"Wife of Texas tenant farmer. The wide lands of the Texas Panhandle are typically operated by white tenant farmers, i.e., those who possess teams and tools and some managerial capacity"

Ilargi: After another annual gathering of the empty headed at Jackson Hole, replete with economists looking at each other to once again confirm what deep down they know not to be true, in their desperate attempts to convince themselves and others that the trade they ply is based in science instead of simple belief and wishful thinking, we come away yet another time realizing that these folks are entirely useless when it comes to reorganizing our economies in any meaningful way, at least one that would benefit society as a whole, not just its political and financial elites.

Perhaps economics should be taught in seminaries and madrasses, so someone can step up and ask the pope to beatify Milton Friedman. Speaking of which, Ben Bernanke held another one of his Delphic Fed-speak talks, devoid of any substance, and the markets went up. When it comes to solving the problems caused by their own baseless ideas about how things work, they have nothing. But when it comes to lulling the gullible into complacency, then yes, it all still works like a charm.

Still, it never ceases to amaze that empty hot air evokes such exuberance, if even just for one day. Certainly when on the same day that Bernanke spoke, the US Commerce Department's Bureau of Economic Analysis adjusted its 2nd quarter 2010 GDP number downward 33% (!).

Sure, Bernanke has said he will do everything in his power to prevent further economic mayhem, and that he still has tools left to do it with. But then, he has said the exact same thing numerous times over the past few years, and look where we are: an at best anemic GDP growth, unemployment at (U3) 9.5%-(U6) 17.5%, homes sales down the drain, an expected 4 million foreclosures in 2010 even as lenders strongly hold off on repossessing homes, in short: not a pretty picture at all. The Federal Reserve epitomizes the Receding Horizons of finance revisited: it's always: next time, we’ll bring the big guns!

The Fed will likely buy more Treasuries and perhaps even dabble further into wobbly securities. Which may be nice for financial institutions, but does nothing for society as a whole. On the contrary, that very society's badly needed money is used to purchase the paper, just so banks and lenders may live to see another day. The USA has its priorities upside down and scrambled up in many fields these days, but arguably nowhere more so than in its economy and the politics that shape it.

But I wanted to talk a bit more about the revised Bureau of Economic Analysis GDP numbers. A 33% revision within one month (from 2.4% to 1.6% growth) can hardly be ranked as "margin of error", can it? Makes you wonder what they base their valuations on. Makes you wonder, too, what happens if an airline pilot misses his runway by 33%.

By the way, consensus has it that the US needs 2.5% GDP growth just in order not to see unemployment rise even further. Keep that in mind. And count your blessings. Equally funny is it to see that media, economists and politicians, to a (wo)man, stop dead in their prediction tracks at "slow growth", or something along those lines; nobody dare mention negative growth. After all, we have a recovery, right, even if it's slowing a tad?!

Which kind of inevitably brings me back, once more, and at the risk of boring you, to the Consumer Metrics Institute and the interpretation of their data by Doug Short. Apologies in advance, but I do think these numbers are that important.

Yes, there are differences between the BEA and CMI data. As pointed out before, the CMI tracks only the 70% of US GDP driven by consumers. No government, except for those expenditures that directly benefit the consumer. Think the $8000 tax credit for home buyers, or the Cash for Clunkers program (not sure about the Bush tax cuts). But, as is abundantly evident, the CMI follows the BEA very closely, if you interpret the data in the right way.

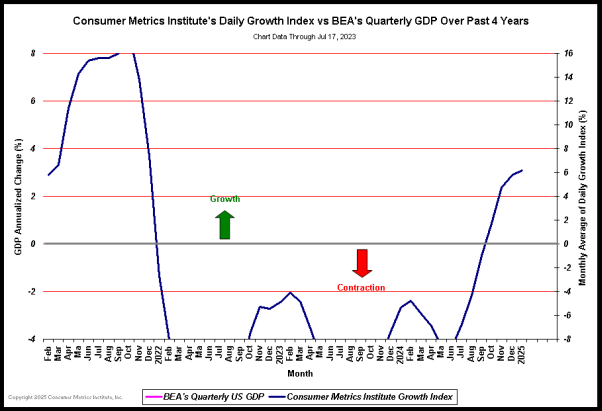

Here’s the original graph again, updated for Friday's numbers:

As discussed before, there are a number of issues with this graph that make it less "strong" than it could, and arguably should, be. First, the BEA GDP stats cover April-June 2010, but it's almost September now. The CMI numbers are updated daily, they don't "look back" the way the BEA ones do. The disparity is at least one quarter "wide", since Friday's BEA 2.4% to 1.6% growth correction includes data dating back to early April, close to 5 months ago.

Therefore, in order to get a clear picture, you have to move one of them forward and the other one back. I dove into my left-over long-ago Photoshop tricks to redo the graph, and chose to leave the BEA GDP number where it was, and move the CMI data forward by one quarter. The idea behind this move is that, seeing the -delayed- correlation between the two, the CMI stats -arguably- take on the quality of predicting where the GDP stats will go, as you will see. The first step - leaving out the S&P 500- looks like this:

Then there's the S&P 500 numbers that Doug Short incorporated into his graph. Since these, if you follow the sequence of peaks and troughs in the first graph, evidently lag the GDP numbers by about one quarter, you need to push them about back that amount, i.e. in the opposite direction from the CMI data, thereby establishing a two-quarter difference between the two. Which leads to this graph:

Now they peak and trough at the same "moment". Granted, it's not a perfect correlation. But then again, I would argue that at the same time it’s far too good to dismiss offhand.

Let's try this: permit the CMI a two year run-up time, and let's start at January 1 2007. Which would look something like this:

Now the correlation is very strong, apart perhaps from an initial "irrational exuberance" from the S&P, presumably coming out of the last gasps of very cheap credit in the pre-Lehman collapse period. The S&P is a bit of the odd duck out, but it's still not too far off.

All this serves, as I noted above, to point out to what extent the CMI data may serve as potential predictors for the second half of 2010, of which, in case you forgot, 2 months have already passed. For Q1 2010, the CMI seems to run alongside with the BEA data pretty closely. Even as, and this becomes clearer in Q2, BEA GDP numbers come in one quarter "blocks", i.e. they depict the average over 3 months.

In Q2, this "closeness" is no longer there. Friday's revision, as stated, brought BEA GDP numbers down from 2.4% to 1.6% growth , whereas CMI data seem to indicate an average contraction of about -1%. Looking forward towards Q3, of which we’ve already spent 2/3, mind you, CMI data point to a -2% contraction. For Q4, we're looking at some -4.5%. And there doesn't seem to be a lot of positive movement that could stop a further downfall.

Adding these to the graph gives us this:

These are alarming numbers. That is, if you wish to see them: you are, of course free to believe what the government says.

The one big caveat, again, consists of the fact that the CMI doesn't track government expenditures, other than those that enter the economy at large directly. But that in turn means that Washington would have to make up for a -5-6% contraction in the 70% of the economy led by consumers, as well as keeping its own spending habits "neutral".

Here's thinking no such thing will materialize. Sure, Bernanke can buy trillions of dollars of Treasuries, but hardly any of that "spending" will reach the real economy, and certainly not in time to balance out the deep dark abyss presented by the CMI data. We won't receive revised BEA Q3 GDP numbers until late November, of course, but does that really matter?

Provided we take the CMi data seriously, the downfall is already locked in. Barring, perhaps, a direct $1 trillion give-away to American citizens. But that will not happen, there'll be no free money in the USA, except for bankers. And besides, even if there would be, in the present economical climate most Americans would just sit on that money and hock it, and there’d be no stimulus to speak of.

While I was Photoshopping, I did notice another neat little thing. If I lower the CMI graph a little (and nudge it a bit more to the right), it matches the BEA peaks and troughs even better. But then, that also brings the contraction down even more, below -6%. Don't let's go there, shall we? It's bad enough as it is.

