How to become a man in Omar, West Virginia

Ilargi: Today was not the easiest one of all, connection wise. I did manage to get me, late aft, to a bar that has internet access, while our home access has been dead for most of the day, but the bar is sort of loud and there was a pool cue in my neck just now. And I can't write in that sort of setting. So I think that until tomorrow, all I can do is, I will leave you to answer a question: Who wants to get rid of Tim Geithner? Someone does. The NYT doesn't run a front-page article on Tim’s banking connections for nothing. A hint (but no more than that): the article, as well as the graphic that comes with it -see the bottom of my first post today- talks extensively about Robert Rubin’s decade at Citigroup, and his 3+ years as Treasury Secretary. But not one single word about his 26 years at Goldman Sachs. Still, Rubin is what links Goldman to Citi to the White House. Anyway, I’ll see you tomorrow.

As Crisis Loomed, Geithner Pressed But Fell Short

In September 2005, Timothy Geithner made one of his most visible moves as a supervisor of the U.S. banking system. He summoned the nation's top financial firms and their regulators to streamline an antiquated system that threatened Wall Street's boom. Billions of dollars worth of financial instruments known as credit derivatives were being traded daily, as banks and investors worldwide tried to protect against losses on increasingly complex and risky financial bets. But the buying and selling of these exotic instruments was stuck in a pencil-and-paper era. Geithner, then head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, pressed 14 major financial firms to build an electronic network that would cut backlogs and make the market easier to monitor.

Geithner's summit, held at the New York Fed's fortress-like headquarters near Wall Street, was a success. By fall 2006, the new system had all but eliminated the logjam, helping derivatives trade more efficiently. One financial industry newsletter honored Geithner as part of a "Dream Team" for his leadership of the effort. Yet as Geithner and the New York Fed worked to solve narrow mechanical issues in the derivatives market, they missed clear signs of a catastrophe in the making. When the housing market collapsed, derivatives stoked the fires that ignited inside some of the biggest banking companies. The firms' failure to assess an array of risks they were taking has emerged as a key element in the multi-trillion dollar meltdown of the global financial system.

Although Geithner repeatedly raised concerns about the failure of banks to understand their risks, including those taken through derivatives, he and the Federal Reserve system did not act with enough force to blunt the troubles that ensued. That was largely because he and other regulators relied too much on assurances from senior banking executives that their firms were safe and sound, according to interviews and a review of documents by The Washington Post and the nonprofit journalism organization ProPublica. A confidential review ordered by Geithner in 2006 found that banking companies could not properly assess their exposure to a severe economic downturn and were relying on the "intuition" of banking executives rather than hard quantitative analysis, according to interviews with Fed officials and a little-noticed audit by the Government Accountability Office (PDF). The Fed did not use key enforcement tools until later, after the credit crisis erupted, according to its records and interviews.

Geithner defended his tenure as New York Fed president in an interview last week. He said he had been "deeply concerned about risk in the system" and worked assiduously behind the scenes to cajole banking institutions to do more to identify weaknesses and protect the financial system. But he also took some responsibility for falling short. "These efforts to improve risk management did change behavior, but they did not achieve enough traction," Geithner said. "We're having a major financial crisis in part because of failures of supervision." Even as critics have questioned how he used existing power before the crisis, Geithner, as Treasury secretary, now leads the push for the biggest expansion of financial regulation since the Great Depression. His sweeping plan to overhaul the U.S. financial system would empower regulators to broadly analyze risk and would grant more authority to the Fed and its 12 reserve banks.

Geithner says he is applying lessons from his five years at the most important of the Fed's reserve banks. This week, he assumed an even more prominent platform, joining President Obama in London at a meeting with the Group of 20 industrialized nations to discuss global financial regulatory reform. Looking back at his time at the New York Fed, Geithner said: "I wish I had worked to change the framework, rather than to work within that framework." Geithner, 47, adopted the diplomatic approach to supervision that had long held sway at the New York Fed, a hybrid institution that is owned by the banks but implements monetary policy for the Federal Reserve. Like the other regional Feds, it also shares supervisory authority with the central bank. Six of its nine board members are chosen by the commercial banking companies it supervises. The board plays a role in the selection of the New York Fed president.

Although the Federal Reserve system, and the New York Fed in particular, was responsible for watching for systemwide risks, Geithner said that the Fed was limited by a lack of explicit authority over financial institutions outside the banking system. One key example was insurance giant American International Group, whose derivative transactions helped fuel the financial collapse last fall. As part of Geithner's confirmation process for Treasury secretary, Democratic and Republican senators questioned why he and the New York Fed did not take a tougher approach with the troubled institutions it did regulate, such as Citigroup, then the largest under its supervision and the one hardest hit by the financial collapse. Geithner, who maintained ties to senior bank executives and others in the financial world, had a particularly close relationship with former Treasury secretary Robert E. Rubin, a mentor then serving as a senior executive at Citigroup. In 2007 and 2008, Geithner held discussions with Citigroup officials dozens of times, more than with any other firm, according to interviews and documents, including Geithner's daily calendar.

Some lawmakers in both parties are asking whether bank regulators in general were too close to the institutions they oversaw. Geithner says meetings with executives from Citigroup and other firms were a routine part of his job. He said checks and balances built into the Federal Reserve system preserve the independence of Fed officials. Gerald Corrigan, a managing director of Goldman Sachs who once held Geithner's job, said every New York Fed president faces the same challenge - supervising the very banks they rely on for information. "The effectiveness of the New York Fed clearly does depend on frequent and open dialogue between the Fed and the leaders of the major financial institutions," Corrigan said. "Striking that balance is never easy," he said. "On the whole, Tim did a reasonably good job."

Geithner is trim, boyish-looking and thoughtful, parsing his ideas with academic care. Unlike some of his predecessors at the Fed, he did not bring a banker's résumé to the job. A protege of former secretary of state Henry Kissinger at his consulting firm, he joined the Treasury and rose through the ranks with support from two Clinton-era secretaries, Rubin and Lawrence H. Summers. Geithner eventually served as undersecretary for international affairs, where he oversaw the department's response to the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. When he arrived at the New York Fed in fall 2003, the derivatives market had begun to soar. One type of derivative known as a credit-default swap is a contract that operates much like insurance for complex financial transactions. They greatly enhanced Wall Street's ability to package mortgages into exotic securities that could be resold to investors. That, in turn, fueled the housing bubble by expanding the supply of money for home loans.

But by 2005 the paperwork for derivatives contracts was swamping the back offices of big financial firms. Stacks of documents sat unattended. The archaic system was not only bad for business, it impeded the market from properly pricing deals. "They didn't know what their positions were," Geithner said in the interview. "This was a huge collective action problem." Under Geithner's direction, the banks formally agreed after months of meetings in early 2006 to fix the problem together. At the time, many bankers and regulators were convinced that credit derivatives had in just a few years strengthened the world's financial system. Alan Greenspan, then chairman of the Federal Reserve, set the rhetorical tone for the Fed's advocacy of such deals. "The development of credit derivatives," Greenspan said in a May 2005 speech, "has contributed to the stability of the banking system by allowing banks, especially the largest, systemically important banks, to measure and manage their credit risks more effectively."

Geithner often cited the merits of credit derivatives as well, saying in a May 2006 speech at New York University that they "probably improve the overall efficiency and resiliency of financial markets." By then, some financial institutions already were worried about the subprime mortgages underlying exotic securities. AIG's Financial Products unit, one of the largest issuers of credit-default swaps, stopped offering that insurance. Even so, few understood the magnitude of the looming disaster. "What nobody knew was that credit derivatives had moved from a risk diversification and risk management vehicle to the world's biggest gambling casino," said H. Rodgin Cohen, a New York attorney for large financial companies such as J.P. Morgan Chase and Wachovia.

Although he later said he didn't see the larger danger, Geithner at the time expressed concern about whether the large banks he supervised fully understood their vulnerabilities. In the NYU speech, he said they would need to take a "cold, hard look" at the interlocking effects of such deals across the financial system. That same year he initiated a Fed-wide review of how well the financial giants were able to measure their ability to survive the stresses of a market downturn. William Rutledge, the New York Fed's executive vice president for bank supervision, said the reviews turned up several weaknesses. They found that banking companies were pretty good at measuring the risks to specific parts of their businesses but had little understanding of the dangers to the institution as a whole. The firms also failed to account for the kind of worst-case scenarios that would later cripple several banking giants.

