"Widow & boy rolling papers for cigarettes in a dirty New York tenement"

Ilargi: While it's true that the Federal Reserve didn't say it in so many words, that's only because it's not capable of saying anything at all in only so many words. Perhaps that's due to Greenspan's Oracle heritage. Still, between the lines the Fed did say it: it has given up on an imminent recovery of the American economy, and most of all, it has given up on the American people. (Caveat: to give up on something one must at one time have cared for it to begin with.)

The Fed's recent and persistent rosy predictions of a 4% or so economic growth for the US have become ridiculously untenable, and Bernanke et al wish that to be known. That can only mean one thing: they see a lot more trouble on the horizon, and wish to cover their behinds and reputations. In true Oracle fashion, the wording itself has changed from "moderate" growth in June to "more modest than anticipated" yesterday. Here's thinking that Bernanke's definition of "exceptionally low rates for an extended period" doesn't apply only to interest rates, it's equally valid for economic growth.

For many pundits, the only conclusion that can be drawn from this is that the Fed will "ease" more, and is preparing to use its "vast range" of monetary tools to fight the depression everyone still prefers to call a recession. But, assuming for a moment that the Fed has any intention of doing so, what then are these tools? Note that even as the wording of the expectations has gone sharply downward, all the board has said is that it will replace some $20 billion per month in maturing agency and mortgage backed securities with Treasuries, so it will not hold less than $2.05 trillion in such paper.

Does that help the economy at large? No, of course not. And this is where you can see that the Fed has given up on the American people. Actions such as these help the banks, and the banks only. That is what the Fed has adopted as its first and singular priority: to keep the bankrupt banking system propped up, and to such an extent that banks not only look healthy, they even get to dole out gigantic sums in bonuses. The $2.05 trillion "bottom" announced yesterday is there to make sure that the banks won't suffocate from the toxic fumes their very own "assets" are spreading.

And it could perhaps work, or, more correctly, might have worked. If only sufficient economic growth would have enabled the continuation of the scheme. Alas, even the imitation Oracles can't go any further, or do any better, than "more modest than anticipated". That threatens to bring down the foundations of all western governments' financial strategies, and America's most of all. All the times that Tim Geithner has declared that there was no need for a plan B, because a plan of his couldn't fail, strong economic growth was an indispensable element in the plans. Bernanke has now admitted that such growth will not be available. Count your blessings.

All the talk around yesterday's Fed announcement focuses on quantitative easing, QE2. Which is somewhat bewildering, given the utter failure of QE1 in the US. The only thing QE1 achieved, again, was to prop up banks. Yes, that succeeded. But the goal was, or so we were led to believe, that the trillions the Fed injected would percolate through to the real economy.

That didn't happen. And no, that is no surprise to the Fed. Remember, if you will, that Bernanke sometime last year announced that the Fed would from there on in pay banks interest on their excess reserves (reserves they're not legally required to hold). These reserves, which banks hold with the Fed, have gone from $1-2 billion a few years ago to over $1 trillion today. And the Fed pays interest over them. If ever you wonder if maybe the Fed and the Treasury aren't looking out for your best interests after all, you may want to wonder why Bernanke doesn't simply announce that those interest payments will be gone by tomorrow morning. That could make the banks lend out the money, couldn't it?

Well, not so fast. There are other things that are wrong with the entire quantitative easing concept that hardly anyone cares to look at. The Pragmatic Capitalist has a great explanation:

Quantitative Easing: "The Greatest Monetary Non-Event"There is, perhaps, no greater misunderstanding in the investment world today than the topic of quantitative easing. After all, it sounds so fancy, strange and complex. But in reality, it is quite a simple operation. JJ Lando, a bond trader at Goldman Sachs, has eloquently described QE:“In QE, aside from its usual record keeping activities, the Fed converts overnight reserves into treasuries, forcing the private sector out of its savings and into cash. This is just a large-scale version of the coupon-passes it needed to do all along. Again, they force people out of treasuries and into cash and reserves.”Some investors prefer to call it “money printing” or “stimulative monetary policy”. Both are misleading and the latter is particularly misleading in the current market environment. First of all, the Fed doesn’t actually “print” anything when it initiates its QE policy. The Fed simply electronically swaps an asset with the private sector. In most cases it swaps deposits with an interest bearing asset. They’re not “printing money” or dropping money from helicopters as many economists and pundits would have you believe. It is merely an asset swap.[..]

The most glaring example of failed QE is in Japan in 2001. Richard Koo refers to this event as the "greatest monetary non-event". In his book, The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics, Koo confirms what the BIS states above:"In reality, however, borrowers – not lenders, as argued by academic economists – were the primary bottleneck in Japan’s Great Recession. If there were many willing borrowers and few able lenders, the Bank of Japan, as the ultimate supplier of funds, would indeed have to do something. But when there are no borrowers the bank is powerless."[..]

No, no – Mr. Bernanke hasn’t failed. He just hasn’t tried hard enough….But perhaps the reader believes Japan is different and not applicable. This is a reasonable objection. So why don’t we look at the evidence from the last round of QE here in the USA. Since Ben Bernanke initiated his great monetarist gaffe in 2008 there has been almost no sign of a sustainable private sector recovery.

Mr. Bernanke’s new form of trickle down economics has surely fixed the banking sector (or at least bought some time), but the recovery ended there. It did not spread to Main Street. We would not even be having this discussion if we were in the midst of a private sector recovery. [..]

What is equally interesting (in addition to the fact that QE is not economically stimulative) with regards to this whole debate is that this policy response in time of a balance sheet recession is not actually inflationary at all. With the government merely swapping assets they are not actually "printing" any new money. In fact, the government is now essentially stealing interest bearing assets from the private sector and replacing them with deposits.

This might have made some sense when the credit markets were frozen and bank balance sheets were thought to be largely insolvent, but now that the banks are flush with excess reserves this policy response would in fact be deflationary- not inflationary. Why would we remove interest bearing assets from the private sector and replace them with deposits when history clearly shows that this will not stimulate borrowing?

Ilargi: So, there's no printing, and it's therefore not inflationary. Most of all, this is because nothing reaches the real economy. Bernanke's interest payments on excess reserves guarantee this outcome. What money banks do engage outside the Fed's vaults, they use for gambling on derivatives etc. Goldman made over a third of its profits last year from derivatives. And if these activities go awry, there's always the excess reserves to tap into. Get some at 0% (or close) at the discount window and get back to the gaming table. The 2010 US financial system in a nutshell.

Still, the key sentence above when it comes to the real economy is from Richard Koo: ... when there are no borrowers the bank is powerless .... This -crucial- statement appears again this morning in a piece from Rex Nutting at Marketwatch:

Monetary policy in a time of deleveragingWho cares what it costs to borrow when no one wants to take out a loan?[..]

The Fed has [..] flooded the economy with hundreds of billions of dollars. Instead of putting it to work, the banks have taken the Fed's money and parked it. [..]

... no one wants to borrow, and that's the biggest problem in getting the economy moving again.

The economy needs money to grow, and money is created by borrowing. No borrowing, no money growth. No money growth, no economic growth. No economic growth, no jobs.

Even 0% loans aren't attractive when you're deleveraging, when you're trying to work off the hangover that inevitably follows a binge of borrowing.

"And there isn't a damn thing Chairman Bernanke and company can do about it," says economist Stephen Stanley of Pierpont Securities.

Ilargi: Not a bad analysis, though of course it's simply not true that "The Fed has flooded the economy with hundreds of billions of dollars". . The Fed has flooded the banking system with all that money, but the banking system is not the same as the economy, even if the Geithners and Bernankes of this world would like you to think so, and are quite successful in convincing most people of this.

The take away from Nutting's piece is, even though we think we already know it, that money in our societies is created when people borrow it. It's then that a bank can create, for instance in the case of a mortgage, $250,000 with a keystroke. That's how we literally "make money". The Fed can do what it will, but if you're not going out there to get that loan, no money is created that actually enters the economy. No matter how many trillions the Fed hands over to Wall Street, it won’t go anywhere until you apply for a loan. Which, in today's circumstances, will then mostly be denied. Isn't the irony spectacularly appealing?