To summarize: we will either find out that Ben Bernanke never had any big guns or tools, and the US economy will scratch the gutter -using the heads of the poor to do so-, or the Fed will come out cannons ablazing, but then they'll still have to use taxpayer money. They, and you, can't win this one, unless truly spectacular growth rates will emerge out of the blue, preferably no later than tomorrow morning. Which are impossible without huge rises in homes sales and job creation, neither of which are even beyond the horizon.

How accurate the CMI numbers, and their "predictive value", are can best be determined by looking at how well they've matched the BEA data over the past 40 months. Watching the two, I'd say: ignore them at your own peril. Remember: the 91-day trailing CMI Growth Index started the week at -5.06%, and finished Friday at -5.43%.

What do you think: women and children first?!

Inside the BEA's Latest GDP Numbers

by Consumer Metrics Institute

On August 27, the Bureau of Economic Analysis ("BEA") of the U.S. Department of Commerce revised downward their previously reported measurement of the U.S. Economy's growth for the 2nd quarter of 2010. The newly reported annualized growth rate is 1.6%, down from a 2.4% rate published just 28 days earlier -- a 33% downward revision of the growth rate in four weeks. The BEA now reports that the past three quarters of annualized GDP growth have been (in sequence from Q4-2009) 5.0%, 3.7% and 1.6% -- with the rate dropping 2.1% from Q1-2010 to Q2-2010, the sharpest decline in the annualized growth rate since the summer of 2008.

(Click on chart for fuller resolution)

Another quarter like the second quarter would put the entire economy into governmentally admitted contraction, despite the nearly $649 billion in stimulus spent or in the process of being spent. With only about $143 billion remaining between unstarted projects and unclaimed tax cuts, it is hard to see how the residual stimulus funds will reverse the trends obvious in the above chart.

Another set of numbers within the BEA report addresses a more natural part of any economic cycle: the tendency of factories and distribution channels to over-correct inventory levels during times of economic expansion or contraction. Over recent quarters factories had been building inventory levels in anticipation of a sharp and sustained recovery from the "Great Recession". During the past three quarters that inventory building added 2.83%, 2.64% and 0.63% to the published GDP numbers. Notice the drop between the last two numbers; that more than 2% drop in that inventory component from Q1-2010 to Q2-2010 mirrors the reported 2.1% decline in the overall GDP growth rate -- indicating that the cutback in inventory build-ups alone can explain most of the quarterly drop in the published growth rate. During the "Great Recession" of 2008 the inventory adjustments swung sharply negative, lowering the published GDP by as much as 2.31% during the fourth quarter of 2008. It is clear from the 2% drop between Q1-2010 and Q2-2010 that the current cycle of inventory building has collapsed. If the BEA's (often late arriving) inventory data should swing negative (as it did in the third quarter of 2007), the published numbers for the third quarter 2010 GDP could well be negative.

As the chart above shows, our measurements of on-line consumer demand for discretionary durable goods are substantially more negative than the BEA's published GDP for the full economy. Our year-over-year Daily Growth Index peaked in August, 2009 and started net year-over-year contraction on January 15, 2010. Our numbers differ from the BEA's for a number of reasons (more fully explained in several of our FAQs), but suffice it to say that:

► The only portions of the $649 billion in spent stimulus reflected in our data are the consumer packages (such as "Cash for Clunkers" and the Housing Tax Credits), which both contributed to our August 2009 peak and have now lapsed;

► Our consumers and the types of purchases we track them buying are leading and highly volatile -- which is precisely why we track them.

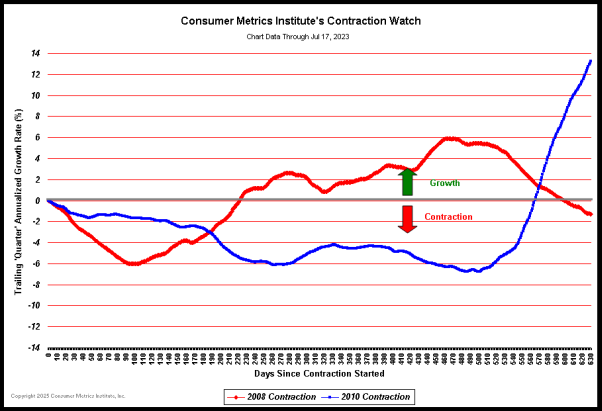

We constructed our indexes to provide an advanced look at how an economic cycle is progressing. The best tool we have for that is our "Contraction Watch", which overlays graphically the day-by-day progression of the current 2010 contraction onto the "Great Recession" of 2008:

(Click on chart for fuller resolution)

In the above chart the two contractions are aligned on the left margin at the first day during each event that our Daily Growth Index went negative, and they progress day-by-day to the right tracing out the daily rate of contraction.

The key take-away from our "Contraction Watch" is that the profile of this contraction episode is different, principally (at this stage) in the longevity of the event. The "Great Recession" had a contraction duration of 221 days. The current 2010 contraction event has already lasted longer, and we cannot even begin to guess when it might end. Several months ago we had commented that the shape of the current 2010 contraction episode was developing in a relatively mild but persistent manner -- likening it to a "walking pneumonia", in sharp contrast to 2008's "call 911" severity. That analogy is no longer valid.

If we realize that the total economic pain inflicted by a contraction event is a function of both the daily contraction rate and the duration of the event, then the best measure of that pain is simply the area in the above chart between each of the curves and the gray "zero" axis. The "Great Recession" of 2008 accumulated slightly over 793 negative-percent-contraction-days. Within a week, current 2010 event will be over 500, and even should it suddenly reverse and trace out a 2008-like recovery arc, the total pain will be very near 2008's total. Given our data on how political "Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt" negatively impacted consumer spending on discretionary durable goods in 2008, we anticipate no miraculous upsurge in U.S. consumer discretionary spending before November 2.

Barring some sudden reversal in consumer attitudes and habits, the 2010 economic slowdown will be longer and at least as painful as the one experienced in 2008. Furthermore, the shape of this contraction event indicates that it is probably not an independent "double dip", but simply a continuation of the "Great Recession" of 2008 after a few quarters of now lapsed consumer stimulation.

U.S. economic growth slows to 1.6% in second quarter

by Steve Goldstein - MarketWatch

Imports lead to sharp downward revision to GDP

U.S. economic growth slowed to 1.6% in the second quarter, the Commerce Department said Friday, two-thirds the rate that the agency had initially projected for the April-through-June period as imports surged. The figures more broadly paint a picture of a $14.58 trillion economy led by business investment, one that data on more recent activity suggest is struggling to grow.

Gross domestic product, reflecting the inflation-adjusted, seasonally adjusted value of all goods and services produced in the U.S., slowed from the 3.7% annualized pace in the first quarter, the Commerce Department's data showed. Final sales to domestic purchasers -- which include consumers, businesses and the government -- rose 4.3%. The sharply downward GDP revision from the 2.4% growth initially pegged was largely expected after the release of June inventories and imports reports, which were not available for the first estimate released on July 30.

Economists polled by MarketWatch, however, had expected an even worse figure showing of 1.3% growth in the second quarter. As expectations of growth grew increasingly pessimistic in recent days, U.S. stocks started the session modestly higher, and after an initial downturn following a speech from Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and a revenue warning from Intel, turned higher again.

Wall Street appears to have been caught off-guard by an upward revision to electricity and natural-gas usage figures, which led to an increase in real personal consumption to 2% from the 1.6% initially projected. A simple explanation, offered by Bank of America Merrill Lynch's Neil Dutta: households ran their air conditioners longer because of warmer-than-average temperature.

The quarter was marked by a big jump in business spending as companies replenished equipment they hadn't replaced during the recession, with business fixed investment rising 17.6%. "We can look at the revised second quarter numbers and recognize that the economy was essentially driven by business spending on equipment and software," said Steve Blitz, senior economist at Majestic Research. Weakness in July durable-goods orders, however, has raised concerns that business investment won't be as strong in the third quarter.

Hunger for foreign goods

Contributing to the slowdown from the first quarter was the country's trade ledger: Exports rose 9.1%, but imports grew a startling 32.4% -- the biggest jump since the first quarter of 1984. Imports took away 4.45 percentage points from GDP in the second quarter. The imports surge came as American consumers loaded up on foreign-made goods like pharmaceuticals, televisions and furniture -- the monthly change in the value of consumer good imports in May and June were the second- and third-largest increases since the series began in December 1993, according to Michelle Girard, senior economist at RBS Securities.