The New York Fed followed up the study of the stress tests by holding private discussions with bank managers. The Fed officials sought among other things to "encourage" firms to improve their "credit risk-management practices" and to engage in "careful reflection" of their assessment of the global economy's health, Rutledge said in a written response to questions. Cohen, the banking lawyer, said that Geithner privately "was pushing the system to reform." But because of limited resources, Geithner was reliant on the big banks for information about their activities, Cohen said. GAO auditors who recently reviewed the confidential Fed study said the banks pushed back against the idea of expanding their stress tests. Executives "questioned the need for additional stress testing, particularly for worst-case scenarios that they thought were implausible," Orice Williams, the director of financial markets at the GAO, told the Senate subcommittee on Securities, Insurance, and Investments last month.

Williams said that regulators "did not take forceful action" to correct the risk-management deficiencies "until the crisis occurred." Records and interviews show that Geithner and his colleagues did not employ some of the harsher tools at their disposal to bring the banks into line. From 2006 through the start of the credit crisis in the summer of 2007, they brought no formal enforcement actions against any large institution for substandard risk-management practices. The Fed also did not use its confidential process during that period to downgrade any large bank company's risk rating, according to two people familiar with the process, a step that could have triggered costly consequences for the firms. A spokesman for the New York Fed said it does not comment on private supervisory actions.

The New York Fed led a broader review of the large banks' risk management in early 2007, just months before the credit crisis began. Unlike the 2006 study, the review, titled "Large Financial Institutions' Perspectives on Risk," gave an upbeat assessment of their ability to handle potential vulnerabilities. Relying on bank assurances that the quality of their loans and investments remained "strong," the Fed concluded that there were "no substantial issues of supervisory concern." When Congress learned of the Fed reports during last month's hearing, some lawmakers questioned the close relationships between the regulators and banks. They suggested that the Fed's practice of keeping its findings confidential may have contributed to the crisis. "There might have been earlier, prompter and more effective action to deal with some of these issues that are bedeviling us at the moment," said Sen. Jack Reed (D-R.I.). "In many respects you are captives of the information of the organization you're regulating."

The recent criticism of the New York Fed raises questions about its dual mandate to be both a supervisor and the government's eyes and ears on the nation's financial markets. Like his predecessors, Geithner relied upon extensive contact with senior banking officials to collect information and influence their practices. "He had a remarkable ability to gain information without giving up information or without giving up his independence," said Cohen, the banking lawyer. Cohen, who was in the running earlier this year to be Geithner's deputy at the Treasury, is among hundreds of people listed in Geithner's 2007 and 2008 appointment calendars, which were made available by the New York Fed. Geithner's outside contacts include senior banking managers, Treasury officials, regulators from other nations and journalists. The appointments range from breakfasts and lunches with bankers to tennis with Alan Greenspan and "Dinner w/ Dr. and Mrs. Kissinger, et. al."

No institution shows up as frequently as Citigroup, the biggest bank company under the New York Fed's supervision. Among the numerous senior Citigroup officials recorded were Geithner's mentor Rubin, chief executive Charles Prince and his successor, Vikram Pandit. Citigroup officials declined to comment for this report. The calendar entries offer few details on the meetings, but the New York Fed had no shortage of topics to discuss with the bank holding company about its far-flung operations and its increasing exposure to subprime mortgages. In 2005, as regulators abroad investigated Citigroup for imprudent trading practices, the Fed banned it from making new acquisitions. The ban was lifted in April 2006 after Citigroup assured the New York Fed it had tightened its compliance. At the end of that year, without public explanation, the Fed also terminated a three-year-old public-enforcement agreement that required Citigroup to beef up its risk management and file regular reports with the Fed.

At the time, Citigroup was taking on more risk. It was reporting record profits while also doubling its exposure to the subprime market. In 2006 Citigroup originated nearly twice as many subprime mortgages as the year before. It also issued twice as many exotic securities known as collateralized debt obligations - including many comprised of subprime loans. By fall 2007, Citigroup began to recognize huge losses from these and other bets. At the urging of Geithner and the Fed, Citigroup began raising more capital to fill the growing holes in its balance sheets and reassure the markets of its solvency. Citigroup's level of capital exceeded regulatory minimums. But the Fed did not require the banking company to raise the level to that of its peers. At the end of 2007, the capital level also fell below Citigroup's internal target.

A few months later, banking analysts raised questions about Citigroup's capital reserves. During the company's annual conference in early May, Pandit was asked whether there was tension between the banks, the auditors and the regulators over that issue. Pandit said that Citigroup was in "perfect agreement" with regulators and auditors. When an analyst expressed skepticism, another Citigroup executive backed up Pandit, saying there was "kind of an unusual symmetry." In June 2008, Geithner told the Economic Club of New York that the guidelines for bank capital needed to be reworked - but not yet. "After we get through this crisis, and the process of stabilization and financial repair is complete, we will put in place more exacting expectations on capital, liquidity and risk management for the largest institutions," he said. By the fall, the only place beleaguered Citigroup could find capital was the U.S. Treasury. The government initially injected $25 billion to keep the company afloat. That wasn't enough. A few weeks later it came up with another $20 billion in cash and guarantees that would cover nearly $250 billion in losses on its toxic assets. No banking firm has received a larger federal bailout.

Geithner was working on the second Citigroup rescue, when, on Nov. 21, word leaked that President-elect Barack Obama wanted to name him Treasury Secretary. Geithner had two meetings that day with top Citigroup executives, according to his calendar. Then he quickly stepped aside from further involvement in the rescue of financial institutions. Before his confirmation hearing Geithner paid courtesy calls in the Senate. He mostly got a warm reception. When he went to see Sen. Ron Wyden, the Oregon Democrat quizzed him about his supervision of Citigroup. "I quoted to him from the U.S. code," Wyden said, "about the clear responsibilities of the New York Fed." Wyden wanted to know why the "alarm bells" about Citigroup hadn't prompted the Fed to "enforce existing laws." A few days later Geithner appeared before the Senate Finance Committee. Wyden once again asked why Geithner missed the boat with Citigroup.

Geithner acknowledged that "supervision could have been more effective." Before he could continue, Wyden pressed him: "Should your supervision have been more effective?" "Absolutely," Geithner said. As the Fed prepares to take on even more responsibility in a new financial regulatory architecture, it also is engaged in what Federal Reserve vice chairman Donald Kohn describes as a "comprehensive 'lessons learned' review" of the credit crisis. In an interview, Kohn, who is leading the review, declined to discuss the findings so far. Roger T. Cole, the central bank's head of banking supervision, told Congress two weeks ago that one lesson among many is that regulators must no longer be lulled by good times or put off by industry arguments. "When bankers are particularly confident, when the industry and others are especially vocal about the costs of regulatory burden and international competitiveness, and when supervisors cannot yet cite recognized losses or write-downs," Cole said, "we must have even firmer resolve to hold firms accountable for prudent risk management."

FDIC's Bair: Too Big To Fail Should Be Tossed In Dustbin

Sheila Bair, the chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., pushed aside one of the most fabled issues in the U.S. banking system: Too big too fail. The two decade old concept allows the nation's largest banks to keep operating even under condition that would put smaller banks out of business, because the big banks have a bigger role in keeping the banking system operating. But, as a matter of fairness, small banks and big banks should not be treated differently, Bair said.But during a luncheon speech at the Economic Club of New York, Bair said, "Too big to fail should be tossed in to the dustbin." Instead, regulators need a new way to unwind troubled large banks in a way that would not be "a get out of jail free card."

That leaves a question: Which regulator should be in charge of resolving large financial institutions? To Bair, the answer is that her own institution, rather than a new regulatory authority, should be given that authority. So far, the FDIC only regulates banks and bank subsidiaries, not bank holding companies. The FDIC's tools fall short when it comes to large institutions, she said. She dismissed suggestions that the FDIC has no experience in resolving big troubled banks, but Bair noted that neither has any other regulator. "We are good at" closing banks, she said. Closing a bank "is never pleasant," but "we cannot solve the problem" with the too big to fail concept in place, she said. Bair also said that other big banks should be partially financially responsible for the failure of big, systematically important banks. "Who should pay?" if a big banks is in trouble, she asked. "Not the tax payer, nor the FDIC fund." She suggested that perhaps a new assessment of large firms should be imposed.