Craig Torres and Vivien Lou Chen at Bloomberg have a few more observations from the same Stephen Stanley Rex Nutting quotes in the article above, as well as a bit more on Bernanke's Oracle style:

Fed Reverses Exit Plans, Sets $2 Trillion Floor for Holdings"There is absolutely zero evidence that if you let the balance sheet run down $10 billion to $15 billion a month that it would be a binding restraint on the economy," said Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Pierpont Securities [..]

"They have given us no evidence why quantitative easing works," Stanley said.

Some observers said yesterday’s decision took them by surprise after Bernanke and other officials in recent weeks maintained their outlook for a pickup in the economy over the next year. While weakness in housing and commercial real estate will restrain the recovery, and the job market’s "slow recovery" weighs on consumers, "rising demand from households and businesses should help sustain growth," Bernanke said in an Aug. 2 speech in Charleston, South Carolina.

"It seems like communications is a problem, particularly around turning points," said Timothy Duy, a University of Oregon economist who formerly worked at the U.S. Treasury Department. "It seems odd that 10 days ago you had a speech that hardly acknowledged the weakness of the recent data."

Ilargi: I think it should be obvious by now that that is exactly the kind of light in which to read yesterday's Fed announcement. Odd. But at the same time, it was quite the turnaround from all that's been said before, and right there lies the important bit. They've given up on the recovery, and to a much greater extent than they let on. Got to feed it to the people bite-size, that's politics for you. Makes you wonder how Obama and Geithner will spin it.

Don't forget that one of the policy requirements for the Federal Reserve is "maximum employment". And then look at what they're doing to achieve it. How will the president tell his people that no economic growth means no jobs?

One last thing: a huge chunk of the mortgage backed securities the Fed holds (some $1,25 trillion of them) originated with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. A "trick" very similar to the one that lets banks hold excess reserves at the Fed and get paid to do so, plays in the Fannie and Freddie universe. Where the Fed supposedly tries to support the economy through QE, but makes sure it can never work when it starts paying interest on reserves, the government makes sure the housing industry will not get back on its feet, simply by guaranteeing every single mortgage that's closed at inflated prices. Both "tricks" pretend to help the people, but both in the end only help to support a broke banking system. And it's impossible to keep up the illusion that none of these smart people have figured that one out.

Fannie Mae belongs to the government. Fannie Mae also has started advertising $1000 down mortgage loans in select parts of the US. Granted, it's a last stage of desperation move, but the fact that it's even considered is what tells us the story of how our "leaders" see the world around them. On the one hand, you’d be inclined to think that it's a good thing the phony facade is about to fall, but on the other you quickly realize who will be the victims once that happens.

And then you need to ask: what are those mortgage backed securities the Fed holds really worth, and who will eventually make up for the difference between face value and actual worth?

Look, mortgage rates are at record lows. And so are pending home sales. Combine those two, and you have all you need to know about the future of the American economy. It really is that simple.

If no-one's borrowing, the overall money supply goes down. That spells deflation, and the Fed is powerless against it. It can't force you to borrow. And if no economic growth materializes, you're not going to increase borrowing. Because you'll be losing your jobs, or famliy, friends, neighbors will, and you’ll be forewarned.

And they know it too, Bernanke and Geithner. The Fed doesn't support you, the American people, it supports the zombie banking system at your cost. Seen from that particular angle, by the way, it's doing a great job. I’ll leave it up to you to decide where the Treasury, and the US government in general, stand on this. Think Fannie and Freddie.

Fed Reverses Exit Plans, Sets $2 Trillion Floor for Holdings

by Craig Torres and Vivien Lou Chen - Bloomberg

The Federal Reserve reversed plans to exit from aggressive monetary stimulus and decided to keep its bond holdings level to support an economic recovery it described as weaker than anticipated. Central bankers meeting yesterday adopted a $2.05 trillion floor for their securities portfolio, pivoting toward a quantitative target for monetary policy. Treasuries surged and stocks pared losses as some investors judged the decision opened the door to a resumption of large-scale asset purchases.

"The Fed is cognizant the recovery has lost some momentum and it is still willing to intervene," said Paul Ballew, a former Fed economist and a senior vice president at Nationwide Mutual Insurance Co. in Columbus, Ohio. "We always thought the exit strategy would be challenging. If you’re at the Fed, it’s proven to be more problematic than what you thought."

Officials directed the New York Fed’s trading desk to reinvest what economists estimate will be $15 billion to $20 billion a month in maturing agency and mortgage-backed securities back into U.S. Treasuries. The purchases will help keep Treasury yields and mortgage costs low and prevent the level of monetary stimulus from shrinking further. "They are now targeting a balance-sheet level, and the fact they are targeting the balance sheet is new," said Julia Coronado, a senior U.S. economist at BNP Paribas in New York who worked on the Fed Board staff for seven years. Any further easing "will likely come in the form of a higher balance sheet and investment in Treasuries."

Stocks Drop

The dollar rose 0.8 percent against the euro today, climbing to $1.3071 at 9:56 a.m. in London. Stocks fell, with the Stoxx Europe 600 Index dropping 0.9 percent and the MSCI Asia Pacific Index losing 1.6 percent. Standard & Poor 500’s index futures decreased 0.9 percent. Yields on U.S. 10-year notes yesterday dropped to an 18- month low and closed at 2.76 percent in late New York trading, down 7 basis points. A basis point is 0.01 percentage point.

U.S. central bankers came to their August meeting with a series of reports that pointed to slowing growth. U.S. companies added 71,000 workers to private payrolls in July, less than forecast by economists, and June gains were revised down to 31,000. The unemployment rate stayed at 9.5 percent. The jobless rate has sapped confidence, reducing consumer spending to a 1.6 percent annual rate in the second quarter, about half the average pace in the last expansion. U.S. companies don’t have much room to raise prices in the face of weak demand, keeping inflation low.

Risk Assets

The Fed’s decision yesterday may not succeed in bringing down unemployment even as it supports "risk assets," said Anthony Crescenzi at Pacific Investment Management Co., manager of the world’s biggest bond fund. Those jobs "won’t be recovered easily, certainly not by adding a couple hundred billion dollars into the banking system," Crescenzi said in an interview on Bloomberg Television. At the same time, "low volatility tends to be good for the interest-rate climate. It does push investors out the risk spectrum generally. That tends to be good for risk assets."

Aeropostale Inc., a retailer to teenagers whose sales rose in July at one-seventh the pace analysts predicted, said changing consumer preferences and a "challenging" retail environment hampered spending. Sales at J.C. Penney Co., a department-store chain, fell 0.6 percent last month.

Committee Statement

"The pace of recovery in output and employment has slowed in recent months," the Federal Open Market Committee said in its statement yesterday. "Measures of underlying inflation have trended lower in recent quarters." The personal consumption expenditures price index, minus food and energy, rose at a 1.4 percent rate for the 12 months ending June, below the 1.7 percent to 2 percent annual rate Fed officials view as preferable, according to their June forecasts.

The Fed left the overnight interbank lending rate target in a range of zero to 0.25 percent, where it’s been since December 2008, and repeated a pledge to keep rates low "for an extended period." The risk faced by the Fed is that growth slows to a pace that leaves unemployment high "as far as the eye can see," said Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in New York. That could increase the risk of deflation, or a general decline in prices that saps consumer spending and corporate profits and increases the value of debt.

‘More Worried’

"It is possible that they are just getting more worried about whether we are getting a rebound and a strong cyclical lift," Feroli said. Feroli and other economists said they were puzzled by the Fed’s choice of a $2 trillion target for its portfolio and said the central bank hasn’t explained how such a goal would "help support the economic recovery," as its statement said.

"There is absolutely zero evidence that if you let the balance sheet run down $10 billion to $15 billion a month that it would be a binding restraint on the economy," said Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Pierpont Securities LLC in Stamford, Connecticut. Until now, Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke has deployed what he called "credit easing," using backstops such as the Commercial Paper Funding Facility and purchases of $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities to lean against higher credit costs for home buyers and U.S. corporations as investors shunned risk.