Also contributing to the import surge was firms importing earlier than usual because of transport bottlenecks, said Majestic's Blitz. Bernanke said in Friday's speech that the trade balance deterioration likely reflected a number of temporary and special factors that won't be the case in coming quarters. In some respects, the import surge shows the U.S. consumer wasn't completely absent in the second quarter. The value of the U.S. dollar during the three months through June increased on worries over the future of the euro zone may have contributed to Americans' renewed appetite for foreign goods.

That said, economists aren't expecting much from the U.S. consumer in the second half. Excluding gasoline and car sales, retail sales fell 0.1% in July. Worryingly high unemployment, tight credit and a moribund housing market are holding back the consumer, as is an increasing propensity to save: The savings rate climbed to 6.1% in the second quarter from 5.5% in the first quarter.

Ellen Beeson Zentner, senior U.S. macroeconomist at Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, suggested in a research note prior to the GDP report that low inflation -- the core PCE price index grew 1.1% in the second quarter -- may be having a depressing effect on spending. 'The current low-level inflation environment, while helping households cope with little or no wage growth, may itself be providing a disincentive to spend," she said.

"The economy is experiencing a broad disinflationary trend, flirting with possible deflation, which provides no incentive to take advantage of today's prices because tomorrows may be lower." Inventories didn't accumulate as quickly as the Commerce Department first estimated -- contributing 0.6 percentage points to growth, vs. the 1.1 percentage point initial contribution in the second quarter.

Profitability improves

The Commerce Department also released its first set of data on profitability in the second quarter, showing after-tax profits up 25.5%, or a 39.2% rise before tax. Publicly traded companies have already reported a banner second quarter, as earnings per share growth of the 489 components of the S&P 500 equities index that have reported results climbed 41%, according to FactSet Research data.

The domestic profits of financial corporations fell by $0.4 billion, while the domestic profits of nonfinancial companies climbed $67.9 billion. While higher than the same period of last year, first-quarter domestic profits of financial corporations grew $5.2 billion and those of nonfinancial corporations rose $117.2 billion. "Corporate profits increased but at a slower pace as well," said Joel Naroff, chief economist at Naroff Economic Advisors. "Firms may have hit the wall when it comes to productivity gains and cost cuts and now the CEOs will have to actually start managing the companies for top line growth rather than just bottom line performance. That could lead to more hiring since even in a slow growth economy you need more output."

Adding to a picture of flush corporate balance sheets, cash flows climbed 12.7% compared to the same period last year, the agency said. Of late, companies have been deploying their cash to buy other firms, with Dell Inc. and Hewlett-Packard Co. vying to buy 3Par and with BHP Billiton Ltd. launching a hostile bid for Canada's Potash Corp.

Without Government Spending, GDP Growth Would Have Been Less Than Half Of What It Was

by Vincent Fernando - Business Insider

The latest revision for U.S. Q2 GDP came in at 1.6%, which was higher than the 1.3% reading expected by consensus, but well below the 2.4% value previously reported by the government. Thing is, the latest GDP report shows just how dependent the U.S. economy was on government spending during the second quarter.

Government spending contributed +0.86% to the 1.6% GDP growth value, which was one of the highest quarterly government contribution to GDP since at least 2007. The only quarters to beat it since the beginning fo 2007 were Q3 of 2008 and Q2 of 2009, at +1.04% and +1.24% respectively. Sans the 0.86% government spending boost, U.S. GDP would have grown by just 0.74% during Q2 of this year. This is shown by the right-hand bar below.

Yes the economy is more complex than such straight subtractions, but while the exact GDP effect by government is debatable, what's clear is that Q2 relied heavily upon government spending. Government spending's +0.86% contribution accounts for more than half of GDP growth. To put this in perspective, even during all of 2009, the 'big stimulus' year, government spending only contributed +0.32% to GDP. Thus Q2's +0.86% is nothing to sneeze at relative to a tiny +1.6% total growth rate.

This sheds light on the challenge for U.S. Q3 GDP, as government spending support is expected to wane going forward.

U.S. Warfare Boosted Q2 GDP Massively

by Vincent Fernando - Business Insider

Earlier we highlighted how over half of Q2's 1.6% GDP growth could be explained by government spending. The government contributed +0.86% to the Q2 figure based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). As a follow up to that post, we've now broken out the different types of government contributions to Q2 GDP, and it turns out that defense spending was a massive component, accounting for +0.39% of the total 0.86% government GDP contribution.

Meanwhile, state consumption actually fell, sub tracing 0.10% from US GDP growth. You can see the breakdown below. Note that the numbers don't add up to precisely 0.86% due to rounding. All data is from the BEA. So a large part of Q2 GDP performance, +0.39% [of] the 1.6% total GDP growth for the U.S., was thanks to wars and general defense.

Stock markets face a 'bloodbath', warns SocGen strategist Albert Edwards

by Angela Monaghan - Telegraph

Investors should brace themselves for an equities "bloodbath" and a further fall in bond yields when the current excessive optimism propping up the market seeps away, Albert Edwards, a strategist at Société Générale, has warned. Mr Edwards said there was too much hope among investors, with excessive valuations in the US, but predicted it would come to an end in the coming months as economic data increasingly pointed to a double-dip recession.

"Equity investors are in for a rude shock. The global economy is sliding back into recession and they are still not even aware that these events will trigger another leg down in valuations, the third major bear market since the equity valuation bubble burst," he said.

Government bonds, which are considered lower risk assets compared with equities, have remained in demand during the crisis and yields are at a low level by historical standards - where low yields indicate strong demand. The yield on UK benchmark 10-year bonds was 2.88pc yesterday, and Mr Edwards forecast a further fall to below 2pc. He predicted that "global cyclical failure" would push US 10-year yields down to 1.5pc-2pc, and German bunds to below 1.5pc.

"So far the equity market has shrugged off much of the weaker data that abounds, and has not joined the bond market in a perceptive move. "The equity market will though crumble like the house of cards it is, when the nationwide [US] manufacturing ISM slides below 50 into recession territory in coming months." The ISM index fell to 55.5 in July from 56.2 in June.

Mr Edwards forecast a return to the "valuation nadir last seen in 1982", with the S&P bottoming at around 450.

The Fed Is In A Box, And The Next Round Of Quantitative Easing Won't Do Anything

by The Pragmatic Capitalist

Apparently I am not the only one who believes quantitative easing is a "non-event". In a recent note UniCredit analysts describe why they believe the Fed is out of bullets and will have little to no impact on markets with its "creative"new forms of monetary policy:"There are, however, two factors that suggest the yield effect will be smaller than calculated. When the US central bank began with the first round of the quantitative/credit easing in autumn 2008, the financial markets were still in panic mode. In the wake of the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the escalating economic crisis, a complete collapse of the financial markets even appeared to be a distinct possibility. The risk premiums for all asset classes were correspondingly high at the time – also for Treasuries.

Thanks to its resolute intervention, the Fed was able to restore a certain degree of basic confidence on the market. The probability of a collapse was averted, and the risk premium fell dramatically. Today, in contrast, the risk premium is already very low. The possible yield effect of additional quantitative easing would, therefore,come exclusively via the higher demand for Treasuries (portfolio balance effect).

The second factor that suggests yields would fell less strongly than suggested by the NY Fed model is the law of diminishing returns: The more Treasury securities the US central bank already holds, the lower the effect of further purchases becomes. Net for net, we therefore assume that even a massive additional program for the purchase of Treasury securities totaling one trillion USD would lower the yield level by only approximately 25 basis points."

UniCredit correctly argues that lower rates are unlikely to fix the system because the lending markets are effectively clogged:"Lower interest rates stimulate the economy via different transmission channels. Some of these channels are, however, clogged, thereby reducing the impulse of a more expansive monetary policy on the economy as a whole. A study conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco shows that lower interest rates influence the real economy primarily through four channels: (i) the cost of borrowing, (ii) the supply of credit, (iii) household wealth and (iv) the exchange rate.