Meanwhile, Bair said "we have moved beyond" the liquidity crisis that hit the banking system in mid-2007 and hampered banks all last year. "As I see it, we are now in the clean-up phase. We have to repair...and get out," she said. Bair reiterated her support for the bad bank structure that would relieve banks from their troubled assets, and said that shareholders should bear some of the financial burden to set that bad bank up. She also said that PPIP is one tool to solve the crisis, and reiterated that giving banks a stake in the loans they sell through the program might help getting it going. But she said when banks manage to get over their bad assets, they "are well positioned" for the longer term. Bair said banks shouldn't be allowed to pay back money from the Troubled Asset Relief Program without consulting with their supervisors.

Ilargi: Has Krugman finally woken up, half a year after his Fake Nobel and the sauna-pool of Aquavit that came with it? I’m not holding ny breath.

Money for Nothing

On July 15, 2007, The New York Times published an article with the headline “The Richest of the Rich, Proud of a New Gilded Age.” The most prominently featured of the “new titans” was Sanford Weill, the former chairman of Citigroup, who insisted that he and his peers in the financial sector had earned their immense wealth through their contributions to society. Soon after that article was printed, the financial edifice Mr. Weill took credit for helping to build collapsed, inflicting immense collateral damage in the process. Even if we manage to avoid a repeat of the Great Depression, the world economy will take years to recover from this crisis. All of which explains why we should be disturbed by an article in Sunday’s Times reporting that pay at investment banks, after dipping last year, is soaring again — right back up to 2007 levels.

Why is this disturbing? Let me count the ways. First, there’s no longer any reason to believe that the wizards of Wall Street actually contribute anything positive to society, let alone enough to justify those humongous paychecks. Remember that the gilded Wall Street of 2007 was a fairly new phenomenon. From the 1930s until around 1980 banking was a staid, rather boring business that paid no better, on average, than other industries, yet kept the economy’s wheels turning. So why did some bankers suddenly begin making vast fortunes? It was, we were told, a reward for their creativity — for financial innovation. At this point, however, it’s hard to think of any major recent financial innovations that actually aided society, as opposed to being new, improved ways to blow bubbles, evade regulations and implement de facto Ponzi schemes.

Consider a recent speech by Ben Bernanke, the Federal Reserve chairman, in which he tried to defend financial innovation. His examples of “good” financial innovations were (1) credit cards — not exactly a new idea; (2) overdraft protection; and (3) subprime mortgages. (I am not making this up.) These were the things for which bankers got paid the big bucks? Still, you might argue that we have a free-market economy, and it’s up to the private sector to decide how much its employees are worth. But this brings me to my second point: Wall Street is no longer, in any real sense, part of the private sector. It’s a ward of the state, every bit as dependent on government aid as recipients of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, a k a “welfare.”

I’m not just talking about the $600 billion or so already committed under the TARP. There are also the huge credit lines extended by the Federal Reserve; large-scale lending by Federal Home Loan Banks; the taxpayer-financed payoffs of A.I.G. contracts; the vast expansion of F.D.I.C. guarantees; and, more broadly, the implicit backing provided to every financial firm considered too big, or too strategic, to fail. One can argue that it’s necessary to rescue Wall Street to protect the economy as a whole — and in fact I agree. But given all that taxpayer money on the line, financial firms should be acting like public utilities, not returning to the practices and paychecks of 2007. Furthermore, paying vast sums to wheeler-dealers isn’t just outrageous; it’s dangerous. Why, after all, did bankers take such huge risks? Because success — or even the temporary appearance of success — offered such gigantic rewards: even executives who blew up their companies could and did walk away with hundreds of millions. Now we’re seeing similar rewards offered to people who can play their risky games with federal backing.

So what’s going on here? Why are paychecks heading for the stratosphere again? Claims that firms have to pay these salaries to retain their best people aren’t plausible: with employment in the financial sector plunging, where are those people going to go? No, the real reason financial firms are paying big again is simply because they can. They’re making money again (although not as much as they claim), and why not? After all, they can borrow cheaply, thanks to all those federal guarantees, and lend at much higher rates. So it’s eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow you may be regulated. Or maybe not. There’s a palpable sense in the financial press that the storm has passed: stocks are up, the economy’s nose-dive may be leveling off, and the Obama administration will probably let the bankers off with nothing more than a few stern speeches. Rightly or wrongly, the bankers seem to believe that a return to business as usual is just around the corner. We can only hope that our leaders prove them wrong, and carry through with real reform. In 2008, overpaid bankers taking big risks with other people’s money brought the world economy to its knees. The last thing we need is to give them a chance to do it all over again.

Home Vacancies Rise in U.S. to Record Amid Recession

A record 19.1 million homes stood unoccupied in the first quarter and the U.S. homeownership rate fell as the recession sapped demand for real estate. The number of vacant homes, including foreclosures, properties for sale and vacation properties, jumped from 18.6 million a year earlier, the U.S. Census Bureau said in a report today. Households that own their own residence declined for the third straight quarter to 67.3 percent. The U.S. financial crisis and falling home prices have shattered the confidence of homebuyers. The percentage of people who said they plan to buy a home in the next six months dropped to a 26-year low in March, according to the Conference Board in New York. Job losses will continue to erode real estate demand, according to an April 23 report by Mark Fleming, chief economist for First American CoreLogic Inc. in Santa Ana, California.

“We expect home prices to continue to decline into 2010 as economic conditions and excess housing inventories dampen prices,” Fleming said in the report. “Decreases are now being driven by rising unemployment and a high volume of distressed home sales.”The percentage of all U.S. homes empty and for sale, known as the vacancy rate, fell to 2.7 percent in the first quarter. It hit an all-time high of 2.9 percent in the first and fourth quarters of 2008, the Census Bureau said. The vacancy rate fell as the number of homes on the market declined because they were sold or because their owners gave up trying to market them. The inventory of homes on the market averaged 3.7 million in each of 2009’s first three months, according to data from the National Association of Realtors. Last year, the monthly average was 4.2 million.

There were 130.4 million homes in the U.S. in the first quarter, the Census Bureau said. In addition to the 2.1 million empty properties for sale, the report counted 4.2 million vacant homes for rent and 4.9 million seasonal properties that are only used for part of the year. Foreclosures are included in a part of the Census Bureau that also includes vacation homes intended for year-round use and homes that are unoccupied because they are under renovation. There were 7.9 million such properties empty in the first quarter, up from 7.5 million a year earlier, the report said. Foreclosures could also be counted as vacant homes for sale or rent, or as owner-occupied properties if lenders have not yet evicted previous owners, the agency said. The economy has lost about 5.1 million jobs since the recession began in December 2007, the biggest drop of the post- war era. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg in early April said unemployment probably will rise to 9.5 percent by the end of the year, up from March’s 25-year high of 8.5 percent.

The share of mortgages in foreclosure rose to an all-time high of 3.3 percent in the fourth quarter, the Mortgage Bankers Association said in a March 5 report. Delinquencies, or the percentage of home loans that have payments 30 days or more overdue, increased to 7.88 percent, the highest in records dating to 1972, the Washington-based trade group said. Banks held $11.5 billion of foreclosed properties in the fourth quarter, up from $6.5 billion in the year-earlier period, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. in Washington.

Stress Tests May Force Banks to Convert TARP Stock to Common Shares

U.S. banks that received results of their federal stress tests last week were given three options if they need additional capital to withstand the recession. The reality is they may only have one. Getting federal aid or selling shares -- two of the choices offered to the 19 lenders being tested -- aren’t practical politically or financially, according to analysts, including Jeff Davis, the research director at Howe Barnes Hoefer & Arnett Inc. in Chicago. Lawmakers have opposed adding more to the $700 billion that the government already committed and investors have balked at buying shares of financial firms after a two-year drop. That leaves the third option presented by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner: changing the preferred stock held by the U.S. Troubled Asset Relief Program into common shares. Doing so would prop up capital under accounting rules and dilute the value of shareholdings for current investors.

