Ratings in a new report. Recent analysis by Fitch shows that more than 30 percent of all prime borrowers in private-label securitizations are currently in a negative equity position on their mortgages.

"With home prices likely to decline another 10 percent, roughly half of prime borrowers will wind up underwater on their mortgage," said Managing Director Grant Bailey. Fitch also found over 12 percent of all prime borrowers are seriously delinquent on their mortgages. "Prime mortgage default rates will stay elevated as home prices fall further and unemployment remains high," said Bailey.

The combination of declining equity, rising delinquencies, growing payment shock risk and the application of Fitch's updated criteria led to further negative rating actions on prime residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) transactions in Fitch's latest ratings review. While Fitch either affirmed or upgraded 58 percent of prime RMBS ratings, 42 percent of prime RMBS ratings, primarily those already rated 'B' or below, were downgraded further by Fitch. Further, approximately 97 percent of investment-grade classes that Fitch downgraded were already on Rating Watch Negative prior to the rating revision.

Fitch has cited borrower equity as the pre-eminent driver of mortgage default performance in its new rating model. The number of underwater borrowers is likely to increase over time. With this latest rating review now complete, however, the application of Fitch's new criteria should result in greater rating stability going forward.

IMF advisor says we face a Worldwide Banking Meltdown

"If they can not address [the financial crisis] in a credible way I believe within perhaps 2 to 3 weeks we will have a meltdown in sovereign debt which will produce a meltdown across the European banking system.

We are not just talking about a relatively small Belgian bank, we are talking about the largest banks in the world, the largest banks in Germany, the largest banks in France, that will spread to the United Kingdom, it will spread everywhere because the global financial system is so interconnected. All those banks are counterparties to every significant bank in the United States, and in Britain, and in Japan, and around the world.

This would be a crisis that would be in my view more serious than the crisis in 2008.... What we don't know the state of credit default swaps held by banks against sovereign debt and against European banks, nor do we know the state of CDS held by British banks, nor are we certain of how certain the exposure of British banks is to the Ireland sovereign debt problems."

France, Belgium and Luxembourg agree Dexia deal

by Reuters

France, Belgium and Luxembourg said on Sunday that they had reached a deal to dismantle troubled bank Dexia, the first victim of the eurozone debt crisis. In a joint statement, the three countries said, "The proposed solution, which is the result of intensive consultations between all involved parties, will be submitted to the Dexia board, whose responsibility it is to approve the plan."

French and Belgian prime ministers, Francois Fillon and Yves Leterme, held a lunch-time meeting to finalise the deal to dismantle the bank, which also had to be rescued in 2008 at the start of the global financial crisis. Leterme said he hoped that Dexia's board of directors which met at 2pm BST would rapidly approve the deal. He said a final solution to the Dexia crisis "depends on the board", Belga news agency reported.

France and Belgium, Dexia shareholders after the 2008 bailout, needed to agree on the sale price of Dexia shares, including in its Belgian retail banking arm Dexia Bank Belgium that Brussels wants to buy. They also needed to agree on the guarantees backing up a so-called "bad bank" that will remain after Dexia's dismantling to hold high-risk assets.

After the Dexia board meeting key members of Leterme's cabinet were to convene later Sunday to give their blessing to the deal of which no details were immediately known. The three governments involved, who are keen to finalise a deal before stock markets open on Monday, said they were working together to "search for a solution that will secure Dexia's future".

The NYSE Euronext stock exchange suspended trading in Dexia shares on Thursday following a request of the Belgian market regulator, FSMA. Trading in the stock was halted during a session in which it had fallen 17.24pc to €0.85 per share.

The bank's woes were to figure highly during a summit by the leaders of France and Germany, the eurozone's top economies, in Berlin where Chancellor Angela Merkel and President Nicolas Sarkozy will try to find common ground on a plan to recapitalise banks amid rampant fears of a credit crunch.

France and Belgium, who were forced last week to step in and rescue Dexia, are in disagreement over the price for Dexia Bank Belgium, which the Belgian state now wants to buy, according to media reports. Credit ratings agency Moody's also warned on Friday that Belgium could be downgraded over its support for Dexia.

Moody’s places Belgium’s Aa1 ratings on review for possible downgrade

by AP

Moody’s Investors Service is placing Belgium’s Aa1 ratings on review for possible downgrade, as the country appears to be on the verge of paying a significant amount of money to prop up the French-Belgian Dexia bank.

In a statement late Friday, the ratings agency said the review was prompted by the increase in long-term funding risks for euro area countries with high levels of public debt, the risk that the debt will increase because of poor economic growth, and "the uncertainty around the impact on the already pressured balance sheet of the government of additional bank support measures which are likely to be needed."

After Dexia’s shares tanked this week amid fears it could go bankrupt, the French and Belgian governments stepped in and guaranteed its financing and deposits.

Fitch downgrades Italian and Spanish debt ratings

by Nicole Winfield - AP

The Fitch agency downgraded its sovereign credit rating for Italy and Spain today and said its long-term outlook for both countries was negative, citing high debt and poor prospects for growth.

Separately, Fitch also said it was keeping Portugal's debt rating on watch for a possible downgrade, with a decision due by the end of the year. Portugal was the third and latest eurozone country to receive an international bailout package after Greece and Ireland. Fellow ratings agency Moody's warned on Friday night that it has put Belgium on watch for a possible downgrade.