Balance Sheet Swells

The Fed’s total assets, which include loans and securities other than those used for monetary-policy operations, rose to $2.33 trillion last week from $878 billion at the start of 2007. Even so, Fed officials never had a formal target for the balance sheet level. "They have given us no evidence why quantitative easing works," Stanley said. Some observers said yesterday’s decision took them by surprise after Bernanke and other officials in recent weeks maintained their outlook for a pickup in the economy over the next year.

While weakness in housing and commercial real estate will restrain the recovery, and the job market’s "slow recovery" weighs on consumers, "rising demand from households and businesses should help sustain growth," Bernanke said in an Aug. 2 speech in Charleston, South Carolina. "It seems like communications is a problem, particularly around turning points," said Timothy Duy, a University of Oregon economist who formerly worked at the U.S. Treasury Department. "It seems odd that 10 days ago you had a speech that hardly acknowledged the weakness of the recent data."

Monetary policy in a time of deleveraging

by Rex Nutting - MarketWatch

The Fed can't do much more to get credit flowing

The U.S. economy is on the edge of the cliff, threatening to plunge back into ruinous recession, but the worst part is that Washington won't do anything to stop it. The shame is that the Federal Reserve, the White House and Congress know they have a duty to act decisively, but they can't or won't under the mistaken notion that they've already done too much. We were sicker than they thought, but instead of increasing the dosage or looking for a better medicine, they've declared us to be cured.

Well, not cured, exactly, but as healthy as we're going to get. We'll just have to live with the nagging cough, the constant pain and the bleeding gums. Honestly, once you get used to it, you'll barely even notice 8% unemployment and falling living standards. To its credit, the Federal Reserve is at least keeping open the option of further stimulus to nudge the economy back to life. On Tuesday, the Fed said it would reinvest the proceeds of the maturing mortgage-backed bonds that it owns, thus preventing a stealth tightening of policy as the bonds run off.

For their part, the politicians in the White House and Congress have simply given up on any significant additional impetus for the economy. The Fed is also reluctant to act, in part because officials are worried that monetary policy has run up against the boundary of what it can accomplish.

Strange days

The essence of monetary policy is to influence the cost of borrowing by raising or lowering the interest rate that banks pay to borrow money from each other overnight, which is called the federal funds rate. The Fed can affect the money supply by manipulating this rate. Lower rates mean easier credit, which, in normal times, leads to economic growth and job creation as businesses and consumers borrow. But no one has to tell us that these are not normal times. Who cares what it costs to borrow when no one wants to take out a loan?

The Fed has lowered the federal funds rate essentially to zero, and it's flooded the economy with hundreds of billions of dollars. Instead of putting it to work, the banks have taken the Fed's money and parked it. The banks are nervous about lending it out, remembering what happened the last time. What's more, no one wants to borrow, and that's the biggest problem in getting the economy moving again. The economy needs money to grow, and money is created by borrowing. No borrowing, no money growth. No money growth, no economic growth. No economic growth, no jobs.

Instead, small businesses and consumers are busy paying down debt. Even 0% loans aren't attractive when you're deleveraging, when you're trying to work off the hangover that inevitably follows a binge of borrowing. "And there isn't a damn thing Chairman Bernanke and company can do about it," says economist Stephen Stanley of Pierpont Securities. The Fed is "pushing on a string," to quote one of the favorite metaphors of economists.

Easing not easy

The Fed has tried some fancy stuff to get around the problem of trying to get reluctant people to lend and borrow. It's tried quantitative easing, where the Fed goes into the market and buys securities such as Treasurys or mortgage-backed bonds. In exchange, the former owners of those securities now have cash burning a hole in their pockets. What to do with the proceeds? Splurge on consumer goods and stimulate the economy? Invest in some risky but potentially lucrative new venture that will create new jobs and economic growth? Or put it into a boring S&P 500 stock fund and buy more Treasurys? Guess what happened.

It's pretty clear that quantitative easing isn't a very efficient way to stimulate the economy. The Fed may try it again, but we shouldn't be surprised if it's ineffective. The Fed could just wait for households and small businesses to pare down their debts. Someday, they'll be ready, willing and able to borrow again. This is the point in the argument when John Maynard Keynes reminded us that, "in the long run, we are all dead."

The output gap -- the difference between where we are and where we should be -- isn't just lines on paper or theories in a classroom; it's real incomes that aren't earned, real goods and services that aren't produced or consumed, real dreams that aren't realized. It doesn't take a poet to know what happens to a dream deferred. Sometimes, it explodes. If the Fed's hands are tied, are we doomed to a lost decade of deferred dreams?

Happily, no. There is one group that's still able to borrow: the federal government, which could fill the gap temporarily by directly employing idle people to fulfill some of those deferred dreams. They could teach the children, heal the sick, build the infrastructure, discover new drugs, and invent new technologies. Unhappily, it's not going to happen.

Fed Shuns Passive Tightening, No QE2 in Sight

by Caroline Baum - Bloomberg

Downgrading its assessment of the pace of the economic recovery from "moderate" in June to "more modest than anticipated," the Federal Reserve took a symbolic step toward additional easing of monetary policy. The Fed will "keep constant" its securities portfolio, reinvesting the principal payments from agency and mortgage- backed securities in long-term Treasuries, according to the statement released following yesterday’s meeting.

The New York Fed, which conducts open market operations for the system, put out a qualifying statement saying its Treasury purchases would be concentrated in the two- to 10-year sector. Much of the economic commentary coming over the transom following yesterday’s meeting suggested the Fed had embarked on a second round of quantitative easing, familiarly known as QE2. How can it be quantitative easing when the quantity remains the same? What the Fed committed to, for the moment, is to maintain the size of its securities portfolio at $2.05 trillion rather than engage in passive tightening by allowing the balance sheet to shrink due to principal payments and maturing debt.

The Fed had been letting its mortgage portfolio shrink ever-so-slightly in recent months, even though the balance sheet has been stable since mid-April. Now the Fed will buy some $100 billion to $200 billion of Treasuries a year to offset the shrinkage, according to Neal Soss, chief economist at Credit Suisse in New York. That estimate is based on the normal pre-payment and amortization schedule on a similar-size mortgage portfolio.

No Exit

I have no idea whether the Fed will decide, next month or next year, to expand the size of its $2.3 trillion balance sheet. There was nothing in today’s statement to indicate what lies ahead. The Fed’s current assessment of the economy (not so hot) is backward-looking, based on the most recent economic data and just as reliable. The data were weak enough to "shake their confidence in the forecast," Soss says.

Earlier this year, the exit strategy was all the rage. Policy makers were focused on how to unwind the Fed’s bloated balance sheet without causing dislocations in the housing market and the economy at large. That noise you hear is the sound of the exit door being slammed shut. Yesterday, the Fed put us on notice that it’s getting out the WD-40 and oiling the hinges on the entry door. The decision to substitute Treasuries for maturing MBS will be welcome news to those Fed officials who want the central bank to get out of the credit business and return to a "Treasuries only" policy.

Trickle-Out Economics

Credit policy pertains to what the Fed buys. Quantitative easing tells us how much. QE1 led to an explosion in excess reserves, the reserves banks choose to hold over and above what they’re required to. They rose to $1 trillion from a pre-crisis range of $1 billion to $2 billion. If the Fed wants to put some oomph into QE2, it’s going to have to get the reserves out of the banks and into the economy. One way would be to raise the cost of not lending. Banks now earn 0.25 basis points on their reserves. (It wasn’t so long ago that paying interest on excess reserves was seen as a way to prevent an inflationary expansion of credit.) Reducing or eliminating the interest on reserves would, at the margin, entice banks to buy securities or make loans, expanding the money supply.

That was one of two other options -- aside from the one chosen yesterday -- that Fed chief Ben Bernanke laid out at his semi-annual monetary policy testimony last month. The second was tinkering with the assurances of "exceptionally low" rates for an "extended period." How the Fed can guarantee a more extended "extended period," both verbally and practically, when its outlook changes from one meeting to the next, is beyond me. Then again, I’m still trying to figure out where the Q is in QE2.