SunTrust Banks Inc., KeyCorp and Regions Financial Corp., pegged by Morgan Stanley last week as the “most likely” to need capital, dropped more than 70 percent in New York Stock Exchange composite trading during the past year. SunTrust dropped 31 cents, or 2 percent, to $15.65 at 10:40 a.m. New York Stock Exchange composite trading and KeyCorp slid 6 percent to $6.59. Regions declined 3.6 percent to $5.36. “The best most can hope for is to stay as they are and not be forced to draw down still more TARP capital or convert what they’ve got into common stock,” said Karen Petrou, managing partner of Washington-based research firm Federal Financial Analytics Inc. Bank executives received preliminary results from the Federal Reserve reviews on April 24. The stress tests aim to identify potential losses and how much capital banks will require should the economic slump worsen in the next two years.

Geithner can’t ask for more money from Congress, which may force banks that need funds to convert the government’s preferred holdings into common equity, said Davis, whose firm tracks the financial-services industry. Lawmakers have said they oppose allocating more money for TARP because of the high costs, lack of disclosures on how the money is being used and concerns about bonuses paid to executives of money-losing companies, including American International Group Inc. and Merrill Lynch & Co. Lenders that need funds will be able to obtain money through the government or private sources, White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel said in an April 24 interview on Bloomberg Television’s “Political Capital With Al Hunt.” Emanuel said that the Treasury has enough left from the original sum, and Geithner said April 21 that $109.6 billion remains in TARP, or $134.6 billion including expected repayments in the coming year.

The Federal Reserve, which oversaw the stress tests, wants common equity to be the “dominant” element in a bank’s capital. The Fed didn’t specify a particular target for a bank’s ratio of tangible common equity, or TCE, to tangible assets. TCE is a measure of a bank’s financial health that excludes intangibles such as brand names that can’t actually be used as payments. Investors and analysts have focused on the ratio as a more accurate benchmark of a bank’s ability to absorb losses. The industry was examined as bad assets soared 169 percent from a year earlier at 13 of the largest U.S. banks, according to first-quarter data compiled by Bloomberg. U.S. unemployment rose to 8.5 percent in March, the highest since 1983, as the economy shed 663,000 jobs. The stress test examined a bank’s capital adequacy assuming unemployment rises as high as 10.3 percent in 2010 and home prices drop as much as 7 percent.

The Fed study focused on loss projections for consumer, commercial, industrial and commercial real estate loans, and on the securities that banks hold. Analysts at New York-based KBW Inc., led by Frederick Cannon, said banks may require another $1 trillion of capital to cover losses as the economy deteriorates. Banks were given preliminary results last week, with a final report to be published May 4. The 19 firms include Citigroup Inc., Bank of America Corp.,Goldman Sachs Group Inc., GMAC LLC,MetLife Inc. and regional lenders, including Fifth Third Bancorp and Regions.

Representatives of the banks either couldn’t be reached this weekend or declined to comment. Financial stocks rose April 24 even as the Fed stopped short of indicating how much new money regulators will demand that banks raise. The report said “most” companies have capital “well in excess” of regulatory requirements; it didn’t specify how the stress tests may affect those levels. Senior executives and directors may find their jobs are at stake, depending on their cash needs. Geithner said April 5 that regulators may change management at any company that needs “exceptional assistance.”

Bank of America Chief Executive Officer Kenneth D. Lewis said March 12 that his company won’t need more taxpayer help after two sales of preferred stock to the U.S. totaling $45 billion and $118 billion in federal asset guarantees to help absorb losses from the Jan. 1 acquisition of Merrill Lynch. Lewis, 62, is under fire for not telling shareholders that Merrill Lynch’s fourth-quarter losses were spiraling past $15 billion before they voted to approve the takeover. The losses led to the second sale of preferred stock to the U.S. in January, adding to the amount of potential dilution for shareholders. Investors groups are calling for Lewis’s ouster at this week’s annual meeting, or for his role as chairman and CEO to be split. Directors are concerned the vote may be close, people familiar with the matter have said. “People look at the stress test as a way of identifying who’s going to get more government money and more government control,” said Jeff Berman, a New York-based partner at law firm Clifford Chance LLP.

A Good Share of the Blame

by Michael Panzner

OK, I admit it: I missed seeing it the first time around. Regardless, as I was doing my usual search-and-sift for information and insights on the current crisis, I came across an interesting document, published in March by the Consumer Education Foundation, a California-based non-profit, non-partisan consumer research, education and advocacy organization. Entitled "Sold Out: How Wall Street and Washington Betrayed America," the 231-page report makes the case that the current mess is the direct result of bad behavior on Wall Street and the corrupt connection between the powerful moneyed interests and those who make policy in Washington (and elsewhere). Although I think there is a much more to it than that -- as I've noted in Financial Armageddon, many people played a role in getting us to this point, including ordinary Americans -- and that there are plenty of honest, hard-working people on Wall Street (and maybe even in our nation's capital), the argument certainly has merit. Below is the report's "Executive Summary":

Blame Wall Street for the current financial crisis. Investment banks, hedge funds and commercial banks made reckless bets using borrowed money. They created and trafficked in exotic investment vehicles that even top Wall Street executives—not to mention firm directors—did not understand. They hid risky investments in off balance- sheet vehicles or capitalized on their legal status to cloak investments altogether. They engaged in unconscionable predatory lending that offered huge profits for a time, but led to dire consequences when the loans proved unpayable. And they created, maintained and justified a housing bubble, the bursting of which has thrown the United States and the world into a deep recession, resulted in a foreclosure epidemic ripping apart communities across the country. But while Wall Street is culpable for the financial crisis and global recession, others do share responsibility. For the last three decades, financial regulators, Congress and the executive branch have steadily eroded the regulatory system that restrained the financial sector from acting on its own worst tendencies.

The post-Depression regulatory system aimed to force disclosure of publicly relevant financial information; established limits on the use of leverage; drew bright lines between different kinds of financial activity and protected regulated commercial banking from investment bank-style risk taking; enforced meaningful limits on economic concentration, especially in the banking sector; provided meaningful consumer protections (including restrictions on usurious interest rates); and contained the financial sector so that it remained subordinate to the real economy. This hodge-podge regulatory system was, of course, highly imperfect, including because it too often failed to deliver on its promises. But it was not its imperfections that led to the erosion and collapse of that regulatory system. It was a concerted effort by Wall Street, steadily gaining momentum until it reached fever pitch in the late 1990s and continued right through the first half of 2008.

Even now, Wall Street continues to defend many of its worst practices. Though it bows to the political reality that new regulation is coming, it aims to reduce the scope and importance of that regulation and, if possible, use the guise of regulation to further remove public controls over its operations. This report has one overriding message: financial deregulation led directly to the financial meltdown. It also has two other, top-tier messages. First, the details matter. The report documents a dozen specific deregulatory steps (including failures to regulate and failures to enforce existing regulations) that enabled Wall Street to crash the financial system. Second, Wall Street didn’t obtain these regulatory abeyances based on the force of its arguments. At every step, critics warned of the dangers of further deregulation. Their evidence-based claims could not offset the political and economic muscle of Wall Street. The financial sector showered campaign contributions on politicians from both parties, invested heavily in a legion of lobbyists, paid academics and think tanks to justify their preferred policy positions, and cultivated a pliant media—especially a cheerleading business media complex.

Part I of this report presents 12 Deregulatory Steps to Financial Meltdown. For each deregulatory move, we aim to explain the deregulatory action taken (or regulatory move avoided), its consequence, and the process by which big financial firms and their political allies maneuvered to achieve their deregulatory objective. In Part II, we present data on financial firms’ campaign contributions and disclosed lobbying investments. The aggregate data are startling: The financial sector invested more than $5.1 billion in political influence purchasing over the last decade. The entire financial sector (finance, insurance, real estate) drowned political candidates in campaign contributions over the past decade, spending more than $1.7 billion in federal elections from 1998-2008. Primarily reflecting the balance of power over the decade, about 55 percent went to Republicans and 45 percent to Democrats.