Because of the after-shocks of the housing market crisis, households are profiting only to a limited extent from lower capital market rates. The reason for the reluctance of businesses to invest is the uncertainty concerning the economy and regulatory aspects. Not even lower interest rates can change this."

UniCredit believes this is a major "paradigm shift"in the way markets view monetary policy. In essence, the Fed is impotent and the markets are only just beginning to realize this:"Are we possibly now experiencing a "paradigm shift", in which the monetary policy possibilities of the Fed are, in principle, being assessed more negatively? Under the aegis of former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan and also under his successor Ben Bernanke, the term "Greenspan put" has become established to describe the "psychological impact"of the way the Fed reacts to economic downswings and crises. It describesthe basic assessment of investors that the Fed will rapidly counter-steer with monetary policy in the event of economic downswings or crises and thereby limit the downside risk for risky assets – first and foremost equities.

The presumed Greenspan put was practiced successfully for example after the October 1987 crash as well as after the LTCM and Asian crisis. The widespread view is that this increases the willingness of investors to assume risk and tends to lower the demanded risk premium of equity investments. Must investors now again arrive at a more negative assessment with respect to the future possibilities of the Fed? When it comes to the performance of the equity market on rate cuts, there were in recent years already interesting changes that favor a rethink."

Of course, I entirely agree with the above analysis and it’s nice to see a large firm finally issuing a note that accepts the fact that this is a non-event as opposed to the constant misguided fear mongering about "money printing"and "monetization"that we hear from all other camps. The bottom line according to UniCredit – The Fed is becoming powerless and that could become very disconcerting to the equity markets:"Bottom line: There are, in our view, plausible arguments supporting skepticism towards the economic efficacy of any further easing of US monetary policy. There is, therefore, the risk that going forward investors will be much more pessimistic in their assessment of the Fed’s ability to counter-steer using its monetary policy in the event of an economic slowdown. This would be tantamount to a paradigm shift from the "Greenspan put"to the "powerlessness"of the US central bank – with negative ramifications for the equity markets in the USA and Europe."

Camille Reinhart: Recovery To Be Slow, High Unemployment To Last A Decade

by Sewell Chan - New York Times

The American economy could experience painfully slow growth and stubbornly high unemployment for a decade or longer as a result of the 2007 collapse of the housing market and the economic turmoil that followed, according to an authority on the history of financial crises. That finding, contained in a new paper by Carmen M. Reinhart, an economist at the University of Maryland, generated considerable debate during an annual policy symposium here, organized by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, which concluded on Saturday.

The gathering, at a historic lodge in Grand Teton National Park, brought together about 110 central bankers and economists, including most of the Federal Reserve’s top officials. In 2008, the symposium occurred weeks before the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy nearly shut down the financial markets. At the symposium last year, officials congratulated themselves on weathering the worst of the crisis.

But the recent slowing of the recovery cast a pall on this year’s gathering. As economists (some wearing jeans and cowboy boots) conferred on a terrace with a sweeping view of the 13,770-foot peak of Mount Teton, or watched a horse trainer tame an unruly colt at a nearby ranch, they anxiously discussed research like Ms. Reinhart’s. (Participants pay to attend the event, which is not financed by taxpayers, a Kansas City Fed spokeswoman emphasized.)

"I’m more worried than I have ever been about the future of the U.S. economy,"said Allen Sinai, co-founder of the consulting firm Decision Economics and a longtime participant in the symposium. "The challenge is unique: poor and diminishing growth, a sticky unemployment rate, sky-high deficits and a sovereign debt that makes us one of the most fiscally irresponsible countries in the world."

Ms. Reinhart’s paper drew upon research she conducted with the Harvard economist Kenneth S. Rogoff for their book "This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly,"published last year by Princeton University Press. Her husband, Vincent R. Reinhart, a former director of monetary affairs at the Fed, was the co-author of the paper. The Reinharts examined 15 severe financial crises since World War II as well as the worldwide economic contractions that followed the 1929 stock market crash, the 1973 oil shock and the 2007 implosion of the subprime mortgage market.

In the decade following the crises, growth rates were significantly lower and unemployment rates were significantly higher. Housing prices took years to recover, and it took about seven years on average for households and companies to reduce their debts and restore their balance sheets. In general, the crises were preceded by decade-long expansions of credit and borrowing, and were followed by lengthy periods of retrenchment that lasted nearly as long.

"Large destabilizing events, such as those analyzed here, evidently produce changes in the performance of key macroeconomic indicators over the longer term, well after the upheaval of the crisis is over,"Ms. Reinhart wrote. Ms. Reinhart added that officials may err in failing to recognize changed economic circumstances. "Misperceptions can be costly when made by fiscal authorities who overestimate revenue prospects and central bankers who attempt to restore employment to an unattainably high level,"she warned.

Several scholars here cautioned that it was premature to infer long-term economic woes for the United States from the aftermath of past crises. The Reinharts’ research "has not yet tried to assess the extent to which different policy stances mitigated the length of the outcome,"said Susan M. Collins, an economist and the dean of the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan. "But the reality is that we need to have an understanding that the issues we are dealing with are severe, and that we should not expect them to be unwound in a few months."

Ms. Collins added: "I’m very much a glass-half-full person. What we’ve seen in the past few years has been a policy success. Things are not where we want them to be, but they could have been a lot worse."The Reinharts’ paper was not the only one to offer somber implications for policy makers. Two economists, James H. Stock of Harvard and Mark W. Watson of Princeton, presented a paper arguing that inflation, which has already fallen so much that some Fed officials fear the economy is at risk of deflation, a cycle of falling prices and wages, could fall even further by the middle of next year.

Inflation has been running well below the Fed’s unofficial target of about 1.5 percent to 2 percent. Ben S. Bernanke, the Fed chairman, reiterated on Friday that the central bank would "strongly resist deviations from price stability in the downward directions."Mr. Stock and Mr. Watson noted that recessions in the United States were associated with declines in inflation, with an exception being an increase in inflation in 2004, which occurred despite a "jobless recovery"from the 2001 recession. The authors said they could not explain the anomaly but also could not "offer a reason why it might happen again."

September: The Cruelest Month

by PragCap

Except for a brief counter-trend rally in July, the stock market has struggled since peaking in late April. Investors are concerned. For some perspective, today’s chart presents the Dow’s average performance for each calendar month since 1950. As today’s chart illustrates, it is not unusual for the stock market to underperform during the May to October time frame with a brief counter-trend rally occurring in July. It is worth noting that the worst calendar month for stock market performance (i.e. September) is fast approaching.

Widespread Fear Freezes Housing Market

by Joe Nocera - New York Times

You have to wonder sometimes what they’re smoking over there at the National Association of Realtors. On Tuesday, the self-proclaimed "voice for real estate"released its "existing home sales"figures for July. They were gruesome. Sales were down 27 percent from the previous month, and down 26 percent from a year ago. Annualized, the July sales figures would translate into fewer than 3.9 million homes sold this year — a staggeringly low figure. (The record high occurred in 2005, when more than seven million houses were sold.)

The months-to-sale number was depressingly high; the Realtors group reported that it now takes more than a year to sell a typical house, compared with six months in a normal market. The amount of inventory is high. Lest we forget, these awful numbers are coming out at a time when the financial incentive to buy could hardly be stronger: the fixed rate on a 30-year mortgage is at an incredibly low 4.36 percent, according to an authoritative survey conducted by Freddie Mac.Yet here was Lawrence Yun, the association’s chief economist, trying to turn lemons into lemonade: "Given the rock-bottom mortgage interest rates and historically high housing affordability conditions, the pace of a sales recovery could pick up quickly, provided the economy consistently adds jobs,"he said in a news release. Mr. Yun went on to attribute the weak July numbers to the expiration of the Obama administration’s tax credit for home buyers. They had caused consumers to "rationally"jump into the market during the first half of the year — at the expense of summer sales, he said.