Quantitative Easing: "The Greatest Monetary Non-Event"

by The Pragmatic Capitalist

The topic of quantitative easing (QE) has rapidly become the most important discussion in the investment world. As deflation becomes the obvious risk and the economic recovery looks increasingly weak investors are again looking to the Fed to save their skin from a Japan style deflationary recession. The irony here is so thick you could choke on it, however, like some sort of sick masochist, investors continue to return to the trough of the Federal Reserve so they can gorge on half-truths and misguided policy responses.There is perhaps, no greater misunderstanding in the investment world today than the topic of quantitative easing. After all, it sounds so fancy, strange and complex. But in reality, it is quite a simple operation. JJ Lando a bond trader at Goldman Sachs has eloquently described QE:

“In QE, aside from its usual record keeping activities, the Fed converts overnight reserves into treasuries, forcing the private sector out of its savings and into cash. This is just a large-scale version of the coupon-passes it needed to do all along. Again, they force people out of treasuries and into cash and reserves.”

Some investors prefer to call it “money printing” or “stimulative monetary policy”. Both are misleading and the latter is particularly misleading in the current market environment. First of all, the Fed doesn’t actually “print” anything when it initiates its QE policy. The Fed simply electronically swaps an asset with the private sector. In most cases it swaps deposits with an interest bearing asset. They’re not “printing money” or dropping money from helicopters as many economists and pundits would have you believe. It is merely an asset swap.The theory behind QE is that the Fed can reduce interest rates via asset purchases (which supposedly creates demand for debt) while also strengthening the bank balance sheet (which entices them to lend). Unfortunately, we’ve lived thru this scenario before and history shows us that neither is actually true. Banks are never reserve constrained and a private sector that is deeply indebted will not likely be enticed to borrow regardless of the rate of interest. On the reserve argument the BIS explains in great detail why an increase in reserves will not increase borrowing:

“In fact, the level of reserves hardly figures in banks’ lending decisions. The amount of credit outstanding is determined by banks’ willingness to supply loans, based on perceived risk-return trade-offs, and by the demand for those loans.The aggregate availability of bank reserves does not constrain the expansion directly. The reason is simple: as explained in Section I, under scheme 1 – by far the most common – in order to avoid extreme volatility in the interest rate, central banks supply reserves as demanded by the system. From this perspective, a reserve requirement, depending on its remuneration, affects the cost of intermediation and that of loans, but does not constrain credit expansion quantitatively.

The main exogenous constraint on the expansion of credit is minimum capital requirements. By the same token, under scheme 2, an expansion of reserves in excess of any requirement does not give banks more resources to expand lending. It only changes the composition of liquid assets of the banking system. Given the very high substitutability between bank reserves and other government assets held for liquidity purposes, the impact can be marginal at best. This is true in both normal and also in stress conditions. Importantly, excess reserves do not represent idle resources nor should they be viewed as somehow undesired by banks (again, recall that our notion of excess refers to holdings above minimum requirements). When the opportunity cost of excess reserves is zero, either because they are remunerated at the policy rate or the latter reaches the zero lower bound, they simply represent a form of liquid asset for banks.”

The most glaring example of failed QE is in Japan in 2001. Richard Koo refers to this event as the “greatest monetary non-event”. In his book, The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics, Koo confirms what the BIS states above:“In reality, however, borrowers – not lenders, as argued by academic economists – were the primary bottleneck in Japan’s Great Recession. If there were many willing borrowers and few able lenders, the Bank of Japan, as the ultimate supplier of funds, would indeed have to do something. But when there are no borrowers the bank is powerless.”

In the same piece cited above, the BIS also uses the example of Japan to illustrate the weakness of QE. The following chart (Figure 1) shows that QE does not stimulate borrowing (and the history of continued economic weakness in Japan is coincidental):“A striking recent illustration of the tenuous link between excess reserves and bank lending is the experience during the Bank of Japan’s "quantitative easing" policy in 2001-2006. Despite significant expansions in excess reserve balances, and the associated increase in base money, during the zero-interest rate policy, lending in the Japanese banking system did not increase robustly.”

(Figure 1)

Koo goes a step further in describing the failure of QE to promote private sector recovery. His simple example is one I have used often:

“The central bank’s implementation of QE at a time of zero interest rates was similar to a shopkeeper who, unable to sell more than 100 apples a day at $100 each, tries stocking the shelves with 1,000 apples, and when that has no effect, adds another 1,000. As long as the price remains the same, there is no reason consumer behavior should change–sales will remain stuck at about 100 even if the shopkeeper puts 3,000 apples on display. This is essentially the story of QE, which not only failed to bring about economic recovery, but also failed to stop asset prices from falling well into 2003.”

Koo continues by emphasizing how ineffective monetary policy is during a balance sheet recession:“Even though QE failed to produce the expected results, the belief that monetary policy is always effective persists among economists in Japan and elsewhere. To these economists, QE did not fail: it simply was not tried hard enough. According to this view, if boosting excess reserves of commercial banks to $25 trillion has no effect, then we should try injecting $50 trillion, or $100 trillion”

After years of placing more apples on the shelves the Bank of Japan finally admitted that the policy had been a failure:“QE’s effect on raising aggregate demand and prices was often limited” (Ugai, 2006)

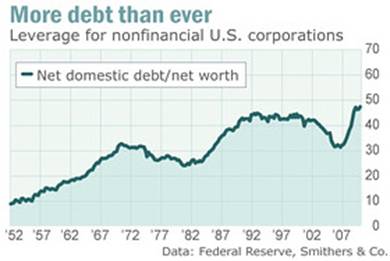

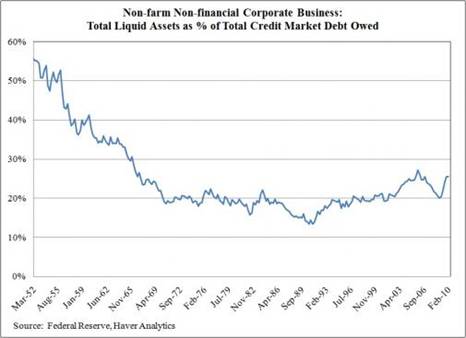

That all sounds too eerily familiar, doesn’t it? No, no – Mr. Bernanke hasn’t failed. He just hasn’t tried hard enough….But perhaps the reader believes Japan is different and not applicable. This is a reasonable objection. So why don’t we look at the evidence from the last round of QE here in the USA. Since Ben Bernanke initiated his great monetarist gaffe in 2008 there has been almost no sign of a sustainable private sector recovery. Mr. Bernanke’s new form of trickle down economics has surely fixed the banking sector (or at least bought some time), but the recovery ended there. It did not spread to Main Street. We would not even be having this discussion if we were in the midst of a private sector recovery. The surest evidence, however, is in the Fed’s own data. We can also look at the Fed’s recent Z1 to show that households remain hesitant to borrow (see Figure 2). Friday’s consumer credit data was yet another sign of contracting consumer credit and a lack of demand for borrowing. Despite the Fed’s already failed attempt at QE (see Figure 3) we are convinced that Mr. Bernanke just needs to throw a few more apples on the shelves. The historical evidence is clear – QE will do little to stimulate borrowing and help generate a private sector recovery.

(Figure 2)

(Figure 3)

In addition, there is one great irony in all of this misunderstanding. The hyperventilating hyperinflationists and those investors calling for inevitable US default are now clinging to this QE story as their inflation or default thesis crumbles before their very eyes. The new hyperinflationist theme has become a story of “if this, then this, then THIS!” – the ludicrous 3 step investment thesis that the economy will become so fragile that the government will pile on with more stimulus, which will worsen matters and force them to stimulate further which will then result in hyperinflation and/or default. Most investors have enough trouble predicting what the next event will be – connecting the dots two or three steps down the line is not only ill-advised, but is hardly even worthy of consideration….Let’s just call a spade a spade – the inflationistas have been wrong and the USA defaultistas have been horribly wrong.