Democrats took just more than half of the financial sector’s 2008 election cycle contributions. The industry spent even more—topping $3.4 billion—on officially registered lobbying of federal officials during the same period. During the period 1998-2008: • Accounting firms spent $81 million on campaign contributions and $122 million on lobbying; • Commercial banks spent more than $155 million on campaign contributions, while investing nearly $383 million in officially registered lobbying; • Insurance companies donated more than $220 million and spent more than $1.1 billion on lobbying; • Securities firms invested nearly $513 million in campaign contributions, and an additional $600 million in lobbying. All this money went to hire legions of lobbyists. The financial sector employed 2,996 lobbyists in 2007. Financial firms employed an extraordinary number of former government officials as lobbyists. This report finds 142 of the lobbyists employed by the financial sector from 1998- 2008 were previously high-ranking officials or employees in the Executive Branch or Congress.

* * *

These are the 12 Deregulatory Steps to Financial Meltdown:

1. Repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act and the Rise of the Culture of Recklessness

The Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 formally repealed the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 (also known as the Banking Act of 1933) and related laws, which prohibited commercial banks from offering investment banking and insurance services. In a form of corporate civil disobedience, Citibank and insurance giant Travelers Group merged in 1998—a move that was illegal at the time, but for which they were given a two-year forbearance—on the assumption that they would be able to force a change in the relevant law at a future date. They did. The 1999 repeal of Glass-Steagall helped create the conditions in which banks invested monies from checking and savings accounts into creative financial instruments such as mortgage-backed securities and credit default swaps, investment gambles that rocked the financial markets in 2008.

2. Hiding Liabilities: Off-Balance Sheet Accounting

Holding assets off the balance sheet generally allows companies to exclude “toxic” or money-losing assets from financial disclosures to investors in order to make the company appear more valuable than it is. Banks used off-balance sheet operations—special purpose entities (SPEs), or special purpose vehicles (SPVs)—to hold securitized mortgages. Because the securitized mortgages were held by an off-balance sheet entity, however, the banks did not have to hold capital reserves as against the risk of default—thus leaving them so vulnerable. Off-balance sheet operations are permitted by Financial Accounting Standards Board rules installed at the urging of big banks. The Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association and the American Securitization Forum are among the lobby interests now blocking efforts to get this rule reformed.

3. The Executive Branch Rejects Financial Derivative Regulation

Financial derivatives are unregulated. By all accounts this has been a disaster, as Warren Buffet’s warning that they represent “weapons of mass financial destruction” has proven prescient. Financial derivatives have amplified the financial crisis far beyond the unavoidable troubles connected to the popping of the housing bubble. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has jurisdiction over futures, options and other derivatives connected to commodities. During the Clinton administration, the CFTC sought to exert regulatory control over financial derivatives. The agency was quashed by opposition from Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and, above all, Fed Chair Alan Greenspan. They challenged the agency’s jurisdictional authority; and insisted that CFTC regulation might imperil existing financial activity that was already at considerable scale (though nowhere near present levels). Then-Deputy Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers told Congress that CFTC proposals “cas[t] a shadow of regulatory uncertainty over an otherwise thriving market.”

4. Congress Blocks Financial Derivative Regulation

The deregulation—or non-regulation—of financial derivatives was sealed in 2000, with the Commodities Futures Modernization Act (CFMA), passage of which was engineered by then-Senator Phil Gramm, R-Texas. The Commodities Futures Modernization Act exempts financial derivatives, including credit default swaps, from regulation and helped create the current financial crisis.

5. The SEC’s Voluntary Regulation Regime for Investment Banks

In 1975, the SEC’s trading and markets division promulgated a rule requiring investment banks to maintain a debt-to-net-capital ratio of less than 12 to 1. It forbid trading in securities if the ratio reached or exceeded 12 to 1, so most companies maintained a ratio far below it. In 2004, however, the SEC succumbed to a push from the big investment banks—led by Goldman Sachs, and its then-chair, Henry Paulson—and authorized investment banks to develop their own net capital requirements in accordance with standards published by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. This essentially involved complicated mathematical formulas that imposed no real limits, and was voluntarily administered. With this new freedom, investment banks pushed borrowing ratios to as high as 40 to 1, as in the case of Merrill Lynch. This super-leverage not only made the investment banks more vulnerable when the housing bubble popped, it enabled the banks to create a more tangled mess of derivative investments—so that their individual failures, or the potential of failure, became systemic crises. Former SEC Chair Chris Cox has acknowledged that the voluntary regulation was a complete failure.

6. Bank Self-Regulation Goes Global: Preparing to Repeat the Meltdown?

In 1988, global bank regulators adopted a set of rules known as Basel I, to impose a minimum global standard of capital adequacy for banks. Complicated financial maneuvering made it hard to determine compliance, however, which led to negotiations over a new set of regulations. Basel II, heavily influenced by the banks themselves, establishes varying capital reserve requirements, based on subjective factors of agency ratings and the banks’ own internal risk-assessment models. The SEC experience with Basel II principles illustrates their fatal flaws. Commercial banks in the United States are supposed to be compliant with aspects of Basel II as of April 2008, but complications and intra-industry disputes have slowed implementation.

7. Failure to Prevent Predatory Lending

Even in a deregulated environment, the banking regulators retained authority to crack down on predatory lending abuses. Such enforcement activity would have protected homeowners, and lessened though not prevented the current financial crisis. But the regulators sat on their hands. The Federal Reserve took three formal actions against subprime lenders from 2002 to 2007. The Office of Comptroller of the Currency, which has authority over almost 1,800 banks, took three consumer-protection enforcement actions from 2004 to 2006.

8. Federal Preemption of State Consumer Protection Laws

When the states sought to fill the vacuum created by federal nonenforcement of consumer protection laws against predatory lenders, the feds jumped to stop them. “In 2003,” as Eliot Spitzer recounted, “during the height of the predatory lending crisis, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency invoked a clause from the 1863 National Bank Act to issue formal opinions preempting all state predatory lending laws, thereby rendering them inoperative. The OCC also promulgated new rules that prevented states from enforcing any of their own consumer protection laws against national banks.”

9. Escaping Accountability: Assignee Liability

Under existing federal law, with only limited exceptions, only the original mortgage lender is liable for any predatory and illegal features of a mortgage—even if the mortgage is transferred to another party. This arrangement effectively immunized acquirers of the mortgage (“assignees”) for any problems with the initial loan, and relieved them of any duty to investigate the terms of the loan. Wall Street interests could purchase, bundle and securitize subprime loans—including many with pernicious, predatory terms—without fear of liability for illegal loan terms. The arrangement left victimized borrowers with no cause of action against any but the original lender, and typically with no defenses against being foreclosed upon. Representative Bob Ney, R-Ohio—a close friend of Wall Street who subsequently went to prison in connection with the Abramoff scandal—was the leading opponent of a fair assignee liability regime.

10. Fannie and Freddie Enter the Subprime Market

At the peak of the housing boom, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were dominant purchasers in the subprime secondary market. The Government-Sponsored Enterprises were followers, not leaders, but they did end up taking on substantial subprime assets—at least $57 billion. The purchase of subprime assets was a break from prior practice, justified by theories of expanded access to homeownership for low-income families and rationalized by mathematical models allegedly able to identify and assess risk to newer levels of precision. In fact, the motivation was the for-profit nature of the institutions and their particular executive incentive schemes. Massive lobbying—including especially but not only of Democratic friends of the institutions—enabled them to divert from their traditional exclusive focus on prime loans. Fannie and Freddie are not responsible for the financial crisis. They are responsible for their own demise, and the resultant massive taxpayer liability.

11. Merger Mania

The effective abandonment of antitrust and related regulatory principles over the last two decades has enabled a remarkable concentration in the banking sector, even in advance of recent moves to combine firms as a means to preserve the functioning of the financial system. The megabanks achieved too-big-to-fail status. While this should have meant they be treated as public utilities requiring heightened regulation and risk control, other deregulatory maneuvers (including repeal of Glass-Steagall) enabled these gigantic institutions to benefit from explicit and implicit federal guarantees, even as they pursued reckless high-risk investments.