The reports are a blow to Europe's hopes of containing the debt crisis that has already seen three countries bailed out. Italy and Spain have the eurozone's third- and fourth-largest economies and are widely considered too expensive to rescue. Fitch downgraded Italy's creditworthiness from AA- to A+, citing high public debt, low growth and the "politically technical and complex" solution necessary to fix Italy's financial ills and earn back the trust of investors.

While saying Italy's recent austerity measures improved its standing, "the initially hesitant response by the Italian government to the spread of contagion has also eroded market confidence in its capacity to effectively navigate Italy through the Eurozone crisis," Fitch said.

The move came after Moody's Investors Service on Tuesday downgraded Italy's bond ratings to A2 with a negative outlook from Aa2. On September 19, Standard & Poor's cut Italy's long- and short-term sovereign credit ratings one notch, though its rating is still five steps above junk status. Despite the downgrade, Fitch said Italy's sovereign credit profile remains "relatively strong" and that its budget position compares favorably to other European countries.

Also Friday, Fitch cut Spain's sovereign debt rating by two notches to AA- from AA+, citing increased risks from the eurozone financial crisis as well as high debt in regional governments and weakening growth prospects. Like Italy, Fitch kept a negative outlook on Spain, but said it expected the country to remain solvent. It says that debt reduction efforts will weigh on growth and keep unemployment high. Spain currently has the eurozone's highest jobless rate at over 20pc.

It said more reforms will be necessary to make Spain's economy more competitive, particularly in the labor market, and that another €30 billion (£25.9 billion) may be needed to recapitalize the country's weaker banks. Banks across Europe are under pressure in markets because of investor fears that they could take heavy losses on government debt they own.

The agency said the debt crisis - which has seen financial markets drop severely on worries that some governments, particularly Greece, will be unable to repay all their borrowings - will take time to fix.

'The Greatest Threat to Europe Is the Bailout Fund'

by Maria Marquart - Spiegel

Only two countries, Malta and Slovakia, have yet to ratify the expansion of the euro bailout fund. Its fate may be in the hands of a minor Slovak party headed by Richard Sulik. In an interview, the politician explains why he hopes the fund will fail and what he sees as the only way to save the euro.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: Mr. Sulik, do you want to go down in European Union history as the man who destroyed the euro?

Richard Sulik : No. Where did you get that idea?

SPIEGEL ONLINE: Slovakia has yet to approve the expansion of the euro backstop fund, the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), because your Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) party is blocking the reform. If a majority of Slovak parliamentarians don't support the EFSF expansion, it could ultimately mean the end of the common currency.

Sulik: The opposite is actually the case. The greatest threat to the euro is the bailout fund itself.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: How so?

Sulik: It's an attempt to use fresh debt to solve the debt crisis. That will never work. But, for me, the main issue is protecting the money of Slovak taxpayers. We're supposed to contribute the largest share of the bailout fund measured in terms of economic strength. That's unacceptable.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: That sounds almost nationalist. But, at the same time, you've had what might be considered an ideal European career. When you were 12, you came to Germany and attended school and university here. After the Cold War ended, you returned home to help build up your homeland. Do you care nothing about European solidarity?

Sulik: If we now choose to follow our own path, the solidarity of the others will also crumble. And that would be for the best. Once that happens, we would finally stop with all this debt nonsense. Continuously taking on more debts hurts the euro. Every country has to help itself. That's very easy; one just has to make it happen.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: Slovakia's parliament is scheduled to vote on the bailout fund expansion on Oct. 11. How do you predict the vote will turn out?

Sulik: It's still open. The ruling coalition is composed of four parties. My party will vote "no"; the other three coalition parties intend to say "yes." What the opposition says is decisive.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: The Social Democrats have offered your coalition partners to support the reform in return for new elections. Do you think the coalition is in danger of collapse?

Sulik: I don't see any reason why it would.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: What will you do should the EFSF reform pass despite your opposition?

Sulik: For Slovakia, it would be best not to join the bailout fund. Our membership in the euro zone, after all, was not conditional on us becoming members of strange associations like the EFSF, which damage the currency.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: If the euro only causes problems, why doesn't Slovakia's government just pull the country out of the euro zone?

Sulik: I don't see the euro as the problem. It's a good project. Everyone involved can benefit from it -- but only if they stick to the ground rules. And that's exactly what we're demanding.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: Which ground rules should we be following?

Sulik: We have to observe three points: First, we have to strictly adhere to the existing rules, such as not being liable for others' debts, just as it's spelled out in Article 125 of the Lisbon Treaty. Second, we have to let Greece go bankrupt and have the banks involved in the debt-restructuring. The creditors will have to relinquish 50 to perhaps 70 percent of their claims. So far, the agreements on that have been a joke. Third, we have to be adamant about cost-cutting and manage budgets in a responsible way.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: Many experts fear that a conflagration would break out across Europe should Greece go bankrupt and that the crisis will spill over into other countries, including Portugal, Spain and Italy.

Sulik: Politicians can't allow themselves to be pressured by the financial markets. Just because equity prices fall and the euro loses value against the dollar is no reason for giving in to panic.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: But do you really believe that politicians can calm the financial markets by stubbornly sticking to their principles?

Sulik: Let's just ignore the markets. It's ridiculous how politicians orient themselves based on whether stock prices rise or fall a few percentage points.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: You're not afraid that a Greek insolvency could mark the beginning of the crisis instead of the end?

Sulik: No. There's not going to be a domino effect along the lines of "first Greece, then Portugal and finally Italy." Just because one country goes broke doesn't mean the other ones automatically will.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: Nevertheless, banks could run into significant problems should they be forced to write down billions in sovereign bond holdings.