What is equally interesting (in addition to the fact that QE is not economically stimulative) with regards to this whole debate is that this policy response in time of a balance sheet recession is not actually inflationary at all. With the government merely swapping assets they are not actually “printing” any new money. In fact, the government is now essentially stealing interest bearing assets from the private sector and replacing them with deposits. This might have made some sense when the credit markets were frozen and bank balance sheets were thought to be largely insolvent, but now that the banks are flush with excess reserves this policy response would in fact be deflationary - not inflationary. Why would we remove interest bearing assets from the private sector and replace them with deposits when history clearly shows that this will not stimulate borrowing?

All of this misconception has the market in a frenzy. Portfolio managers and day traders can’t wait to snatch up stocks on every dip in anticipation of what they believe is an equivalent to the March 9th 2009 low that was cemented by government intervention. As I have long predicted Ben & Co. have failed. If there is one thing that we know for certain over the last 24 months it is that Mr. Bernanke’s monetary policy has done very little to get the private sector back on its feet. This man failed to predict the crisis (was in fact oblivious to its potential), initiated the wrong trickle down policy response and yet now we turn to him to save us from a double dip and his Committee responds with more discussion of QE? Will we ever learn?

In describing the negligence of such monetary policy Richard Koo uses the analogy of a doctor who simply tells his patient to take more of the same medicine he originally prescribed:

“At the risk of belabouring the obvious, imagine a patient in the hospital who takes a drug prescribed by her doctor, but does not react as the doctor expected and, more importantly, does not get better. When she reports back to the doctor, he tells her to double the dosage. But this does not help either. So he orders her to take four times, eight times, and finally a hundred times the original dosage. All to no avail. Under these circumstances, any normal human being would come to the conclusion that the doctor’s original diagnosis was wrong, and that the patient suffered from a different disease. But today’s macroeconomics assumes that private sector firms are maximizing profits at all times, meaning that given a low enough interest rate, they should be willing to borrow money to invest.. In reality, however, borrowers – not lenders, as argued by academic economists – were the primary bottleneck in Japan’s Great Recession.”

Dr. Bernanke has misdiagnosed this illness one too many times. At what point does someone tell him to put the scalpel down and step away from the table before he does even greater harm?

Commodity spike queers the pitch for Bernanke's QE2

by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard - Telegraph

Don't be fooled: a food and oil price spike is not and cannot be inflationary in those advanced industrial economies where the credit system remains broken, the broad money supply is contracting, and fiscal policy is tightening by design or default.

It is deflationary, acting as a transfer tax to petro-powers and the agro-bloc. It saps demand from the rest of the economy. If recovery is already losing steam in the US, Japan, Italy, and France as the OECD's leading indicators suggest - or stalling altogether as some fear - the Eurasian wheat crisis will merely give them an extra shove over the edge. Agflation may indeed be a headache for China and India, where economies have over-heated and food is a big part of the inflation index. But the West is another story.

Yields on two-year US Treasury debt fell last week to 0.50pc, the lowest in history. Core US inflation is the lowest since the mid-1960s. US business inflation (pricing power) is at zero. Bank lending is flat and securitised consumer credit has collapsed from $900bn to $240bn in the last year. Hence the latest shock thriller - "Seven Faces of Peril" by James Bullard, ex-hawk from the St Louis Fed - who fears US is now just one accident away from a Japanese liquidity trap.

In Japan itself core CPI deflation has reached -1.5pc, the lowest since the great fiasco began 20 years ago. 10-year yields fell briefly below 1pc last week. Premier Naoto Kan has begun to talk of yet another stimulus package. "The time has come to examine whether it is necessary for us take some kind of action," he said. In a normal recovery, the US labour market would be firing on all cylinders at this stage. Yet the latest household jobs survey showed a net loss of 35,000 jobs in May, 301,000 in June, 159,000 in July.

The ratio of the working age population with jobs has fallen to 58.4, back where it was in the depths of recession. Over 1.2m people have dropped out the work force over the last three months, which is the only reason why the unemployment rate has not vaulted back into double digits. A record 41m Americans are on food stamps. This is unlike anything since the Second World War. It screams Japan, our L-shaped destiny. "Unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus has produced unprecedentedly weak recovery", said Albert Edwards from Societe Generale in his latest "Ice Age" missive. That stimulus is now fading fast before the private economy has clasped the baton.

After digesting Friday's jobs report, Goldman Sachs' chief economist, Jan Hatzius, thinks the Fed will abandon its exit strategy and relaunch QE this week, taking the first "baby step" of rolling over mortgage securities. Future asset purchases may be "at least $1 trillion". He is not alone. Every bank seems to be gearing up for QE2, even the inflation bulls at Barclays. The unthinkable is becoming consensus.

Into this deflationary maelstrom, we now have the extra curve ball of Russia's export ban on grains. There is a risk that this mini-crisis will escalate if Kazakhstan, Belarus, and Ukraine follow suit, and if the scorching drought lasts long enough to hit seeding for winter wheat next month. But remember, there was a global wheat glut until six weeks ago. Stocks are at a 23-year high. Prices are barely more than half the peak in 2008. The US grain harvest is bountiful; Australia, India, Argentina look healthy.

The Reuters CRB commodity index is no higher now than in April. Last week's commodity scare looks like an anaemic version of the blow-off seen in the summer of 2008. The chief risk is that central banks will panic yet again, seeing ghosts of a 1970s wage-price spiral that does not exist. In July 2008, Jean-Claude Trichet told Die Zeit that there was "a risk of inflation exploding". As we now know - and many predicted - eurozone inflation was about to fall off a cliff. But acting on this apercu, the European Central Bank raised rates. No matter that half Europe was already tipping into recession.

The Western banking system went into melt-down within weeks. The Fed was not much better. It issued an "inflation alarm" in August 2008. Dr Robert Hetzel of the Richmond Fed has written a candid post-mortem in "Monetary Policy In The 2008-2009 Recession", rebuking the Fed and ECB for over-reacting to inflacionista hysteria. They tightened into the crunch. For those wonkishly inclined, Dr Hetzel said their error was to view the enveloping crisis through a "credit" prism, missing the tectonic issue that the "natural rate of interest" had fallen below the Fed funds rate. Failure to diagnose the problem properly meant that Fed policy may have made matters worse. This is perhaps the best analysis I have ever read on what went wrong, yet it has received scant attention.

Do we have any assurance that central banks have learnt their lesson? Clearly not the ECB, judging from Mr Trichet's ill-judged article for the Financial Times two weeks ago: "Now it is Time for all to Tighten". Much of what he wrote is correct in as far as it goes. Public debt is out of control. Budget stimulus may start to backfire. We are at risk of a "non-linear" rupture should confidence suddenly snap in sovereign states. Yet he also suggested that half the world can copy the fiscal purges of Canada and Scandinavia in the 1990s, all at the same time, without setting off a collective downward spiral. He offered no glimmer of recognition that the fiscal squeeze must be offset by ultra-loose money. True to form, the ECB is now draining liquidity. Three-month Euribor has risen to the highest in over a year.

John Makin from the American Enterprise Institute described the Trichet argument that collective removal of fiscal thrust can be expansionary as "preposterous and dangerous". Mr Edwards called it "risible". Berkeley's arch-Keynesian Brad DeLong could only weep, saddened that everything learned over 70 years had been tossed aside in a total victory for 1931 liquidationism. "How did we lose the argument," he asked?

Unfortunately, such obscurantism is taking hold in the US as well. Alabama Senator Richard Shelby has blocked the appointment of MIT professor Peter Diamond to the Fed Board, ostensibly because he is a labour expert rather than a monetary economist but in reality because he is a dove in the ever-more bitter and polarised dispute over QE. The Senate has delayed confirmation of all three appointees for the board, who all happen to be doves and allies of Fed chairman Ben Bernanke. The Fed is in limbo until mid-September. So the regional hawks who so much misjudged matters in 2008 have unusual voting weight, and now they have a commodity spike as well to rationalise their Calvinist preferences.

Whatever Dr Bernanke wants to do this week - and I suspect he is eyeing the $5 trillion button lovingly - he cannot risk dissent from three Fed chiefs: one yes, two maybe, but not three. He faces a populist revolt from the Tea Party movement, with its adherents in Congress and the commentariat. And China simply hates QE, which may or may not be rational but cannot be ignored. Global markets have already priced in the next QE bail-out, banking the "Bernanke Put" as if it were a done deal. We will find out on Tuesday if life is really that simple.