12. Rampant Conflicts of Interest: Credit Ratings Firms’ Failure

Credit ratings are a key link in the financial crisis story. With Wall Street combining mortgage loans into pools of securitized assets and then slicing them up into tranches, the resultant financial instruments were attractive to many buyers because they promised high returns. But pension funds and other investors could only enter the game if the securities were highly rated. The credit rating firms enabled these investors to enter the game, by attaching high ratings to securities that actually were high risk—as subsequent events have revealed. The credit ratings firms have a bias to offering favorable ratings to new instruments because of their complex relationships with issuers, and their desire to maintain and obtain other business dealings with issuers. This institutional failure and conflict of interest might and should have been forestalled by the SEC, but the Credit Rating Agencies Reform Act of 2006 gave the SEC insufficient oversight authority. In fact, the SEC must give an approval rating to credit ratings agencies if they are adhering to their own standards—even if the SEC knows those standards to be flawed.

* * *

Wall Street is presently humbled, but not prostrate. Despite siphoning trillions of dollars from the public purse, Wall Street executives continue to warn about the perils of restricting “financial innovation”—even though it was these very innovations that led to the crisis. And they are scheming to use the coming Congressional focus on financial regulation to centralize authority with industry- friendly agencies. If we are to see the meaningful regulation we need, Congress must adopt the view that Wall Street has no legitimate seat at the table. With Wall Street having destroyed the system that enriched its high flyers, and plunged the global economy into deep recession, it’s time for Congress to tell Wall Street that its political investments have also gone bad. This time, legislating must be to control Wall Street, not further Wall Street’s control. This report’s conclusion offers guiding principles for a new financial regulatory architecture.

20,000 Americans Lose Their Job Each day but we Still Bailout Wall Street and Banks

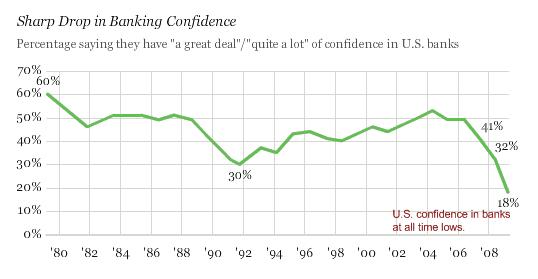

Four banks and one credit institution failed on Friday. This is now becoming a common Friday ritual. On February 13 four banks were also taken over by the FDIC. Multiple bank failures on one day are now growing in size. Yet the FDIC is quickly blazing through their insurance fund and soon, the taxpayer is going to be paying the bill. The American taxpayer is already bailing out many of the larger financial institutions. These are the 19 banks included in the smoke and mirrors government stress test. What a surprise that all banks looked fine especially since the U.S. Treasury allowed banks to self report on many items. 150 people were involved in examining trillions and trillions of dollars in assets. It was the ultimate bread and circus event for the masses.American households are quickly realizing that all the trillions committed to bailouts are essentially going to prop up the banking oligarchy that appears to be running the country. This is reflected in polling although the mainstream media hardly talks about this because they are hungry for advertising revenues which come from these sectors:

You would think that with only 18 percent of Americans having some confidence in their banking system that the media would be shedding a more critical eye on the banks. That is not case. And as I will show with the following four graphs, nearly 2 years into this financial crisis, the vast majority of Americans have not seen any noticeable help. A country with 24 million unemployed and underemployed citizens and we are asked to bailout the perpetrators of one of histories greatest debt bubbles.

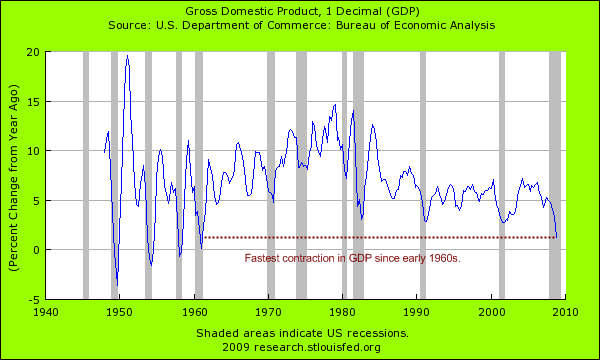

Gross Domestic Product

Gross domestic product is the aggregate figure of a nation’s economic vitality. Gross domestic product can be broken down as follows:

GDP = consumption + gross investment + government spending + (exports - imports)

A large part of our GDP comes from consumption (over two-thirds). If you stop and think about this, a country that spends more than it earns is bound to get into economic trouble eventually. And this balance completely shifted in the last 30 years. This credit bubble started 30 years ago and you will see that in a subsequent graph. The fairytale that was pushed onto the American public was that it was okay to consume more than it produced. In fact, not only was this okay but it was okay to consume and do this with debt. It is fascinating that we call this mess the credit bubble when in reality, it is a debt bubble. How often have you heard politicians, Wall Street, or the mainstream media call this the debt bubble? George Orwell would be proud.

Now the chart above is important. As you can see, on a year over year basis GDP is contracting at the fastest pace since the early 1960s. Most bailout recipients are betting (hoping) there will be a second half recovery because there is a growing populist anger against the banks and Wall Street and rightfully so.

And going back to our initial equation, consumption has been decreasing while government spending is attempting to make up for that fall in the equation. We are also exporting less and definitely importing less as measured by traffic at our busiest ports.

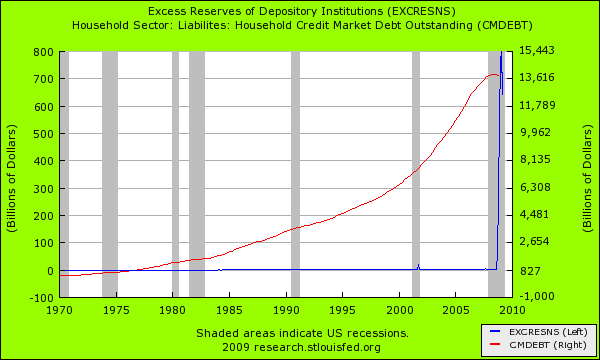

Household Debt and Excess Reserves

The above chart is rather telling. As you can see for yourself, household debt has been increasing by leaps and bounds for the past 30 years. It has gotten to the point where households have as much debt as our nation’s annual GDP. We have been spending our way to prosperity (or at least the illusion of it). I’ve also included in the chart part of the nice little gift we are handing out to banks. If you recall, the entire purpose of the bailout was to help American families have access to credit. That was the argument at least.

The chart above shows since the 1970s (and even before that) banks never carried any size of excess reserves. Why? They have been lending money out like maniacs for 40 years. All this money was handed out to consumers to spend and spend on things increasingly made abroad. We were told that manufacturing and making “things” was a waste of time and should be relegated to “third-world” countries. But recently, even banks don’t believe this.

The jump in excess reserves, money that was supposed to trickle down to American consumers is being hoarded to deal with problems on bank balance sheets. Ask yourself this, if banks were so healthy like the stress test told us, then why are they holding onto $700 billion in excess reserves? The answer of course is that they are not healthy and are looking out for themselves. The entire premise of bailing out the banks was false. The reason we bailed out the banks was to protect Wall Street and the banks. Period. It had nothing to do with protecting the American consumer who is already maxed out in debt as you can see from the chart above.

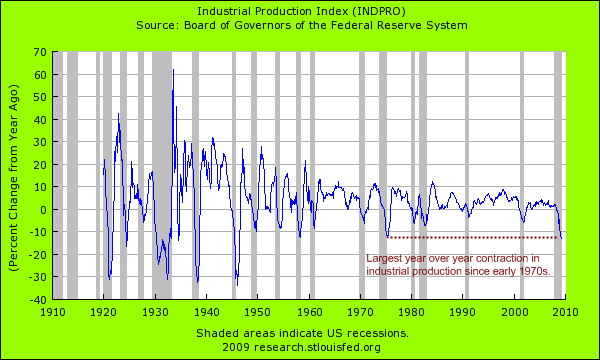

Industrial Production

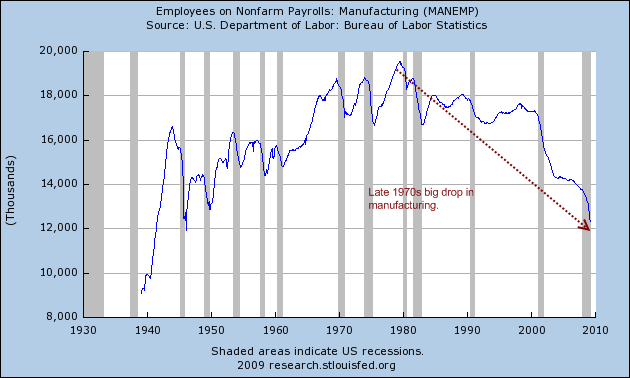

As the largest economy in the world, we still do produce a lot although as you can see from the above charts we have been consuming more and more. Industrial production is contracting at the fastest pace since the 1970s. The trouble with this is that in the 1970s, there was a legitimate reason for the decline in industrial production. That reason was we were shipping manufacturing jobs overseas:

So much of that fall in the 1970s had to do with this. But now, the contraction is largely due to the economic consequences of spending too much all fueled by debt. While Americans are now having to do more with less, banks (the select 19 at least) are having an unlimited line of credit to the U.S. government. Over the past few months, 20,000 Americans are losing their jobs per day. Many are realizing they have no safety net yet watch their tax dollars go to pay executive compensation and bailout banking giants who profited by creating the biggest debt bubble ever known.