Sulik: So what? They took on too much risk. That one might go broke as a consequence of bad decisions is just part of the market economy. Of course, states have to protect the savings of their populations. But that's much cheaper than bailing banks out. And that, in turn, is much cheaper than bailing entire states out.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: Does one of your reasons for not wanting to help Greece have to do with the fact that Slovakia itself is one of the poorest countries in the EU?

Sulík: A few years back, we survived an economic crisis. With great effort and tough reforms, we put it behind us. Today, Slovakia has the lowest average salaries in the euro zone. How am I supposed to explain to people that they are going to have to pay a higher value-added tax (VAT) so that Greeks can get pensions three times as high as the ones in Slovakia?

SPIEGEL ONLINE: What can the Greeks learn from the reforms carried out in Slovakia?

Sulik: They have to make cuts in the state apparatus. The Slovaks could also give them a few good ideas about the tax system. We have a flat tax when it comes to income taxes. Our tax system is simple and clear.

SPIEGEL ONLINE: One last time: Do you honestly believe the euro has any future at all?

Sulík: I believe the euro has a future. But only if the rules are followed.

Slovaks May Hold Key to Euro Debt Bailout

by Nicholas Kulish - New York Times

In a television advertisement for the popular Slovak beer Zlaty Bazant, a grinning man with a paunch stands on a sunny beach, nodding his head as the narrator says, "To want to borrow from everyone, that is Greek." The ad then cuts to a skinny man, standing in a field, who shakes his head. "To not want to lend to anyone," the narrator says, "that is Slovak."

The commercial has touched a nerve here in the second-poorest country in the euro currency zone, where the average worker earns just over $1,000 a month. The prospect of guaranteeing the debt of richer but more spendthrift countries like Greece, Portugal and even Italy has led to public outrage. So much so that tiny Slovakia now threatens to derail a collective European bailout fund to shore up the euro, which requires the approval of all 17 countries that use the currency.

Once among the most enthusiastic new members of the European Union, and an early adopter of the euro in Eastern Europe, Slovakia is proud of its strong growth and eager to leave behind its reputation as the "other half" of Czechoslovakia. But it has also become a stark example of the love-hate relationship that many residents of the Continent have begun to feel toward a united Europe.

Adopting the euro required hard sacrifices here that stand in sharp contrast to reports of overspending and mismanagement in Greece. The worries about the union’s future are all too real in smaller, poorer countries like Slovakia, which has about 5.5 million people, and is being asked to contribute $10 billion in debt guarantees to a $590 billion euro zone stability fund.

Not far from the new malls and hotels along the River Danube is Trhovisko Mileticova, a market dating from Communist times, where pensioners search for bargains among the barrels of pickled vegetables and cheap synthetic blouses from Asia. "It’s tough to get by with euros," said Zuzana Kerakova, 64, who sells grapes at the market to supplement the combined 600 euros — about $804 — that she and her husband receive from a government pension every month.

Like many here on a recent morning, Ms. Kerakova said there always seemed to be enough money to help banks and foreign states but never people like her. On the other hand, she said: "The European Union has been good to us. We live more freely, move more freely." Asked whether to side with Europe or refuse to help with the bailout fund, she said quietly, "Neviem," Slovak for "I don’t know." "Neviem," she repeated, shaking her head. "Neviem."

The future of the euro could well be decided next week in the Slovak Parliament, which meets in a modern building that is too small to hold offices for all its members and their staff because it was originally designed to hold only occasional sessions of Czechoslovakia’s Federal Assembly, which usually met in Prague. The Parliament building overlooks not only the Danube but also the former frontier of the Iron Curtain, which cut off Bratislava from Vienna, less than an hour’s drive upriver and the cold war gateway to the free world.

The expansion of the bailout fund is in danger because the free-market Freedom and Solidarity Party, just one member of the four-party governing coalition, has held out against it. "I am not the savior of the world," Richard Sulik, who is both the party’s leader and the speaker of Parliament, said in a recent interview here. "I was elected to defend the interests of Slovak voters."

The opposition Smer-Social Democracy party could bridge the gap, but its leader, the leftist former Premier Robert Fico, hopes to bring down the government and win new elections, paving the way for his return to power, and is holding out for the coalition to crack.

The situation in Slovakia illustrates how ambitious young politicians, outspoken populists and struggling small parties can hinder collective action — or even derail it. Even if a compromise is found here, as it was in Finland, by the time agreement is reached among all 17 countries, investors will have long since moved on to a new batch of fears.

The vote over the expansion of the bailout fund, the European Financial Stability Facility, and its powers, is only one step. "The E.F.S.F. is not the end of the story. We will need to have other solutions," said Slovakia’s finance minister, Ivan Miklos. "This is the dilemma. Everyone agrees that we need more flexibility."

Slovakia’s relationship with the European Union runs far deeper than a single debt crisis or bailout. In the 18 years since independence, few countries have experienced such unusual twists of fate and fortune. From the "black hole in the heart of Europe," as Madeleine K. Albright described the backward, isolated state in 1997, the country transformed itself into a neoliberal champion of the flat tax.

With automobile factories springing up across the country, it earned the nickname the Detroit of Europe. It is also called the Tatra Tiger, a name derived from a local mountain range, because of its rapid growth, including the 10.5 percent economic growth rate it reported in 2007, just a decade after Ms. Albright’s dire pronouncement.