Time to Re-think Milton Friedman?

by Rick Ackerman

Adding fuel to our recent discussion of deflation is the latest dispatch from Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, the only big-league journalist we know of who seems to have recognized all along that it is not inflation we should have feared, but deflation. "Don’t be fooled," he wrote recently in the U.K. Telegraph. "A food and oil price spike is not and cannot be inflationary in those advanced industrial economies where the credit system remains broken, the broad money supply is contracting, and fiscal policy is tightening by design or default."

Just so. And yet, there are still those who choose not to see the obvious. We still turn up posts in the Rick’s Picks forum that would have us believe that supposed price increases in day-to-day necessities represent a significant offset to a global financial implosion that has sucked hundreds of trillions of dollars worth of valuation from a global portfolio of leveraged financial assets.

This is hugely deflationary, as Evans-Pritchard notes, and in the case of higher grocery and energy costs, acts "as a transfer tax to petro-powers and the agro-bloc. It saps demand from the rest of the economy. If recovery is already losing steam in the US, Japan, Italy, and France as the OECD's leading indicators suggest -- or stalling altogether as some fear -- the Eurasian wheat crisis will merely give them an extra shove over the edge." This touches on a point we’ve made here before, and more than a few times – that price increases in necessities cannot create inflation if household incomes are stagnant.

Think about it: If the price of a gallon of gas were to rise to $10 a gallon tomorrow, we would simply have to cut back on the consumption of something less important. So where’s the inflation? Why the answer to this question continues to elude so many is mystifying. Perhaps those who remain skeptical of deflation’s power are renters who have not experienced the pain of having their mortgaged home decrease in value by 30 percent or more, as has occurred throughout the US.

Inflationist Delusion

Most persistent of the inflationists’ delusions is that the Federal Reserve can and will do "whatever it takes" to avoid deflation. But to believe that easing has not worked so far because the Fed has not eased enough is to imply that some further quantity of easing will do the trick. This kind of thinking is beyond dumb, but when it infects those on the left side of the Congressional aisle, it can be downright dangerous. Tea Partiers to the rescue?

They supposedly stand ready to put a lid on yet another round of stimulus, but at this point, probably, most Americans recognize that more stimulus, all of it with money to be borrowed by "the government" (i.e., by taxpayers) from future productivity, cannot achieve much of anything, save burying us even deeper in debt.

It manifestly has not stimulated inflation, as Evans-Pritchard notes with this short list of current data: "Yields on two-year US Treasury debt fell last week to 0.50 percent, the lowest in history. Core US inflation is the lowest since the mid-1960s. US business inflation (pricing power) is at zero. Bank lending is flat and securitised consumer credit has collapsed from $900 billion to $240 billion in the last year. Hence the latest shock thriller -- "Seven Faces of Peril" by James Bullard, ex-hawk from the St Louis Fed -- who fears that the United States is now just one accident away from a Japanese liquidity trap."

Armchair Monetarists

Readers, what do you think? We would be especially grateful to anyone who can drive a stake through the heart of the oft-repeated phrase "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." This phrase, demonstrated to have been worse than worthless for predictive purposes by actual monetary events of the last two decades, originated with economist Milton Friedman but has since been expropriated by armchair theoreticians, monetarists and others who have been more or less continuously –and wrongly -- predicting a horrific outbreak of CPI inflation since around 1991.

That is when the Fed eased massively (or so it seemed, for those times) to power us out of recession and the S&L crisis. Friedman, like virtually all of the monetarists his theories had empowered, might have been fooled the first time around, when the universally predicted inflationary spiral failed to materialize thereafter. But we wonder what he would think now, had he been able to witness how the cosmic-size stimulus of the last few years failed to produce any inflation whatsoever.

Indeed, recent events have demonstrated that all of the credit-money the Fed is capable of ginning up will not produce even an iota of inflation if borrowers and lenders do not take that money and run with it. Some might say the easing associated with the 1990-91 recession did in fact produce inflation, albeit of equity shares rather than consumer goods.

They would also note that subsequent periods of loose money caused massive inflation of financial assets and real estate. This line of argument is disingenuous, however, since, even as these inflationary events were unfolding, low CPI inflation was explicitly cited by policymakers as justification for further easing. Moreover, Alan Greenspan, to the eternal disgrace of an already Dismal Science, regarded all non-CPI inflation not only as benign but, in the case of home prices, as wealth-producing.

We doubt that Friedman would have made so egregious a mistake. Dare we imagine that if he were still alive, that, seeing the catastrophe that Fed manipulation of interest rates had wrought, he’d be more willing to let market forces alone, rather than the central bank, determine when the supply and demand for money were in equilibrium?

Fed Will Meet With Concerns on Deflation Rising

by Sewell Chan - New York Times

The Federal Reserve will meet on Tuesday faced with a pivotal decision about whether to abandon its presumption that the economy is gradually picking up steam and begin to consider new steps to keep the recovery from sputtering out. A string of developments, including the weak jobs report last Friday, has altered the sentiment within the central bank, leading Fed policy makers to stop worrying for the moment about the increasingly remote prospect of inflation. Instead, they are increasingly focused on the potential for the economy to slip into a deflationary spiral of declining demand, prices and wages.

Economists, including former Fed officials, say the central bank’s interest rate policy committee is likely, at the least, to acknowledge the slowdown in the recovery, and to discuss steps like reinvesting the proceeds from its huge mortgage-bond portfolio, which could help the economy by keeping more money in circulation. Not since 2003 has the prospect of deflation been taken so seriously at the Fed, and not since the 2008 financial crisis have the markets been looking so closely to it for guidance. With Congress unwilling to embark on substantial new stimulus spending, the Fed has the only tools likely to be employed anytime soon in response to the economic warning signs.

The Fed’s chairman, Ben S. Bernanke, and other officials believe that the Fed, having lowered interest rates all the way to zero in 2008, still has the ability to avoid deflation. But they are also concerned that any new dose of monetary medicine could carry unintended side effects, making it harder to normalize policy in the future. Complicating matters, a vocal minority of Fed officials is skeptical that deflation — a spiral of falling wages and prices, which Japan’s economy has experienced since the 1990s — is even a worry. "The outcome of this meeting is more uncertain than in any in at least the last year," said Laurence H. Meyer, a former Fed governor.

At the Fed’s last meeting, in June, the prospect of deflation was discussed for the first time this year. Alan Greenspan, the Fed chairman for 18 years until he retired in 2006, said Friday that the economic outlook had darkened. "It strikes me as a pause in the recovery, but a pause in this type of recovery feels like a quasi-recession," he said. He added: "At this particular moment, disinflationary pressures are paramount. They will not last indefinitely."

Mr. Greenspan said there had been "some evidence of a pickup in inflation" until the Greek debt crisis took hold in the spring. But the resulting uncertainty drove down long-term interest rates — the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note fell to 2.82 percent on Friday, the lowest level since April 2009, and barely budged Monday — in a reflection of what Mr. Greenspan called continuing problems in the financial markets. Mr. Greenspan declined to make recommendations or predictions for Fed policy, but on Wall Street, there is already talk that the Fed could begin a new round of quantitative easing — buying financial assets to hold down long-term interest rates and increase the supply of money.

Jan Hatzius, chief United States economist for Goldman Sachs, predicted on Friday that the Fed would begin a new round of asset purchases — which could include at least $1 trillion worth of Treasury securities — late this year or early next year. He revised down his forecast for the growth of gross domestic product in 2011 to 1.9 percent from 2.4 percent. He also predicted that unemployment would hit 10 percent in the second quarter of next year.

Among the voting members of the central bank’s policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee this year, the presidents of the Fed’s Boston and St. Louis district banks have warned recently about the threat of deflation, while the Kansas City bank president is known for his view that inflation, the Fed’s traditional enemy, remains the greatest threat. But it is Mr. Bernanke who holds the most say over the outcome.