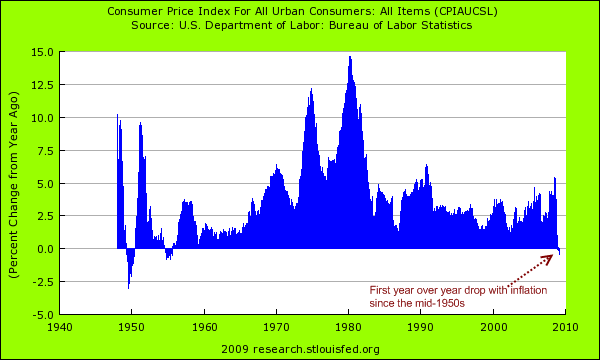

Inflation and Deflation

The menace of deflation is making the rounds. Cheaper homes. Automobiles that now cost thousands of dollars less because of falling demand. Cheaper fuel. Stagnant wages. All these are signs of deflation. As the chart above will show, this is the first time we have seen a year over year drop in the CPI since the mid-1950s. We keep hearing that eventually, we will see inflation because of all the bailouts. That would only be true if banks weren’t hoarding the money to prop each other up. The money would have to make it into the hands of consumers to cause any inflation. Yet that is not happening. Also, since the crisis started nearly $50 trillion in global wealth has evaporated. So even though we are committing approximately $13 trillion to bailout our economy (largely Wall Street and banks) there has been more money destruction than money creation. So that is why we have yet to see any signs of inflation.

The disturbing path we are following is largely what Japan did in bailing out their banking system. They now have some of the largest government debt burdens in relation to their GDP because of these bailouts. And what was the result nearly 20 years later? A stagnant economy with their stock markets still at lows and their real estate market still near the bottom. Yet some people made out like bandits. These were those tied to the largest banks. Is this sounding familiar?

The bottom line is once Americans realize in mass that they are largely bailing out banks to save banks, not the country, they will start asking more important questions. And the above polls reflect this change. Yet watching the mainstream media you would not know this. Hearing politicians talk you would think that we are all for committing trillions to save Wall Street. The vast majority of Americans do not support these actions.

Just read what was released by New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo regarding Bank of America’s shotgun marriage to Merrill Lynch (the entire letter is worth a read):

“Despite the fact that Bank of America had determined that Merrill Lynch’s financial condition was so grave that it justified termination of the deal pursuant to the MAC clause, Bank of America did not publicly disclose Merrill Lynch’s devastating losses or the impact it would have on the merger. Nor did Bank of America disclose that it had been prepared to invoke the MAC clause and would have done so but for the intervention of the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve.

Lewis testified that the question of disclosure was not up to him and that his decision not to disclose was based on direction from Paulson and Bernanke: “I was instructed that ‘We do not want a public disclosure.”

Basically Ken Lewis, CEO of Bank of America did not have the guts to do what was right and the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve basically sacrificed the American taxpayer to save another crony bank. Ken Lewis wanted to back out because Merrill Lynch had horrific losses which made the deal a bad one. Yet the U.S. Treasury through Paulson realized that the only way they were going to get political power to save Merrill Lynch was if they linked it up to a large institution most Americans are familiar with. Bank of America. Lewis greedy and hungry naively jumped into the deal to own a Wall Street broker powerhouse and got screwed. Once he found out the fact that the firm had lied (shocker) about losses it was too late.

Once BofA had Merrill, Paulson basically told Lewis if he backed out he would be replaced. You keep hearing systemic risk non-sense but Lehman Brothers failed and we managed. Yet how could they allow one of their own to fail? This folks is how Americans are bailing out banks and Wall Street while each day 20,000 additional Americans become unemployed.

GM Bondholder Group Says Offer Isn’t 'Reasonable'

General Motors Corp. bondholders find the automaker’s offer to exchange their $27 billion in debt for equity unreasonable and said they should be treated more equitably with labor unions. “We believe the offer to be a blatant disregard of fairness for the bondholders who have funded this company and amounts to using taxpayer money to show political favoritism of one creditor over another,” the ad hoc committee of GM bondholders said today in a statement. Bondholders are being asked to swap all their claims for 10 percent of the equity in the reorganized company. The offer is contingent on cutting at least half of GM’s $20.4 billion of obligations to a United Auto Workers retiree-medical fund, known as a Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Association, through a debt- for-equity exchange that would give the VEBA as much as 39 percent of common stock in the Detroit-based carmaker.

Without an accord, bondholders face the uncertainty of bankruptcy, GM Chief Financial Officer Ray Young said today. At least 90 percent in principal amount of the notes must be exchanged by June 1 to satisfy the U.S. Treasury, GM said today in a statement. “This is an offer that’s designed to fail,” said Kip Penniman, an analyst at fixed-income research firm KDP Investment Advisors in Montpelier, Vermont. “To get 90 percent of them to agree to such a deal where there’s no cash, no other debt and pure equity while leaving the union VEBA arrangement unchanged from previous considerations is absurd.”

GM has received $15.4 billion in government aid and is trying to prove it’s viable, a U.S. requirement to keep the federal loans. The original loan terms called for GM to slash two-thirds of its bonds through an exchange offer and for the VEBA to reduce a cash contribution to $10.2 billion from $20.4 billion. The bondholder committee, whose members include San Mateo, California-based Franklin Resources Inc. and Loomis Sayles & Co. of Boston, has been in contact with about 100 institutions representing about $12 billion of GM bonds, according to a person familiar with the discussions. The committee plans to try to negotiate a better offer, said the person, who declined to be identified because the talks are private. GM has “limited” options to alter terms of the debt exchange and to consider the proposal as a “take it or leave it” offer wouldn’t be “too strong,” GM’s Young said today in an interview.

The automaker has been given few options by the U.S. government to expand bondholders’ stake beyond 10 percent of the proposed 60 billion in new GM shares or otherwise increase the offer, he said. Bondholders need to weigh what they are giving up under the offer against improved marketing spending for surviving GM brands, potential profitability of dealers and efficiency of manufacturing in the revamped company, Young said. The Obama administration’s auto task force ousted Chief Executive Officer Rick Wagoner last month, saying that GM’s plan to return to profit wasn’t aggressive enough, and ordered new CEO Fritz Henderson to cut the automaker’s debt by more than initially demanded. GM will be forced to go into a government- supported bankruptcy without deeper cost cuts from its creditors by June 1, the administration said.

“This offer demonstrates that the company and the auto task force, unfortunately, are pinning their hopes on an extremely risky and legally questionable turnaround in bankruptcy court, instead of engaging its lenders and workers in the very type of negotiations that could avoid such a fate,” the bondholders said in the statement. GM bondholders may fare worse in bankruptcy, according to Shelly Lombard, an analyst in Montclair, New Jersey for bond research firm Gimme Credit LLC. “You have a gun being put to your head saying that if you don’t take this, we have something that’s even worse for you,” Lombard said. “It looks like a raw deal for bondholders. I just don’t think they have the negotiating leverage to get anything better than what’s currently on the table.” GM’s $3 billion of 8.375 percent bonds due in 2033 rose 1.75 cents to 10.5 cents on the dollar, according to Trace, the bond-price reporting system of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. The debt yields about 78 percent.