But perhaps Slovakia’s greatest sense of accomplishment came from beating its former partners, the Czechs; its former rulers, the Hungarians; and its larger neighbor, Poland, into joining the euro currency zone. Many Slovaks are reluctant to be the stumbling block for the euro’s rescue after all the European Union has done for them.

"Thanks to joining the European Union and the prospect of joining the euro zone, investors were more likely to show interest here," said Mayor Vladimir Butko of Trnava, a city about 35 miles east of the capital where a car factory produces Citroens and Peugeots.

The European Union helped to pay for improvements to the rail link to Bratislava, Mr. Butko said, and for a highway bypass. But he ranked the psychological benefits of European Union membership even higher than the economic ones. "When you can now sit in your car and go to Munich, and the same money in your pocket here can pay for a beer there, and you don’t have to stop at the borders," said Mr. Butko, 56, "this is a very strong experience for people over 45."

It is an experience that makes far less of an impression on the younger generation. Sebastian Petic, 18, a law student in Trnava who was spending a sunny afternoon on a bench in the town square with his Lenovo laptop, repeated a popular joke. "For 500 euro, you can adopt a Greek. He will sleep late, drink coffee, have lunch and take a siesta," Mr. Petic said, "so that you can work."

He opposed increasing the bailout fund, saying that debt would only snowball. "I was quite positive about the advent of the euro," Mr. Petic said. "Now, I’m not so sure."

17 Countries, but Even More Unknowns: What Investors Don’t Know About Europe

by Gretchen Morgenson - New York Times

"The direct exposure of the U.S. financial system to the countries under the most pressure in Europe is very modest."

That’s what Timothy F. Geithner, the Treasury secretary, told Congress last week, trying to allay concerns that American banks might be hurt by the escalating crisis in Europe. Investors have heard such assurances before, and they have learned to take them with a barrel of salt. Remember how the subprime crisis was going to be "contained"?

As the situation in Europe deteriorates, our own financial institutions are coming under growing scrutiny from investors. American banks have made loans to European ones. Some have also written credit insurance on the debt of European institutions and troubled nations like Greece. So if a default were to occur, some banks here would be on the hook.

Last week, officials at Morgan Stanley worked overtime trying to calm investors about the bank’s exposure to Europe. The company had $39 billion in exposure to French banks at the end of last year, not counting hedges and collateral. (Some analysts argue that the amount today is far lower, and at the end of the week, Morgan Stanley appeared to have relieved investor fears.)

Whatever the case, American banks have been writing more credit insurance lately. As of the end of June, some 34 federally insured commercial banks had sold a total of $7.5 trillion of credit protection, on a notional basis, according to the Comptroller of the Currency. That was up 2.3 percent from the end of March. To be sure, these figures represent the total amount of insurance written and do not reflect other offsetting trades that bring down these banks’ actual exposure significantly.

For investors, the challenges in trying to assess the true exposures are real. Many of the risks in these institutions are maddeningly hard to plumb, and open to a range of interpretations. The fact is, investors must deal with significant gaps in the data when trying to analyze a bank’s exposure to credit default swaps. Even the people who set accounting rules disagree on how these risks should be documented in company financial statements.

A recent report by the Bank for International Settlements noted: "Valuations for many products will differ across institutions, especially for complex derivatives which may not trade on a regular basis. In such cases, two counterparties may submit differing valuations for valid reasons." Investors, therefore, have to trust that the institutions are being appropriately rigorous.

To compute the fair value of derivatives contracts, financial institutions estimate the present value of the future cash flows associated with the contract. On this part, everyone agrees. But there are two subsequent steps in the valuation exercise that can produce wide variations on an identical exposure. First is the manner in which an institution offsets its winning and losing derivatives trades to come up with a so-called net exposure.

Accounting rule makers disagree about the right way to approach this process. Standard setters in the United States allow an institution to survey all the contracts it has with a trading partner and compute exposure as the difference between winning trades and losing ones.

International standard setters have taken a different view. They have concluded that investors are better served by knowing the gross figures of all of an institution’s trades, both the profitable ones and the money losers. Those favoring this approach say it gives investors more information and greater insight into the risks on the books, like how concentrated the bank’s bets are.

A recent report from the Bank for International Settlements illustrates how different the exposures can be, depending on which approach is used. Posing three hypothetical examples, the report noted that while the gross values of various derivatives totaled $41, the same trades dropped to $17 after netting, as is allowed in the United States.

The second area where investors must rely on institutions to do the right thing involves the collateral that has been supplied to secure derivatives contracts. Banks reduce their exposure to a possible loss by the amount of collateral they have collected from a trading partner. But is the collateral solid? Is the bank valuing it properly? Can it be located quickly? This, again, is a gray area.

The B.I.S., in its most recent quarterly review, highlighted these challenges. It said that gleaning information about collateral was difficult, and that arriving at a proper valuation was, too.

Further problems arise when it comes time to pay off a bet in a bankruptcy and close out one of these trades. At such a moment, liquidating collateral can put pressure on other positions carried by an institution, the B.I.S. noted. It is unclear whether institutions’ portfolio and collateral valuations reflect this reality.

Some investors who have been worrying about potential losses associated with European banks may have taken comfort in the results of financial stress tests conducted earlier this year by the Committee of European Banking Supervisors. Of the 91 top European banks tested — accounting for 65 percent of bank assets — only seven failed the toughest measures.

But, as an August report by Dun & Bradstreet pointed out, these tests were not as stringent as they might have been. They only assessed the risks posed by deteriorating assets in banks’ trading accounts. The tests did not measure those assets carried in the so-called held-to-maturity accounts.