The post-tax-credit slump, he predicted, would be over by the fall, and by the end of the year, five million existing homes would be sold. ("To place in perspective, annual sales averaged 4.9 million in the past 20 years,"he said.) Mr. Yun also predicted that home values would not fall much further, since they were "back in line relative to income."In other words, the July numbers were a mere blip.

Clearly, Mr. Yun needs to get out a little more often. Specifically, he ought to talk to people on the ground — like mortgage lenders or prospective borrowers. Talking to these people would probably give him a more sober take on the larger meaning of the latest sales numbers for existing homes. Sometimes, you see, lemons really can’t be turned into lemonade.

•

"In the financial markets, a lack of liquidity immediately leads to falling prices,"said Lou Barnes, the founder of Boulder West Financial Services. (Boulder West was acquired last year by Premier Mortgage Group.) "In the real estate market, something different happens,"he added. "Illiquid real estate markets freeze."That is what is happening now. For months, the Obama tax credit had been the only grease in the housing market. Now that it is gone, the buying and selling of houses is essentially grinding to a halt.

Why is this happening? Just as the subprime bubble of 2006 and 2007 required one kind of perfect storm — namely, incentives to throw underwriting standards out the window — we are now living through the opposite kind of perfect storm. Essentially, every participant in the housing market has a reason to be afraid. And that fear is paralyzing.

The prospective buyer, for instance, has two good rationales to fear buying a new home. One is the unemployment rate. "A major psychological thing happens with high unemployment,"says Dave Zitting, a veteran mortgage banker and founder of Primary Residential Mortgages. "Those with a job worry about whether they are going to keep that job"— which, in turn, prevents them from taking the plunge on a new home.

The second reason is that, Mr. Yun notwithstanding, most people simply do not believe that housing prices are even close to hitting bottom. "In the Bay Area, a house that was worth $300,000 a decade ago became a million-dollar home,"said Greg Fielding, a real estate broker and blogger. "Now it is listed at $800,000."That price, he suggested, was still unrealistically high. The seller, meanwhile, doesn’t want to face the fact that his or her home is too richly priced, and won’t sell at a more realistic price — which may well be below his or her mortgage debt.

There is also an immense amount of inventory that has yet to hit the market but will, sooner or later. People in the real estate business have taken to calling this "the shadow inventory."It consists of homes for which the owners have stopped paying the mortgage but the banks haven’t foreclosed on yet, foreclosed properties that have not yet been put up for sale, homes with modified mortgages that the owners still can’t afford and will soon default on and so on.

Mr. Barnes describes the shadow inventory as akin to "ranks of Napoleonic infantry, rows deep, hidden in the fog."This inventory, estimated by Rick Sharga of RealtyTrac to be between three million and four million homes, is almost certain to drag down home prices for the foreseeable future. "The disinterest of buyers, in an interest-rate environment that may be the lowest ever, is striking,"Mr. Barnes said. But, he added, it makes perfect sense. Since 2007, housing prices have been in a deflationary spiral, and nobody can say when it will end. "It doesn’t matter if interest rates go down to 2 percent,"Mr. Barnes said — buyers won’t reappear in big numbers until they can see the light at the end of the tunnel.

So that is what it looks like for the prospective borrower. Now look at it from the lender’s perspective. Chastened by the excesses of the bubble, mortgage lenders have swung hard in the other direction, becoming excessively, almost insanely, conservative. They demand high FICO scores. They won’t lend to anyone who is recently self-employed — even if the potential borrower has socked away a lot of money in the bank, or is making a good income. They won’t count income from capital gains.

"I have wonderful people in my office every day who would have qualified for a loan prior to the bubble"but now can’t get one, Mr. Zitting said. Mr. Barnes said: "Underwriting standards are vastly tighter than any time in my lifetime. It is choking off buyers."Here’s the strangest part, though: it is really not the lenders themselves who are imposing the most draconian of these tight new underwriting standards. Rather, it is the federal government. That’s right, the government.

At the same time that the administration was offering a hefty tax credit to spur home sales, the government’s wholly owned subsidiaries, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, were imposing rules that made it increasingly difficult to buy a home. And Fannie and Freddie have the ultimate say these days because without their guarantee, Wall Street securitizers won’t buy a mortgage from a bank — because Wall Street is just as fearful as every other participant in the market.

"The government right now is insuring something like 85 to 90 percent of the country’s mortgages,"said Daniel Alpert, a managing director of Westwood Capital. And given the enormous losses Fannie and Freddie were saddled with during the financial crisis, they are in no mood to take risks, not even on borrowers who are normally considered creditworthy. So they are saying no a lot more than they used to — even though this is having a terrible effect on the housing market.

It’s even become nearly impossible for well-heeled investors to buy rental properties. This is no small matter. At the peak of the bubble, the rate of homeownership approached 70 percent. Now it is falling toward 65 percent — which is more or less where it was before all the housing madness of the last decade. That means that millions of Americans who were briefly homeowners need to become renters again. They need a place to rent.

But somebody has to buy the homes they are leaving behind and turn them into rental properties. The most likely buyer is a professional investor who purchases rental properties for a living. Yet, absurdly, government rules have made it exceedingly difficult to make loans to investors who want to buy up rental properties. This only adds to the shadow inventory.

A few weeks ago, some of the better known financial bloggers had a background briefing at the Treasury Department with officials who included Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner. In their blog posts after the meeting, they did not, alas, describe a government strategy that called for loosening Fannie’s and Freddie’s overly cautious standards — the obvious short-term solution. Instead they described a Treasury housing strategy that was essentially a play for time.

The tax credit for home buyers; the willingness to look the other way as banks refused to foreclose, pretending that the owners still planned to pay their mortgage; the half-baked government mortgage modification programs — they were all aimed at buying time until the economy recovered and employment picked up. At which point, they hoped, the housing market would have achieved enough lift that it could take off on its own.

At the end of June, though, the tax credit disappeared — and that’s when time ran out. On Friday, the new G.D.P. numbers came out, confirming what everybody already knew. The economy has not recovered — not even close. If the housing market is like an airplane on a runway, it is far more likely to crash at this point than it is to take off. That is why the July numbers are so scary to those in the housing business.

On the ground, they don’t look like a blip. They look like a very painful future.

Home Prices May Drop Another 25%

by Daniel Indiviglio - TheAtlantic.com

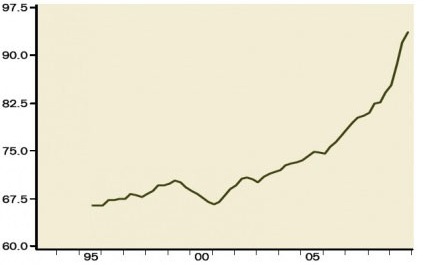

With all the talk of the awful sales numbers for both existing and new homes in July, there was one small kernel of seeming good news: existing home prices rose slightly. The national median home price actually increased by 0.7% last month compared to a year earlier, according to the National Association of Realtors. But don't expect this trend to continue -- prices still have a ways to fall before they settle at their natural level.Several weeks ago, Barry Ritholtz posted the following chart. It was originally featured by the New York Times, and updated by a commenter to Ritholtz's blog named Steve Barry.

This is a pretty fascinating picture. First, it shows just how incredibly absurd the housing boom was. Beginning in the 1940s, inflation-adjusted homes prices have settled around the 110 value according to the Case-Shiller index. Yet, the index value exceeded 200 in 2006. Prices began a descent when housing collapsed, but as of May the index remained well above the natural value of 110.

Eyeing the chart, the value looks to have hit around 147 in May. For it to drop back down to 110, home prices would have to decline another 25%. That's still a pretty long way to fall.

Of course, inflation could help it get there. If the price level does rise in the years to come as some economists expect, then even if home prices remain constant, inflation-adjusted values will be lower. That will provide little consolation to current homeowners, however, as their house's relative value as an investment will be lower than alternative investments that kept with or exceeded the rate of inflation.