Bondholders will be given 225 shares of GM common stock for each $1,000 in principal amount tendered and will also receive accrued interest in cash. The proposed debt exchange is also conditional on the U.S. Treasury agreeing to exchange 50 percent of its loans at June 1, estimated to be $10 billion, for stock. The VEBA and the U.S. Treasury would own about 89 percent of the common stock in the reorganized GM after their debt exchanges, the statement said. The remaining 1 percent of stock would be held by GM’s existing common shareholders. Before Wagoner was removed, GM had proposed that bondholders swap more than three-quarters of their stake for equity, according to a person familiar with the talks. That offer would have given bondholders 90 percent of the equity of the reorganized automaker and a combination of cash and new unsecured notes, the person said at the time.

Teenage pregnancy may be the answer to our mountain of debt

If you were looking for scary economic charts you could hardly do worse than dig out the one showing Britain’s national debt going back to the 19th century. There is a striking pattern – namely that throughout history the national debt is directly correlated with war. Every time there was a military skirmish, from the Napoleonic era to the wars of the 20th century, it pushed the public debt sharply higher. The apotheosis of this is the 1914-1940s period, when Britain’s net debt was catapulted into the stratosphere to pay for two world wars. Since then, there have been a few mounds and bumps as the debt went up and down to pay for a recession here or a downturn there but nothing to rival the monetary Matterhorn that has overshadowed modern UK accounts. Until now. The economic crisis will push up Britain’s public debt mountain by epochal proportions. Try as he might, the Chancellor could not hide the horrendous cost of this recession. If there was any doubt it is different from any previous recessions, that was dismissed by this week’s Budget. The fact is this: since Victorian times, whenever there was not a war on, Britain’s national debt sat near enough – and usually comfortably below – 50pc of gross domestic product. It is no coincidence that, when Gordon Brown laid down his now defunct fiscal rules, he ordained that net debt should be kept below 40pc of GDP.

However, as the Budget spelled out, the cost of the recession will push Britain’s public debt mountain up from below 40pc to 80pc of GDP. This, too, is likely to be over-optimistic, based as it is on an unrealistic assumption of when the economy will recover. More likely is that the mountain climbs higher still, pushing through the 100pc mark for the first time since the late 1950s and early 1960s, when Britain was still paying off its wartime debts. What does all of this matter? Well, it means we can dismiss any prospect of a real economic feel-good factor returning for many, many years. A high national debt has two consequences: the first is that a sensible government must do whatever it can to start paying it back, either by cutting spending or raising taxes. Dig into the Budget’s detail and you see that after a couple more years of splurge the Government intends to cut spending in real terms by around 2.3pc in most of its departments, and anyone holding their breath for tax cuts should prepare for asphyxiation. The second consequence is that interest rates will start to rise, whatever happens to inflation. Higher national debt brings higher debt servicing costs, both because the amount to be repaid is higher and because investors will become more wary of lending to the UK. You can see it already, as gilt yields have jolted higher and higher since the Chancellor sat down and the full horror of those Budget figures was revealed to the markets. It means that should any green shoots of recovery appear, they will be stamped down on repeatedly by the Treasury as it seeks to put right this mess.

Should the Chancellor not impose such discipline he will be punished as investors abandon UK Government debt and, potentially, force a buyers’ strike in the gilts market. This would mean the Labour Government would, in time-honoured fashion, end its tenancy with a visit to the International Monetary Fund. One wonders whether Alistair Darling, in his visit to Washington this weekend, is readying the ground for just such a moment. Despite all this gloom, there are two glimmers of consolation. First is that the UK is not alone. In other words, sell British debt if you like, but whose will you buy in its place? Britain’s accounts are appalling but the economic crisis is global: everyone’s public debt is likely to climb at a similar rate. The second glimmer is to be found in an obscure chart in the Budget documentation, which shows that Britain’s birth rate is rather greater than any of its other major developed nation counterparts. In other words, we do not face the demographic crisis likely to ravage Europe and Japan. So, cry as we might about the social issues our nation of single mothers is causing us, their fecundity will at least provide us with a big enough future generation to help pay all this debt off. Who would have thought that teenage pregnancy may prove the answer to the biggest fiscal dilemma in peacetime history?

A second wave of home foreclosures is ahead, Fed economist says

A second, punishing wave of home foreclosures is poised to strike just as the subprime mortgage mess ebbs, an economist in Kansas City said Thursday. Kelly Edmiston, senior economist for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, dropped that unwelcome forecast at the Fed’s Money Smart Day program. “I don’t expect the foreclosure problem to get much better in the next couple of years. In fact, it may well get worse,” Edmiston said. Blame the widening recession, persistent unemployment and exotic mortgages that emerged alongside the boom in subprime lending to less creditworthy homebuyers. Lenders laid the groundwork for this second foreclosure wave in 2005 and 2006, Edmiston said. Those years saw a surge in mortgages on which borrowers were required to make relatively small monthly payments for the first five years.

It was the height of the housing bubble, and buyers turned to such loans, called interest-only mortgages and payment-option adjustable-rate mortgages, as one way to jump into the runaway market.

Those low house payments are poised to reset to much higher levels in 2010 and 2011 and push more owners out of their homes, Edmiston said. Subprime mortgages fueled their own foreclosure crisis earlier because their payments typically reset after only two years instead of five. According to Edmiston, these next mortgage resets will mean even larger leaps in house payments than the subprime mortgage resets that forced one in five subprime borrowers with adjustable interest rates into foreclosure. Kansas City’s housing market may suffer less from this second wave, Edmiston said. He said interest-only and payment-option mortgages weren’t as widely used here because housing remained more affordable than in California, Florida and similar markets.

The weak economy, however, is adding to this second foreclosure wave by pushing traditional mortgage customers into default, Edmiston said. That combination leads him to suspect that the foreclosure problem isn’t about to go away. Edmiston showed his audience maps of rising foreclosure rates in Independence, Lee’s Summit, Lenexa and Merriam as evidence of the broadening foreclosure problem. The subprime debacle had largely struck lower-income and higher-minority population centers, he said. One hopeful thought: Edmiston said housing prices may be near a bottom. And with many potential buyers on the sidelines, prices could jump if most of those buyers start bidding at roughly the same time. It won’t be enough, however, to stem area foreclosure rates for the next couple of years, he said.

Warning over UK derivatives backlash

London risks further damage as a financial centre if policymakers rush to regulate the over-the-counter derivatives markets without distinguishing between instruments that helped cause the financial crisis and those that did not, a report commissioned by the City of London Corporation said on Monday. The report, prepared by consultancy Bourse Consult, will urge regulators not to “throw the baby out with the bathwater” amid recent calls for OTC – or privately-negotiated – derivatives markets to be subjected to greater clearing and regulatory scrutiny. The warning is a sign that players in OTC derivatives, one of the largest parts of financial services, are starting to lobby against what they see as the potential for a regulatory backlash that could inflict serious collateral damage to the City, home to the bulk of OTC derivatives activity.

The recent G20 meeting pledged to “promote the standardisation and resilience of credit derivatives markets, in particular through the establishment of central clearing counterparties subject to effective regulation and supervision”. London accounts for 43 per cent of the value of OTC derivatives traded, with the US on 24 per cent, Bourse Consult said. It rejected the widely-held assumption that derivatives in general were to blame for the crisis, arguing that critics fail to distinguish between derivatives that functioned normally – such as foreign exchange and interest rate swaps - and collateralised debt obligations and other structured products. “The credit derivatives which were traded most heavily on the OTC derivatives markets were CDS. There is very little evidence to suggest that these contributed in any significant way to the crisis,” the report said.

It said the push by regulators and legislators for such instruments to become more transparent had become “a highly politicised issue”. “It seems inevitable that CDS and possibly even the whole OTC derivatives market are going to be much more heavily regulated as a result of political pressure that ‘something needs to be done’ about the OTC market. “In accepting the inevitable additional regulation that will come, it is important that the very successful OTC derivatives market is not crushed in the process,” wrote the report’s author, Lynton Jones, a former chief executive of the London-based International Petroleum Exchange. He said the derivative at the centre of the crisis were collateralised debt obligations, which were used as part of the mortgage securitisation process by banks. The problems in the CDO market “totally outweighed the perceived problems of CDS”.