"In order to give a more adequate picture of European financial sector risk beyond the short term," Dun & Bradstreet said, "we believe the hold-to-maturity bonds should have been included in the stress tests." There is clearly a great deal that investors do not know about exposures to Europe, notwithstanding the assurances from Mr. Geithner and others.

Three years ago, investors were ignorant of the risks in faulty mortgage securities. If we’ve learned anything from that episode, it’s that what you don’t know can, in fact, hurt you.

Bailouts or Bankruptcies?: Europe Begins Working on Plan B for the Euro

by Stefan Kaiser - Spiegel

How should the euro zone solve its currency crisis? European capitals are currently preparing to inject fresh capital into their banks with some economists arguing that saving financial institutions would be cheaper than propping up entire countries.

How much longer will the euro zone be patient with Greece? A growing number of politicians and economic experts are criticizing the rescue packages for the overly indebted nation and are instead demanding that Greece be allowed to slide into insolvency. Paris and Berlin continue to hold back. But, to be on the safe side, they are already preparing their domestic banks for a possible Greek default.

On Tuesday, European Union finance ministers discussed plans to provide state capital to shore up Europe's major banks. And during its regularly scheduled interest rate meeting on Thursday, the European Central Bank (ECB) committed significant sums of money to come to the aid of financial institutions. ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet warned European governments to ensure that their banks were sufficiently capitalized.

In Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel of the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) has been clear in her support of this position. On Wednesday, together with European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso, she announced her preparedness to support a bank bailout. Following a meeting of the heads of the most important international economics and financial institutions, the chancellor reiterated her position on Thursday, saying that if banks urgently need money, the European states should "not delay" in providing financial aid. That, she said, would be "intelligently invested money."

Crisis Returns to Banks

Behind this week's string of announcements are growing concerns that the European debt crisis is spreading and could soon threaten to engulf major banks, many of which still hold a good deal of Greek government bonds and even more Spanish and Italian securities on their books. Many banks would likely be unable to withstand a national insolvency inside the euro zone. They would be forced to write off billions, and some could face bankruptcy themselves as a result. Trust has diminished to such a degree in recent weeks that interbank lending has dried up, creating a credit crunch not seen in Europe since the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers.

More than anything, though, the threat of a Greek bankruptcy has risen significantly. The Greek economy has collapsed, and the country has once again failed to meet its austerity targets. Patience is now dwindling among the other euro-zone member states that have been stepping up to rescue the country.

Voices calling for an orderly insolvency in Greece are growing. Within the euro zone, this position is most pronounced in Slovakia. But there are also critics within the German government, a group led by Philipp Rösler, the head of the business-friendly Free Democratic Party (FDP), the junior partner in Merkel's coalition. The faction of supporters of insolvency is also growing among economists.

Thomas Straubhaar, director of the influential Hamburg Institute of International Economics, for example, has stated that a system needs to be created that would permit a euro-zone country to go through bankruptcy proceedings. The problem, however, is that so far no one has been able to say how, exactly, an orderly insolvency would proceed.

The consequences could be disastrous for banks. Private financial institutions only recently agreed to write off 21 percent of the value of the Greek government bonds they possess. In the event of an actual insolvency, the losses would be significantly higher -- with many experts predicting banks would have to write off half of their entire Greek bond holdings.

German financial institutions would likely survive a Greek collapse. Data from the recently published stress test indicated that the country's biggest banks -- Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank -- still held Greek securities valuing a total of €1.7 billion and €3 billion, respectively, at the end of 2010. But the banks have already written off a large share of those holdings as losses. Deutsche Bank has stated that the current volume of its Greece portfolio is around €900 million and that all of its Greek securities have already been written down to their current market value.

Saving Banks Cheaper than Rescuing States

"A debt haircut for Greece might be uncomfortable for German banks, but they could cope with it," said Dieter Hein, a banking analyst at independent research institute Fairesearch. The outstanding volume, he said, is no longer high enough to endanger the two banks.

Unfortunately, the problems stretch well beyond two German banks. A Greek insolvency would hit French banks harder and would be catastrophic for financial institutions in Greece. The largest Greek bank, the National Bank of Greece, held close to €19 billion in Greek government bonds on its books at the end of 2010. If forced to write off 50 percent of those securities, the bank's equity capital would vanish in its entirety.

The second problem is potentially even graver. What happens if the pressure created by a Greek insolvency further increases the pressure on other highly indebted nations -- such as Portugal, Spain or Italy -- and drives them to bankruptcy? Under that scenario, there's a good possibility the contagion would become unsustainable for German banks, too. The state would have to infuse them with fresh money in order to rescue the financial institutions from ruin, just as the German government did with Commerzbank following the Lehman Brothers collapse. Only this time around, even more banks would have to be rescued using state funds -- in almost every country in Europe.

European Banks Would Lose €250 Billion in Own Capital

Even so, that might ultimately wind up being cheaper for taxpayers than the ongoing support of indebted states. That, at least, is the belief of German economists Harald Hau and Bernd Lucke, who have calculated a comprehensive scenario for what a wave of bankruptcies in Europe's banks could mean. Under the scenario, Greece and Portugal would undertake a debt haircut of 50 percent, with Italy, Spain and Ireland each eliminating 25 percent of their outstanding debt.

Under the scenario, European banks would lose more than €250 billion in equity capital, which would have to be replaced by government infusions. In Germany, around €20 billion in government money would be needed to shore up the banks. Deutsche Bank would require €3.7 billion and Commerzbank around €6 billion. Together, the euro-zone economies would also have to cover the losses at financial institutions in the countries that went bust -- a figure the economists estimate to be at around €180 billion. As Europe's largest and most solvent country, Germany would have to foot a large portion of that bill.