New mortgage delinquencies rise again

by E. Scott Reckard and Alejandro Lazo - Los Angeles Times

Adding to worries about the economy's direction, the number of newly delinquent home loans has risen for two straight quarters in what could foreshadow another surge in unemployment-related foreclosures. The consequences of the increase in fresh delinquencies are uncertain. But the rise presents a troubling counterpoint to positive trends in severely delinquent loans and foreclosures, which, although still at very high levels, have begun to decline, the Mortgage Bankers Assn. said Thursday.

The data release helped push the Dow Jones industrial average down 74 points, causing the index to close below 10,000 for the first time in seven weeks. The delinquency report followed news this week of unexpectedly sharp declines in home sales despite record-low mortgage interest rates. Freddie Mac said Thursday that the average rate available on a 30-year fixed-rate loan fell this week to 4.39%, the lowest level in the nearly four decades that the mortgage giant has been tracking home loan interest costs.

Economists attributed the increase in newly delinquent mortgages to the country's persistently high unemployment. "It takes a paycheck to make a mortgage payment," said Jay Brinkmann, chief economist for the Mortgage Bankers Assn. He said the trend could lead to another increase in foreclosures if the employment picture doesn't brighten soon. "Unfortunately, since April, there has been almost no job growth at all, so I think that is where the risk lies looking forward," said Christopher Low, chief economist at Chicago investment firm FTN Financial.

The declines in serious delinquencies and foreclosures were caused in part by a since-expired federal tax credit for home purchases, Brinkmann said. The credit caused a brief spike in sales, allowing some late-paying borrowers to catch up by selling their properties. Other factors cited by Brinkmann: successful loan modifications and the decrease in new delinquencies last year, which meant that fewer bad loans were moving toward foreclosure. Now, he said, two of those three contributors to the improving picture have disappeared.

The mortgage bankers group said the percentage of newly delinquent mortgages — defined as at least 30 but less than 60 days in arrears — fell for three straight quarters last year from a peak of 3.77% but then reversed course this year and stood at 3.51% in the April-to-June period. Economists are closely watching the huge category of loans in foreclosure or at least 90 days past due. The numbers of such mortgages had swelled because of moratoriums on foreclosures and trial loan modifications, many of which have not provided permanent relief for borrowers.

There were about 4.5 million of these loans at the end of June, about the same as the number of houses for sale, Brinkmann said. Citing a high rate of unsuccessful loan modifications, some economists say the homes financed by these loans could eventually flood the market, prompting home prices to fall after stabilizing in many areas.

These severely troubled loans fell from 9.54% of all mortgages at the end of March to 9.11% in June. Lenders began foreclosure proceedings on 1.11% of all loans in the second quarter, down from 1.23% in the first quarter. One reason new foreclosure proceedings are down is that some banks have pushed back foreclosures in a bid to avoid flooding the market with steeply discounted properties, said economist Sean O'Toole at data tracker ForeclosureRadar.

In addition, some mortgage servicers may be waiting to see the effect of emergency economic aid the Obama administration has provided to states, said Douglas Robinson, spokesman for NeighborWorks America, a foreclosure counseling group. "We don't think that the decline in foreclosure filings is due to any serious change in the economy or in the housing outlook," he said. He predicted that increases in monthly payments on some interest-only and "pay option" mortgages, coupled with high unemployment, would create "the next wave of foreclosure" late this year.

The Case Against Homeownership

by Barbara Kiviat - Time

Homeownership has let us down. For generations, Americans believed that owning a home was an axiomatic good. Our political leaders hammered home the point. Franklin Roosevelt held that a country of homeowners was "unconquerable." Homeownership could even, in the words of George H.W. Bush's Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Jack Kemp, "save babies, save children, save families and save America." A house with a front lawn and a picket fence wasn't just a nice place to live or a risk-free investment; it was a way to transform a nation. No wonder leaders of all political stripes wanted to spend more than $100 billion a year on subsidies and tax breaks to encourage people to buy.

But the dark side of homeownership is now all too apparent: foreclosures and walkaways, neighborhoods plagued by abandoned properties and plummeting home values, a nation in which families have $6 trillion less in housing wealth than they did just three years ago. Indeed, easy lending stimulated by the cult of homeownership may have triggered the financial crisis and led directly to its biggest bailout, that of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Housing remains a drag on the economy. Existing-home sales in July dropped 27% from the prior month, exacerbating fears of a double-dip. And all that is just the obvious tale of a housing bubble and what happened when it popped. The real story is deeper and darker still.

For the better part of a century, politics, industry and culture aligned to create a fetish of the idea of buying a house. Homeownership has done plenty of good over the decades; it has provided stability to tens of millions of families and anchored a labor-intensive sector of the economy. Yet by idealizing the act of buying a home, we have ignored the downsides. In the bubble years, lending standards slipped dramatically, allowing many Americans to put far too much of their income into paying for their housing. And we ignored longer-term phenomena too.

Homeownership contributed to the hollowing out of cities and kept renters out of the best neighborhoods. It fed America's overuse of energy and oil. It made it more difficult for those who had lost a job to find another. Perhaps worst of all, it helped us become casually self-deceiving: by telling ourselves that homeownership was a pathway to wealth and stable communities and better test scores, we avoided dealing with these formidable issues head-on.

Now, as the U.S. recovers from the biggest housing bust since the Great Depression, it is time to rethink how realistic our expectations of homeownership are — and how much money we want to spend chasing them. As members of both government and industry grapple with re-envisioning Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the rest of the housing finance system, many argue that homeownership should not be a goal pursued at all costs.

An Autopsy of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

by Binyamin Appelbaum - New York Times

Here’s a last-minute option for summer reading material: An autopsy on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by their overseer, the Federal Housing Finance Agency.The report aims to inform the continuing debate in Washington about the future of the government’s role in housing finance. It’s not hard sledding, just 15 pages of bullet points and charts. And it does a good job of making a few key points:

1. Fannie and Freddie did not cause the housing bubble. In fact, you can think of the bubble as all the money that poured into the housing market on top of their regular and continuing contributions. There’s a good chart on Page 4 of the report illustrating this:

Source: Inside Mortgage Finance, Q1 2010 data not available The market share of the two government-sponsored companies plunged after 2003, and did not recover until 2008. In 2006, at the peak of the mania, the companies subsidized only one-third of the mortgage market.

2. This was not for a lack of trying. The companies bought and guaranteed bad loans with reckless abandon. Their underwriting standards jumped off the same cliff as every other participant in the mortgage market.

3. Importantly, the companies’ losses are mostly in their core business of guaranteeing loans, not in their investment portfolios. The guarantee business is the reason the companies were created. Fannie and Freddie buy loans from banks and other lenders, and then sell packages of those loans to investors with a promise to cover any losses. That pulls money into mortgage lending and helps hold down interest rates. During the boom, the companies also built large portfolios of investments in mortgage-related securities to boost profitability.

Some proponents of federal subsidies for mortgage lending have argued that the companies went off the rails by pursuing investments on the side, but that their basic guarantee business was sound. The implication is that the business model can be salvaged.

The government report shows clearly that the guarantee business was rotten, too. Draw what lessons you will.

Procrastination on Foreclosures, Now 'Blatant,' May Backfire

by Jeff Horwitz and Kate Berry - American Banker

Ever since the housing collapse began, market seers have warned of a coming wave of foreclosures that would make the already heightened activity look like a trickle. The dam would break when moratoriums ended, teaser rates expired, modifications failed and banks finally trained the army of specialists needed to process the volume. But the flood hasn't happened. The simple reason is that servicers are not initiating or processing foreclosures at the pace they could be.

By postponing the date at which they lock in losses, banks and other investors positioned themselves to benefit from the slow mending of the real estate market. But now industry executives are questioning whether delaying foreclosures — a strategy contrary to the industry adage that "the first loss is the best loss" — is about to backfire. With home prices expected to fall as much as 10% further, the refusal to foreclose quickly on and sell distressed homes at inventory-clearing prices may be contributing to the stall of the overall market seen in July sales data. It also may increase the likelihood of more strategic defaults.

It is becoming harder to blame legal or logistical bottlenecks, foreclosure analysts said. "All the excuses have been used up. This is blatant," said Sean O'Toole, CEO of ForeclosureRadar.com, a Discovery Bay, Calif., company that has been documenting the slowdown in Western markets.