Randall S. Kroszner, a former Fed governor, said the committee was certain to alter its outlook in its statement on Tuesday. "I think the language will broadly change to acknowledge the moderation in the pace of the recovery," he said. Mr. Kroszner said it seemed increasingly likely that the Fed could announce that it would reinvest the cash it receives as the mortgage bonds it holds mature, rather than letting its balance sheet gradually shrink over time.

In March, the Fed completed its purchase of $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities. A decision to reinvest the bond proceeds in other mortgage-related securities, or in Treasuries, would be largely symbolic but carry great weight, as it would signal concern about the economy, and also make clear that an "exit strategy" from easy monetary policy was not imminent. The Fed might also be poised to discuss two other options: lowering the interest rate it pays on the roughly $1 trillion in reserves that banks are keeping at the Fed in excess of what they are required to, and altering the "extended period" language it has been using to describe how long short-term interest rates will remain at "exceptionally low" levels.

Frederic S. Mishkin, another former Fed governor, said that most recoveries hit speed bumps, and that economic indicators contained considerable statistical "noise." He said the Fed would be prudent not to overreact. "It’s not clear the Fed needs to ease at this point," Mr. Mishkin said. "If the recovery gets back on track they are still going to have to worry about an exit strategy. Quantitative easing is not a trivial matter. The expansion of the balance sheet leads to many complications for the Federal Reserve." But Mr. Meyer, the former Fed govenor, said the committee should take into account not just the probability of various outcomes, but the potential damage associated with each of them.

"Because the cost of a slowdown in growth is so dramatic relative to that of higher inflation, they should follow the risk-management strategy that Greenspan espoused during the last deflation scare," he said. During that period, in 2002-3, the Fed kept interest rates low, as the economy recovered from the 2001 recession, to guard against deflation. Those fears did not come to pass. But some now say the Fed kept rates too low for too long, feeding the housing bubble. "It is by no means a slam dunk," Mr. Meyer said of the Fed’s decision.

Fed could 'climb aboard QE2' to boost stalled US recovery

by James Quinn - Telegraph

Just days after the US annualised growth rate was found to have slowed from 3.7pc in the first quarter to 2.4pc in the second, and amid continuing concerns about the strength of the rebound in the housing market, for Geithner to write "we are coming back" was seen as ill-judged. The Atlantic, the weekly US news magazine, called the piece "Tim Geithner's pathetic case for optimism" while one of the New York Times' own readers – a Susan McGregor of Rhode Island – wrote in to say she believed that rather than recovery "a temporary remission" would have been "more accurate".

After last Friday's non-farm payroll figures – showing the US economy lost 131,000 jobs in July, the second consecutive monthly fall – and Goldman Sachs' subsequent 2011 growth downgrade, Geithner's comments looked even more out of step. Just how out of step will be revealed at 7.15pm on Tuesday, when the Federal Reserve's Open Markets Committee gives its latest prognosis on the state of the US economy.

In what will be one of the most closely watched meetings in some time, FOMC is likely to hold rates at 0pc-0.25pc – for the 17th time in a row. But it is not for a potential rate change that investors will be watching. Instead, as Goldman Sachs' Ed McKelvey coyly put it, it is whether the Fed will be "climbing aboard QE2 to avoid a double dip?" The QE2 in question is not the ocean liner – but a second bout of quantitative easing designed to kick-start the economy to prevent it sinking back into another period of negative growth.

Paul Sheard, Nomura's chief global economist, was the first Wall Street economist to argue that Ben Bernanke, the Fed's chairman, and his nine FOMC colleagues should take some form of affirmative action to get the US recovery back on track. Sheard, in a note published a week ago, argued that the most likely action is for the Fed to "at least stop the passive contraction of its balance sheet". His comments followed those of James Bullard, president of the St Louis Federal Reserve and a voting member of the FOMC, who said the central bank needs some form of quantitative easing plan.

Of course, as McKelvey points out, the Fed has been here before. The first round of quantitative easing saw the Fed buy $1.7 trillion (£1.1 trillion) of mortgage-related bonds and US Treasuries to resuscitate the economy. Until now, the process was largely thought to have worked, allowing the Fed to slowly rein in its activities – reducing its balance sheet from the $2.3 trillion it reached at its peak. But economists are now questioning whether the Fed moved too soon. Speaking before the US Congress last month, Bernanke detailed three ways in which the central bank might step in if needed.

The first was as outlined by Sheard, the second was restarting the asset purchase programme, while the third – the weakest of all perhaps – would be to change the language in the FOMC's much-analysed statement after Tuesday's or subsequent meetings to point out that deflation will not be tolerated. David Rosenberg, chief economist at Gluskin Sheff and one of the earliest economists to make the deflation "call", noted that "there is growing chatter that the Fed is once again going to come to the rescue".

Indeed the rumour mill includes some form of mortgage-relief scheme to help borrowers suffering from negative equity, while there is also talk of the Fed detailing a new $2 trillion easing programme. There is also talk in Washington of the Fed recycling money redeemed from its earlier easing programme into a new series of asset purchases. But, despite of the flurry of recent negative economic data, not everyone on Wall Street believes it is time for the Fed to act. Simon Hayes, economist at Barclays Capital, says he has "detected no change" in the Fed's tone in recent weeks, while economist Tom Higgins at Payden & Rygel argues that a double-dip recession remains a "low probability" and as a result the Fed is unlikely to act to "boost economic activity".

Goldman's McKelvey disagrees, however, predicting the Fed will "embrace a new asset purchase programme" if not on Tuesday then at the turn of the year. It will have to be at least $1 trillion to "have a meaningful effect", he claims. Amongst all this economic debate about the status of the US recovery, it is worth noting that the US National Bureau of Economic Research – the independent arbiter of US business cycles – has yet to declare an end to the 2007-09 recession, meaning that whatever the Fed chooses to do, the US is not quite ready hang up the "Welcome to the recovery" bunting just yet.

The Worrying Numbers Behind Underwater Homeowners

by Charles Hugh Smith - Daily Finance

By the end of the first quarter of 2010, the number of mortgaged residential properties with negative equity had declined slightly to 11.2 million, down from 11.3 million at the end of 2009, according to a report issued by real estate analytics firm CoreLogic. The report includes data through the first quarter, and is CoreLogic's most recent available study.

The bad news: Those 11.2 million loans make up roughly 24% of all U.S. mortgages. Add the 2.3 million borrowers who are close to slipping underwater (those with less than 5% equity), and the numbers rise to 13.5 million -- 28% of mortgages.

This aligns with other industry estimates. Earlier this year, Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's Economy.com, estimated that roughly 15 million American homeowners owe the bank more than their home is worth. (Note: On Aug. 9, Zillow Real Estate Market Reports said the percentage of single-family homes with negative-equity mortgages fell to 21.5% in the second quarter, from 23.3% in the first quarter, due mostly to higher foreclosures in the period.)

Calculating how many households are underwater, how far underwater they are and how many others are at risk of sliding into negative equity should housing values decline further is critical to forecasting future foreclosures, a recovery in housing values and the financial health of U.S. households.

Negative Equity Boosts Foreclosure

The data confirms the common-sense expectation that there's a direct correlation between negative equity and foreclosures: As the number of homeowners who are underwater rises, so do foreclosures.

Many homes are worth only half of their mortgages. There are 4.1 million homeowners with more than 50% negative equity and another 5 million homeowners with 20% to 50% negative equity.

So the majority of the 11.2 million properties with negative equity (9.1 million) are deeply underwater and are thus unlikely to be made whole by modest increases in home prices. That makes further increases in foreclosures likely, and so it's unsurprising that Economy.com expects that this year's foreclosures will swell to 2.4 million.

How Many Homes Could End Up Underwater?

If prices decline into 2011, as some analysts project, how many homes could slip into negative equity?

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of 2008, 51 million households had a mortgage, 24 million owned homes free and clear (no mortgage) and about 37 million households rented their homes.

In 2008 and 2009, foreclosures dissolved roughly 4 million mortgages, reducing the total number of outstanding mortgages to around 47 million. The total number of U.S. home-owning households stand at about 71 million.