Sharing the Burden

But the economists still believe it would be cheaper to provide banks with fresh capital than to continue providing ongoing rescue packages for overly indebted countries. In addition, since governments would be given shares of the banks in exchange for the aid, taxpayers would not be left alone to carry the costs of the crisis.

"If the recapitalization is executed at market prices -- in other words, based on the current share price -- then the losses from the expected debt haircut will be carried by the old shareholders," said Hau, who teaches economics and finance at the University of Geneva and at the Swiss Finance Institute. "Initially it would cost taxpayers nothing because they would be given valuable company holdings in exchange."

There would, of course, be one exception: If a bank's losses became so high that they drained their capital entirely, then taxpayers would first have to replenish their equity capital. "Then there would be an actual loss, and there's no way around that," Hau said.

By Hau's calculations, that would apply to only one bank in Germany -- Hypo Real Estate, which he estimates would require around €500 million in capital. Losses of around €30 billion would be expected in the banks in the worst-hit crisis countries.

Hau is convinced that this path is the best one to take. "The bailout package merely protracts the solution to the crisis, but a debt haircut would at least be the beginning of a solution." He also believes his proposal would be fairer. "With a debt haircut, around 80 percent of the costs would be carried by actors in international finance -- from private investors, funds and insurance companies," he said. "Taxpayers would be hit less hard."

As good as that may sound, considerable uncertainty remains over the side effects a debt haircut strategy might have. How long, for example, would banks continue to have to rely on state support? And would governments ever be successful in selling their shares in the banks?

Nevertheless, in the event of state bankruptcies, the euro rescue fund would still be needed because it would take time before crisis countries were able to borrow on their own again from capital markets. Until that time, they would have to be supported by the solvent euro-zone countries. That, it would appear, is unavoidable.

Europe Seems to Agree on Recapitalizing Banks — but How?

by Jack Ewing and Stephen Castle - New York Times

European leaders are finally coming around to the view that banks must be compelled to replenish their capital reserves if the euro area is ever to emerge from the debt crisis. But whether the politicians can make it happen in a convincing manner is another question — especially given that Germany and France are already divided.

Analysts are skeptical that even the richest countries will be able to agree on guidelines for a broad, coordinated effort, one impressive enough to remove all doubts about solvency in the event of a default by Greece or another sovereign debtor.

In the first signs of a split, France wants to draw on the European bailout fund, the European Financial Stability Facility, to rebuild bank capital. German leaders think national governments should take the lead. "Only if a country can’t do it on its own should the E.F.S.F. be used," Chancellor Angela Merkel said on Friday.

But the sums required to armor banks against losses on government bonds — up to 300 billion euros, or about $400 billion, by some estimates — could jeopardize France’s top-notch credit rating. That would be a big political setback for President Nicolas Sarkozy before elections next May.

These kinds of arguments are just what economists fear. A parochial approach will lead countries to try to seek advantage for their own institutions, as has often been the pattern in the past, critics say. In addition, most large European banks have extensive operations and therefore require pan-European oversight, they argue.

"You need to have a European approach, which is tremendously difficult politically," said Nicolas Véron, a senior fellow at Bruegel, a research organization in Brussels. "If it doesn’t happen, I am not very optimistic about the ability of European authorities to keep the crisis under control."

When Fitch Ratings cut Spain’s credit rating Friday by two levels, to AA- from AA+, it cited the "intensification" of the debt crisis along with slower growth and shaky regional finances, Bloomberg News reported. Fitch cited similar reasons for also downgrading Italy one level, to A+, while maintaining Portugal at BBB-, saying it would complete a review of that ranking in the fourth quarter.

Meanwhile, grave problems at the French-Belgian bank Dexia, which is on the verge of its second taxpayer-financed bailout in three years, have dashed any illusions about the health of European banks. It was only in July that Dexia breezed through an official stress test that was supposed to expose vulnerable banks.

It has become obvious that restoring the soundness of European banks is fundamental to resolving the debt crisis and removing a serious threat to the global economy. Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, has been urging a wholesale recapitalization for several months. In the United States, President Obama warned on Thursday that "the problems Europe is having right now could have a very real effect on our economy."

But no one has provided even rough details of how to compel banks to raise money on open markets if they can, and to provide government financing if they can’t. "Our experience is that if no one is talking about the details of something, it is because they do not exist," Carl Weinberg, chief economist of High Frequency Economics, wrote in a note to clients Friday. "Let us just agree that there is no plan."

Mrs. Merkel and Mr. Sarkozy are expected to discuss the issue when they meet in Berlin on Sunday, along with their finance ministers. The European Commission expects to produce its proposal for a coordinated recapitalization within a week.

Even if Dexia proves to be an isolated case, it is clear that investor confidence in the solvency of European banks is at a low ebb. European banks are reluctant to lend to one another, and United States lenders are reluctant to lend to European institutions. Banks have been unable to sell bonds to raise money.

The danger is that European banks will run short of cash to lend to businesses and consumers, amplifying a recession that may already be under way. And in a vicious cycle, the threat of recession is further undermining faith in banks. Investors know that a recession will cause a surge in bad loans, adding to the potential damage if Greece defaults on its bonds.