Banks have filed fewer notices of default so far this year in California, the nation's biggest real estate market, than they did 2009 or 2008, according to data gathered by the company. Foreclosure default notices are now at their lowest level since the second quarter of 2007, when the percentage of seriously delinquent loans in the state was one-sixth what it is now. New data from LPS Applied Analytics in Jacksonville, Fla., suggests that the backlog is no longer worsening nationally — but foreclosures are not at the levels needed to clear existing inventory.

The simple explanation is that banks are averse to realizing losses on foreclosures, experts said. "We can't have 11% of Californians delinquent and so few foreclosures if regulators are actually forcing banks to clean assets off their books," O'Toole said.

Officially, of course, this problem shouldn't exist. Accounting rules mandate that banks set aside reserves covering the full amount of their anticipated losses on nonperforming loans, so sales should do no additional harm to balance sheets. Within the last two quarters, many companies have even begun taking reserve releases based on more bullish assumptions about the value of distressed properties. Now there is widespread reluctance to test those valuations, an indication that banks either fear they have insufficient or are gambling for a broad housing recovery that experts increasingly say is not coming.

Banks did not choose the strategy on their own. With the exception of a spike in foreclosure activity that peaked in early-to-mid 2009, after various industry and government moratoriums ended and the Treasury Department released guidelines for the Home Affordable Modification Program, no stage of the process has returned to pre-September 2008 levels. That is when the Treasury unveiled the Troubled Asset Relief Program and promised to help financial institutions avoid liquidating assets at panic-driven prices. The Financial Accounting Standards Board and other authorities followed suit with fair-value dispensations.

These changes made it easier to avoid fire-sale marks — and less attractive to foreclose on bad assets and unload them at market clearing prices. In California, ForeclosureRadar data shows, the volume of foreclosure filings has never returned to the levels they had reached before government intervention gave servicers breathing room. Some servicing executives acknowledged that stalling on foreclosures will cause worse pain in the future — and that the reckoning may be almost here.

"The industry as a whole got into a panic mode and was worried about all these loans going into foreclosure and driving prices down, so they got all these programs, started Hamp and internal mods and short sales," said John Marecki, vice president of East Coast foreclosure operations for Prommis Solutions, an Atlanta company that provides foreclosure processing services. Until recently, he was senior vice president of default administration at Flagstar Bank in Troy, Mich. "Now they're looking at this, how they held off and they're getting to the point where maybe they made a mistake in that realm."

Moreover, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have increased foreclosures in the past two months on borrowers that failed to get permanent loan modifications from the government, according to data from LPS. If the government-sponsored enterprises' share of foreclosures is increasing, that implies foreclosure activity by other market participants is even less robust than the aggregate. "The math doesn't bode well for what is ultimately going to occur on the real estate market," said Herb Blecher, a vice president at LPS. "You start asking yourself the question when you look at these numbers whether we are fixing the problem or delaying the inevitable."

Blecher said the increase in foreclosure starts by the GSEs "is nowhere near" what is needed to clear through the shadow inventory of 4.5 million loans that were 90 days delinquent or in foreclosure as of July 31. LPS nationwide data on foreclosure starts reflects the holdup: Though the GSEs have gotten faster since the first quarter, portfolio and private investors have actually slowed. "What we're seeing is things are starting to move through the system but the inflows and outflows are not clearing the inventory yet," he said.

Delayed foreclosures might be good news for delinquent borrowers, but it comes at a high price. Stagnant foreclosures likely contributed to the abysmal July home sales, since banks are putting fewer homes for sale at market-clearing prices. Moreover, Freddie says a good 14% of homes that are seriously delinquent are vacant. In such circumstances, eventual recovery values rapidly deteriorate. Defaulted borrowers were spending an average of 469 days in their home after ceasing to make payments as of July 31, so the financial attraction of strategic defaults increases.

One possible way banks are dealing with that last threat is through what O'Toole calls "foreclosure roulette," in which banks maintain a large pool of borrowers in foreclosure but foreclose on a small number at random. O'Toole said the resulting confusion would make it harder for borrowers to evaluate the costs and benefits of defaulting and fan fears that foreclosure was imminent.

Two Charts: All You Need To Know About Canada’s Housing Bubble

by VREAA

First chart: Income and House prices

Second chart: Canada’s Household Debt to GDP Ratio

- Study and compare.

- Note cause of our bubble.

- Any more questions?

[sources: First Chart from Alexandre Pestov's 'The Elusive Canadian Housing Bubble', Summer 2010 edition, July 2010; Second Chart adapted from one in a letter from David Rosenberg, and previously headlined 7 May 2010]

How Obama got rolled by Wall Street

by Michael Hirsh - Newsweek

Obama’s Old Deal: Why the 44th president is no FDR—and the economy is still in the doldrums.

Barack Obama was "incredulous" at what he was hearing, said one of his top economic advisers. The president had spent his first year in office overseeing the biggest government bailout of the financial industry in American history. Together with Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke, he had kept Wall Street afloat on a trillion-dollar tide of taxpayer money. But the banks were barely lending, and the economy was still mired in high unemployment.

And now, in December 2009, the holiday news had started to filter out of the canyons of lower Manhattan: Wall Street’s year-end bonuses would actually be larger in 2009 than they had been in 2007, the year prior to the catastrophe. "Wait, let me get this straight," Obama said at a White House meeting that December. "These guys are reserving record bonuses because they’re profitable, and they’re profitable only because we rescued them." It was as if nothing had changed. Even after a Depression-size crash, the banks were not altering their behavior. The president was being perceived, more and more, as a man on the wrong side of an incendiary issue.

And so, prodded forward by Vice President Joe Biden—the product of a working-class upbringing in Scranton, Pa.—the president began to consider getting tougher on Wall Street. "We kept revisiting it," said the economic adviser (who recounted details of the meetings only on condition of anonymity). One big proposal the White House hadn’t adopted was Paul Volcker’s idea of barring commercial banks from indulging in heavy risk taking and "proprietary" trading. In Volcker’s view, America’s major banks, which enjoy federal guarantees on their deposits, had to stop putting taxpayer money at risk by acting like hedge funds.

This had become a grand passion for Volcker, a living legend renowned for crushing inflation 30 years before as Fed chairman. He had long been skeptical of financial deregulation. Beyond the ATM, Volcker asked, what new banking products had really added to economic growth? Exhibit one for this argument was derivatives, trillions of dollars in "side bets" placed by Wall Street traders. "I wish somebody would give me some shred of neutral evidence about the relationship between financial innovation recently and the growth of the economy," he barked at one conference.

Yet for most of that first year, Obama and his economic team had largely ignored Volcker, a sometime adviser. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner and chief economic adviser Larry Summers still questioned whether Volcker’s proposals were feasible. Now Obama was pressing them—very gingerly—to reconsider. "I’m not convinced Volcker’s not right about this," Obama said at one meeting in the Roosevelt Room. Biden, a longtime fan of Volcker’s, bluntly piped up: "I’m quite convinced Volcker is right about this!"

Obama’s cautious, late embrace of Volcker was all too typical. He had arrived in office perceived by some as the second coming of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Yet Obama hadn’t acted much like FDR in the ensuing months. Instead he had faithfully channeled Summers and Geithner and their conservative approach to stimulus and reform. Early on, Obama’s two key economic officials had argued down Christina Romer, the new chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisers, when she suggested a massive $1.2 trillion stimulus to make up for the collapse of private demand.

They opted for slightly less than $800 billion. "We believe that this is a properly sized approach to move the economy forward," said Summers, who didn’t want to expand the federal deficit or worry the bond market. With the recession still darkening their outlook, Summers and Geithner also didn’t want to tamper too much with what they still saw as the economy’s engine room: Wall Street. Partly on their advice, the president "explicitly decided not to break up all big financial institutions," said another top economic adviser, Austan Goolsbee.