The data presented by CoreLogic backs up these conclusions:

- The highest percentage of homes with negative equity are concentrated in the states that experienced the most extreme price increases and the subsequent severe declines in valuations: Nevada, Arizona, Florida and California.

- Though the media focuses on the "bubble" states, many other states also have high rates of negative equity: Over 20% of homeowners in Virginia, for example, are underwater, and an additional 5.7% are in near-negative equity territory.

- Properties with more than one mortgage -- those with second mortgages or home equity lines of credit (HELOC) on top of first mortgages -- were twice as likely to be underwater than those with only a first mortgage (38% vs. 19%).

What is surprising is how few homes have conventional 30-year mortgages that require a down payment. An analysis I performed in 2007 found that only 12 million of the roughly 48 million homes with mortgages had only a conventional fixed 30 year mortgage and no additional liens.

So only 25% of all homes with mortgages had what was once the only loan available, the conventional 30 year fixed mortgage supported by a 20% cash down payment.

The other 75% of mortgaged homes had loans that greatly increased the risk of falling into negative equity or delinquency:

- Low-down-payment mortgages -- as low as 3% for Federal Housing Administration (FHA)-backed loans. The FHA recently reported that fully 24% of its vast portfolio were "problem loans" -- seriously delinquent or in default.

- "Exotic" subprime loans

- Adjustable-rate mortgages that can reset to much higher payments after a few years

- Two mortgages -- a first mortgage and a "junior lien" such as a second mortgage or a home equity line of credit (HELOC)

All this suggests that only 25% of mortgages -- those with 30 year fixed-rate mortgages -- are at low risk of negative equity. The remaining 75% -- mortgage holders at higher risk of negative equity or already underwater -- number about 35 million households and make up around half of total home-owning households (71 million). Of the 50% of homeowners with risky loans, some 11 million are already underwater.

The Equity Gap

According to the latest Federal Reserve Flow of Funds report, there was $10.24 trillion in U.S. residential mortgages and $16.5 trillion in total home equity.

Since there are about 47 million outstanding mortgages, and 24 millions homes owned free and clear (no mortgage), then we can calculate that free-and-clear owners hold about a third of the $16.5 trillion in home equity -- roughly $5.3 trillion. That leaves about $1.2 trillion in equity spread amongst the 47 million homes with mortgages.

Given the likelihood that those with a conventional fixed-rate mortgage are most likely to have substantial equity, then it follows that this $1.2 trillion in equity is concentrated in the 12 million homes with conventional mortgages.

Subtract the 11 million homeowners who are underwater and have no equity, and that suggests that the remaining 25 million homeowners with exotic, adjustable or multiple mortgages have relatively little equity.

A recent analysis of long-term U.S. real estate data concluded that over time, the nation's housing equity (collateral) can sustain a mortgage load of approximately 40% of total equity. Thus in 1990, $6 trillion of housing collateral supported $2.5 trillion of mortgages, and the $23 trillion of housing collateral in 2006 sustained $10 trillion of mortgages.

Since then, equity has fallen $7 trillion to $16.5 trillion, but mortgages have barely declined -- they remain at $10.24 trillion. To revert to the long-term trend, mortgages will have to decline by $4 trillion to about $6 trillion.

The conclusion: Never before have American homeowners with mortgages held such a thin slice of equity, and never before have so many homeowners been at risk of negative equity. Predicting accurately how many homeowners end up underwater is impossible, as the future of home prices is unknown. But anyone claiming that the number of underwater homes can't rise further is on thin ice.

Fannie Mae Seeks $1.5 Billion in Aid

by Shanthi Venkataraman - The Street

Fannie Mae requested an additional $1.5 billion of funds from the U.S. Treasury to meet its net-worth deficit after it reported a loss for the second quarter. That would raise Fannie Mae's total bailout from the Treasury to $86.1 billion, including the $8.4 billion worth of funding it received to plug its deficit in the first quarter. The country's biggest residential mortgage financier, Fannie Mae reported a net loss of $3.1 billion or 55 cents per share for the second quarter, lower than its loss in the year-ago quarter of $15.1 billion or $2.67 per share. The Fannie Mae loss figure includes $1.9 billion of dividends paid on its senior preferred stock held by Treasury.

Revenue rose to $4.5 billion, 13% higher than the year-ago quarter and 49% higher than the first quarter of 2010 for Fannie Mae. Fannie Mae reduced its losses on the back of a decrease in the rate of seriously delinquent loans in the second quarter to 4.9% from 5.7% in the first quarter. Credit-related expenses declined 75% to $4.85 billion from the year-ago quarter. The company expects credit-related expenses to remain elevated through 2010.

The government took control of the government-sponsored mortgage financiers, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, in 2008 after toxic mortgages threatened to swallow their capital reserves. The agencies have received about $145 billion in bailout money since then. While most banks have managed to repay bailout funds and even ratchet up profits, Fannie Mae continues to turn in losses -- and the likelihood of taxpayers getting back their full investments has become increasingly dim.

So far the government has been unable to figure out a way to resolve the problems of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac without rocking the housing market. Even as their losses mount, both the agencies, which control over half the U.S. residential market, have continued to guarantee and insure loans as well as re-modify them for borrowers struggling to pay off their debt. That has helped prop the housing market and send mortgage rates to record lows.

During the first half of 2010, Fannie Mae purchased or guaranteed $423 billion in loans, which includes approximately $170 billion in delinquent loans the company purchased from its single-family mortgage-backed securities trusts. Since January 2009, Fannie Mae has helped finance 4.1 million single-family loans and 487,000 multi-family units. In the second quarter, Fannie Mae completed home retention workouts (modifications, repayment plans and forbearances) for more than 132,000 loans, 26% higher than the number of those completed in the first quarter.

Fannie Mae estimates that home prices improved 2.2% in the second quarter. It expects housing prices to decline slightly for the balance of 2010 and 2011 before stabilizing and that home sales will be flat for 2010. "Across our industry, we are seeing a more realistic approach to housing and lending that bodes well for the future," said CEO Mike Williams. "At Fannie Mae, we are committed to maintaining appropriate standards while also supporting affordable housing for low- and middle-income families. We will also continue to support a variety of programs to reach borrowers who need help, so that whenever possible, they can avoid foreclosure and stay in their homes," he said. The penny stock shed nearly 9% on Thursday to close at 36 cents.

Freddie Mac Swings to Loss, Seeks More Aid

by Nick Timiraos - Wall Street Journal

Freddie Mac reported a second-quarter net loss of $4.7 billion and asked the U.S. Treasury to provide a $1.8 billion infusion, raising the government's tab for its rescue of the mortgage-finance company to $63.1 billion. The second-quarter loss, the 11th in the last 12 quarters, compared with a year-earlier net profit of $300 million. Credit losses at Freddie remained high, at $5 billion, though that was down slightly from past quarters as borrowers fell behind on their mortgages at a slower pace and as home prices improved.

But low interest rates led to a $3.8 billion loss on derivatives and the company posted a $900 million charge due to an error in how it had been accounting for its backlog of delinquent loans. Freddie Mac and its larger cousin, Fannie Mae, continue to bleed money largely because of loans that were made as the housing boom turned to bust. As loans turn delinquent, the companies must set aside more money for future losses that they could take as homes sell through foreclosure.

Analysts are split over how soon the companies might stop losing money. In recent months, falling delinquencies and home-price stabilization have led to some signs that the companies' worst losses have passed. "Maybe they are seeing some light at the end of the tunnel. Whether it's sunlight or something else, that's the argument," says Brian Harris, senior vice president at Moody's Investors Service.

At Fannie, the volume of nonperforming loans fell during the second quarter by nearly 3% to $217 billion, though that was still up 22% from a year ago. But nonperforming-loan volumes at Freddie continued to rise during the second quarter to $118 billion, up 2% for the quarter and 36% from a year earlier. So far, Freddie has reserved about 32 cents for every dollar in nonperforming assets, while Fannie has reserved about 27 cents. That makes the companies "massively underreserved," says Paul Miller, an analyst with FBR Capital Markets. "There's a lot more losses coming our way with these companies."