"The problem is not just bank capital, but first and foremost that of sovereign debt crisis intertwined with slow growth," the Institute of International Finance, a banking industry organization, wrote in its monthly assessment of global capital markets. The report noted that shares of United States banks had begun to suffer because of perceptions that they are exposed to their European peers.

On Thursday, the European Central Bank expanded its aid to banks that were having trouble raising money. It said it would allow banks to borrow as much money as they wanted for about a year at the benchmark interest rate, currently 1.5 percent. And it said it would spend 40 billion euros on a low-risk form of bank debt known as covered bonds.

But, as Jean-Claude Trichet, the departing president, warned, the central bank can provide only temporary aid. The central bank is addressing banks’ liquidity problems — their need for cash day to day. But the E.C.B. cannot fix banks’ solvency problems, the lack of adequate reserves to absorb a big hit to their holdings of government bonds or losses from nonperforming loans.

Before money market funds and other investors will start risking money on European banks again, they need to believe the banks are bulletproof.

Calculations of how much more capital banks need depend on judgments about how bad things may get. Jon Peace, a banking analyst at Nomura, counts at least 25 large publicly traded banks that would need more capital if they fully recognized losses in the value of their holdings of European government bonds. The list includes big names like Commerzbank and Deutsche Bank in Germany, UniCredit in Italy, and Société Générale and BNP Paribas in France.

In addition, there may be dozens, if not hundreds, of other undercapitalized banks that fall below the radar of analysts because they do not have publicly traded shares, like German landesbanks, or because they are too small.

Larger institutions like Deutsche Bank or UniCredit would probably be able to sell new shares. But with bank share prices depressed, it is not an opportune time for even the most credible banks to go to markets.

European leaders plan to debate the issue on Oct. 17 and 18 in Brussels. In addition, governments have asked the European Banking Authority to prepare its own estimate of bank capital needs. Finance ministers have agreed to share information on their own capacity to finance aid to banks when they meet next month.

Given the weight of opinion in the euro zone, the European Commission is likely to side with Mrs. Merkel and argue that the bailout fund should be used for bank recapitalization only as a last resort — unless Mr. Sarkozy can persuade the chancellor otherwise on Sunday.

Germany’s position puts France in a tight spot, though. French banks are some of the most exposed to troubled government debt. Relatively small increases in capital reserves are unlikely to convince the financial markets. But if France were to lose its triple-A credit rating, that would also cause problems for the bailout fund, since France is the second-largest guarantor of the rescue fund, after Germany.

"Merkel has made it clear that she doesn’t see why German taxpayers’ money should be used to rescue French banks which are in competition with her own," said an official in Brussels, who declined to be quoted by name. "France argues that it has made substantial guarantees to the fund and thinks it should be able to use it."

Hedge Funds Are Betting Against Hungary

by Landon Thomas Jr. - New York Times

French and Belgian bank stocks have crashed and the bond yields of Greece, Italy and Portugal may be peaking. Now hedge funds and bond vigilantes have begun to zero in on Hungary as the fashionable European country to bet against.

One of the first countries to get bailed out by the International Monetary Fund in the early days of the financial crisis, Hungary has undergone a severe retrenchment since then with banks, consumers and the government cutting back drastically. Now, after a brief export-driven growth spurt, Hungary, like the rest of Europe, could well be headed for a second recession.

As with Greece, Spain and Italy, the Hungarian government and its large banks have been reliant on foreign investors for their borrowing needs and, as a result, the country’s foreign currency debt burden of 110 percent of gross domestic product is one of the highest in the world.

Crucially, the government sells 50 percent of its debt to foreign investors, and as worries build over the weakening of the forint and drastic antibank measures taken by the government, the bears are betting that Hungary will suffer the same foreign investor strike that led to bailouts for Greece, Ireland and Portugal.

Which may have been why Hungary’s embattled Central Bank governor, Andras Simor — who survived a concerted attempt by the prime minister, Viktor Orban, to fire him last year — made a quick visit to London this week to take the temperature of Hungary’s jittery bond holders.

Mr. Simor is fully aware that in the current risk-averse market, investors who were eager last year to hold higher-yielding Hungarian debt may no longer be willing to do so — especially in light of the controversial actions taken by the government to tax banks and, as he puts it, to "quasi-nationalize" the pension system.

"Any policy maker who says he is not concerned would be crazy," Mr. Simor said on Thursday, referring to the recent flight to safety by emerging markets investors. "This affects countries with large amounts of debt. But I think that if investors look not at the short term but the medium term they will see that this a country that pays a reasonable rate of interest and has a reasonable budget deficit — and I think they will make the right calculation."

Investors may well be looking to the medium term — but not in the way Mr. Simor would want them.

By purchasing credit-default swaps, which have more than doubled in the last three months, and making bets that the country’s banks and bonds have further to fall, some hedge funds are taking the view that money is going to keep fleeing the country, forcing Mr. Simor to keep rates even higher to defend his currency. Since July, the forint has weakened in value against the euro to 296, from 264 — perhaps the clearest sign that investors are losing confidence in Hungary.

Hungary has also suffered from the strong Swiss franc as loans in this currency, particularly in the mortgage market, are 20 percent of G.D.P.

While Mr. Simor was critical of some of the government’s more unconventional measures, he argued that the economy was in much better shape than it was two years ago, with a target budget deficit of just 2 percent of G.D.P. for 2012.