After his first year, Obama felt he had done well overall on the economy. Helped by Fed chairman Bernanke, his administration had brought the financial system back from the abyss—from another Great Depression, in effect—by shoring up the banks with hundreds of billions in new bailouts. The administration also pushed for a broad array of reforms. The giant bill Obama signed early in the summer of 2010 brought trillions of dollars in "dark" trading in over-the-counter derivatives into the open. It created new, tough watchdogs for credit-card and mortgage companies, as well as banks. It gave the government new powers to liquidate failing financial firms rather than bail them out.

The president proudly called the new law "the toughest financial reform since the one we created in the aftermath of the Great Depression." What Obama left unsaid was that his administration had argued against many of the toughest amendments in the bill. And Wall Street, in the end, didn’t complain about it all that much. The biggest firms knew that much of what their powerful lobbyists had failed to block or water down in the bill could be taken care of later on. They’d still be able to influence the vast set of rules on capital, leverage, and other financial issues that would be written by regulators.

Led by Summers and Geithner, Obama’s economic team resisted almost every structural change to Wall Street—in particular, Volcker’s plan (initially) and Arkansas Sen. Blanche Lincoln’s idea to bar banks from swaps trading. The administration’s program for getting underwater mortgage holders out of trouble was also criticized as too modest. Obama’s team accepted "too many givens," says a former senior career Fed official who asked to remain anonymous so as not to offend his former colleagues. Obama’s effort "certainly wasn’t like FDR’s because reform wasn’t driven by the White House," says Michael Greenberger, a former senior regulator who did much to shape derivatives legislation behind the scenes. "If anything, during most of the journey the White House was a problem and Treasury was a problem."

Obama’s aides claimed they were only making necessary compromises, placating the Republicans and centrist Democrats they needed to pass the law. And they did stand firm on creating a strong Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. But by midsummer of 2010 the Volcker rule that Obama finally backed was so full of exemptions—allowing banks to invest substantially in hedge and equity funds—that even Volcker expressed dismay. The fundamental structure of Wall Street had hardly changed. On the contrary, the new law effectively anointed the existing banking elite, possibly making them even more powerful. The major firms got to keep the biggest part of their derivatives business in interest-rate and foreign-exchange swaps. (JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Bank of America, and Morgan Stanley control more than 95 percent, or about $200 trillion worth, of that market.)

The same banks may end up controlling or at least dominating the clearinghouses they are being pressed to trade on as well. New capital charges, meanwhile, have created barriers to entry for new firms. This consolidation of the elites has in turn kept alive the "too big to fail" problem. "It makes it way tougher now to kiss somebody off when they get in trouble," says the former Fed official. Eugene Ludwig, a former comptroller of the currency, believes the new law’s impact will be "profound" in changing the way banks do business. But he worries about a "skewing of the playing field" in favor of the big banks, putting community banks at a disadvantage.

The Obama administration also did little to use its bully pulpit to reorient pay packages at the big financial houses, where bonuses still often run in the tens of millions of dollars. Critics make the case that changing this pay structure would do more than punish those who helped spur the meltdown. It might also encourage some of America’s greatest minds to stay away from financial engineering, which contributes little of substance to the economy, and instead consider real engineering. Nor has the Justice Department launched prosecutions as it did after the S&L crisis, or during the insider-trading scandals of the ’80s, when Michael Milken and Ivan Boesky were led off in handcuffs. (One problem this time around, lawyers say, is that virtually everyone was complicit in the subprime-mortgage scam.)

Most significantly, Barack Obama, in contrast to FDR in the depths of the Depression, has failed as yet to restore confidence in the economy. A recent Associated Press poll showed him at his lowest point ever on that issue, with just 41 percent of Americans approving of his performance. It was little surprise last week when Republican House leader John Boehner, sensing blood in the water—and a possible speakership in his future—attacked the president’s economic team and called for the resignations of Geithner and Summers. (Both budget chief Peter Orszag and Romer had already announced over the summer they were leaving.)

Obama can hardly take all the blame for the surprising persistence of high unemployment and slow growth. Among the new headwinds beating the economy down in recent months was Europe’s currency crisis, for example. But the leadership question can’t be ignored. Financial and economic reform just never seemed to be a subject that kindled Obama’s passions, his critics say. (The White House strenuously disagrees: "Financial reform has been a top priority to the president since day one," administration spokeswoman Jennifer Psaki told me.)

For much of his first 18 months in office, Obama always seemed to be finding some new thing to focus on. He spoke about financial reform, but he often seemed to address it on the fly, as he was tackling other priorities, like health care. To be fair, Obama was also juggling two wars. Yet all in all, he seemed perfectly willing to leave things to his trusted lieutenants, Geithner and Summers, puzzling some Democratic allies on the Hill. "Doesn’t the president realize he’s got a big flank exposed here?" said one Democratic staffer pushing for tougher restrictions on Wall Street early in the summer of 2010.

There was so much passion and ambition in Obama’s words about fixing the economy, and so much dispassion and caution in his policy choices. Early in the Democratic primaries, in January 2008, Obama had stunned many of his supporters by praising Reagan as a transformational president—a contrast to the eight years of Bill Clinton, Obama added cuttingly. Reagan, Obama said, "put us on a fundamentally different path because the country was ready for it." Yet at what would seem to be a similar historical inflection point—what should have been the end of Reaganism, or deregulatory fervor—President Obama seemed unprepared to address the deeper ills of the financial system and the economy.

Several officials who have worked with the Obama team said the president’s heart was in health care above all else. "He didn’t run for president to fix derivatives," says Greenberger. "And when he brought in Summers and Geithner, he just thought he was getting the best of the best"—good financial mechanics, in other words, who would "get the car out of the ditch," to use one of Obama’s favorite metaphors.

But the administration had a much bigger job than that. The worst economic downturn since the Great Depression hadn’t occurred just because of a simple crash. An entire era had overreached—the markets-are-always-good, government-is-always-bad zeitgeist that defined the post–Cold War period. The very idea of government regulation and oversight had become heresy during this epoch. Washington policymakers came to ignore the key differences between financial and other markets, differences that economists had known about for hundreds of years. Financial markets were always more imperfect than markets for goods and other services, more prone to manias and panics and susceptible to the pitfalls of imperfect information unequally shared by investors.

Yet that critical distinction was lost in the whirlwind of deregulatory passion that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and other command economies. Finance, completely unleashed, had come to dominate the real economy rather than serve its traditional role as a supplier of capital to goods and services. Venture capital transmogrified into speculative fever. Innovative ways of financing new business ideas evolved into vastly complex derivatives deals, like subprime-mortgage-backed securities, that were often little more than scams.

All of these challenges required a fundamental rethinking of the U.S. and global economy. Yet those who were most aligned with the "progressive" side of the Wall Street reform issue remained, for the most part, on the outside of the administration looking in. Among them were Brooksley Born, the former chairwoman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz. Summers and Geithner, by contrast, had been acolytes of Bob Rubin, the former Clinton Treasury secretary who, along with then–Fed chairman Alan Greenspan, had presided over many of the key deregulatory changes in the ’90s.

And they convinced Obama that the financial system they themselves had done so much to nurture was, on the whole, fine. As long as there were greater capital reserves, leverage limits, and more regulatory oversight, Wall Street could remain intact. (Summers would continue to maintain, well after the crisis, that he had never been a full-blown advocate of deregulation; Geithner did not respond to a request to comment for this article, but previously told me that he was no creature of Wall Street and was simply doing as much as he could to constrain it.)

Obama was clearly not pushing very hard to be FDR or even his trust-busting relative Teddy Roosevelt. Now it looks like grim growth and unemployment numbers could extend all the way into 2012. Distracting himself with health care and other issues, Obama may have politically maneuvered himself out of the only major remedy that could bring unemployment down and growth up enough to assure his re-election: another giant fiscal stimulus. Today, after engendering Tea Party and centrist Democratic resistance to more government spending by pushing his health-care plan, the question is whether he has the political capital he may well need, in the end, to save his presidency. And after a two-year fight over financial reform, one other question still lingers: has Wall Street come out the big winner yet again?

Adapted from Capital Offense, by Michael Hirsh, a new book on the 30-year history behind the financial crash and ongoing economic crisis.

Waiting for Mr. Obama

New York Times Editorial