Because Hungary is not a member of the euro zone, a crisis would not have the systemic effect of a Greek collapse. But with the resources of the International Monetary Fund now focused on greater Europe, a Hungarian rescue operation would come at a bad time — especially as relations between the fund and the current government are strained. It is also true that large banks in Italy and Austria have significant operations in Hungary

Japan's Central Bank Sounds Warning on Global Economy

by Hiroko Tabuchi - New York Times

The Japanese central bank sounded the alarm over the risks facing the world economy, even as it left its monetary policy unchanged Friday, underscoring the gravity of a global economic slowdown over which policy makers may have little control.

Also Friday, the Japanese cabinet outlined a supplemental budget of ¥12 trillion, or $155 billion, for the reconstruction of areas affected by the natural and nuclear disasters this year, the third such budget, and approved a plan to raise taxes temporarily to fund the effort.

The latest emergency budget follows about ¥6 trillion already earmarked in two supplemental budgets this year. It includes money to help relocate survivors and create a fund to revitalize the economy of Fukushima Prefecture, which has been hit hard by the nuclear crisis.

The government will raise up to ¥11.2 trillion from temporary taxes to help cover costs of rebuilding, according to the provisional tax plan. Officials have said they would also cut unnecessary government expenditures and sell state-owned assets, possibly including the government’s entire stake in Japan Tobacco.

The government has yet to work out the details of any extra spending, as well as tax increases, and must also win the approval of a divided Parliament. It aims to submit the budget to Parliament later this month, according to Kyodo News. "The uncertain outlook for the global economy and instability in financial markets are underscoring the downside risks for Japan’s economy," said Masaaki Shirakawa, the Bank of Japan governor.

The world’s advanced economies, in particular, are on the brink of a major slowdown, threatening the Japanese economy, he warned. The European debt crisis has started to cause real damage to the economies in Europe and beyond, he said.

"European financial markets remain tense, as there have been moves in money markets similar to those seen during the Lehman crisis," he said, referring to the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. "What’s different is that the credibility of government debt has become the target of market worries, and this has resulted in bigger impact."

The global economic problems have affected the Japanese economy just as it has shown signs of recovery following the hugely disruptive earthquake and tsunami in March, and the subsequent nuclear crisis. Economists say they expect figures to show that Japan emerged from recession in the third quarter, as companies restored supply chains disrupted by the disasters.

The International Monetary Fund forecasts that the Japanese economy will grow 2.3 percent in 2012, the fastest among advanced economies, thanks to Japan’s large fiscal outlays for reconstruction, in contrast with fiscal austerity measures imposed elsewhere in the world.

But prospects for a strong rebound of the country’s exports — on which Japan ultimately depends for economic growth — are looking increasingly frail. Particularly worrying has been the strong yen, which has surged as investors look for a haven in which to park their assets. The strength of the yen has hurt Japan by making its exports less competitive and eroding exporters’ overseas profits.

Still, the central bank, with interest rates already near zero and a reluctance to flood the economy with more money, has little left in its policy arsenal to bolster the Japanese economy. Its kept its key interest rate untouched at a range of zero to 0.1 percent and maintained the size of its asset-buying program.

It extended by only six months a ¥1 trillion emergency loan program for regions hit by the March disasters. Half that amount remains untapped amid a still-tepid economic recovery in disaster-affected areas.

The bank’s decision came after the European Central Bank also kept interest rates steady, though it threw a lifeline to struggling banks to ward off a credit crunch. Also Thursday, the Bank of England announced a second round of monetary easing.

Clamping Down on High-Speed Stock Trades

by Graham Bowley - New York Times

Regulators in the United States and overseas are cracking down on computerized high-speed trading that crowds today’s stock exchanges, worried that as it spreads around the globe it is making market swings worse.

The cost of these high-frequency traders, critics say, is the confidence of ordinary investors in the markets, and ultimately their belief in the fairness of the financial system. "There is something unholy about them," said Guy P. Wyser-Pratte, a prominent longtime Wall Street trader and investor. "That is what caused this tremendous volatility. They make a fortune whereas the public gets so whipsawed by this trading."

Regulators are playing catch-up. In the United States and Europe, they have recently fined traders for using computers to gain advantage over slower investors by illegally manipulating prices, and they suspect other market abuse could be going on. Regulators are also weighing new rules for high-speed trading, with an international regulatory body to make recommendations in coming weeks.

In addition, officials in Europe, Canada and the United States are considering imposing fees aimed at limiting trading volume or paying for the cost of greater oversight.

Perhaps regulators’ biggest worry is over the unknown dynamics of the computerized stock market world that the firms are part of — and the risk that at any moment it could spin out of control. Some regulators fear that the sudden market dive on May 6, 2010, when prices dropped by 700 points in minutes and recovered just as abruptly, was a warning of the potential problems to come. Just last week, the broader market fell throughout Tuesday’s session before shooting up 4 percent in the last hour, raising questions on what was really behind it.

"The flash crash was a wake-up call for the market," said Andrew Haldane, executive director of the Bank of England responsible for financial stability. "There are many questions begging."

The industry and others say that the vast majority of trading is legitimate and that its presence means many extra buyers and sellers in the markets, drastically reducing trading costs for ordinary investors.

James Overdahl, an adviser to the firms’ trade group, said that they favor policing the market to stamp out manipulation and that they support efforts to improve market stability. The traders, he said, "are as much interested in improving the quality of markets as anyone else." Some academic studies show that high-frequency trading tends to reduce price volatility on normal trading days.

And while a recent analysis by The New York Times of price changes in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index over the past five decades showed that big price swings are more common than they used to be, analysts ascribe this to a variety of causes — including high-speed electronic trading but also high anxiety about the European crisis and the United States economy.