Ilargi: Malcolm Gladwell writes an article in this week's New Yorker, entitled COCKSURE: Banks, battles, and the psychology of overconfidence. The topic is Wall Street bankers in general, and Bear Stearns' Jimmy Cayne in particular. Gladwell quotes a spring 2008 interview by William Cohan just days prior to Bear's fall, in which Cayne says this, talking about Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner (then head of the New York Fed):

The audacity of that prick in front of the American people announcing he was deciding whether or not a firm of this stature and this whatever was good enough to get a loan. Like he was the determining factor, and it’s like a flea on his back, floating down underneath the Golden Gate Bridge, getting a hard-on, saying, “Raise the bridge.” This guy thinks he’s got a big dick. He’s got nothing, except maybe a boyfriend.

That sets a nice tone. Gladwell continues:

Since the beginning of the financial crisis, there have been two principal explanations for why so many banks made such disastrous decisions. The first is structural. Regulators did not regulate. Institutions failed to function as they should. Rules and guidelines were either inadequate or ignored. The second explanation is that Wall Street was incompetent, that the traders and investors didn’t know enough, that they made extravagant bets without understanding the consequences. But the first wave of postmortems on the crash suggests a third possibility: that the roots of Wall Street’s crisis were not structural or cognitive so much as they were psychological.

Gladwell explains how overconfidence can at times be an asset, but how it also can be lethal. He says Britain lost Gallipoli in 1915 because they knew they were superior, and therefore simply couldn't imagine losing to the Turks.

The British were overconfident at Gallipoli not because Gallipoli didn’t matter but, paradoxically, because it did; it was a high-stakes contest, of daunting complexity, and it is often in those circumstances that overconfidence takes root.

Here's another bit on Jimmy Cayne:

The high-water mark for Bear Stearns was 2003. The dollar was falling. A wave of scandals had just swept through the financial industry. The stock market was in a swoon. But Bear Stearns was an exception. In the first quarter of that year, its earnings jumped fifty-five per cent. Its return on equity was the highest on Wall Street. The firm’s mortgage business was booming. Since Bear Stearns’s founding, in 1923, it had always been a kind of also-ran to its more blue-chip counterparts, like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

But that year Fortune named it the best financial company to work for. “We are hitting on all 99 cylinders," Jimmy Cayne told a reporter for the Times, in the spring of that year, “so you have to ask yourself, What can we do better? And I just can’t decide what that might be." He went on, “Everyone says that when the markets turn around, we will suffer. But let me tell you, we are going to surprise some people this time around. Bear Stearns is a great place to be."

What Malcolm Gladwell means to say is that today's Wall Street leaders have been encouraged by the litany of bail-outs they have received to keep on being as cocksure as Cayne was. The government implicitly says that it won’t let the big financials fail, which provides ample assurance to go out and gamble all the more, not for being more careful.

Goldman Sachs' trading software escapades, combined with their call today for a surge in the S&P 500, which Tyler Durden identifies as just another -albeit cocksure- way to suck the suckers into the market, would seem to make Gladwell's argument a convincing one.

But there's another side to this as well.

President Obama today interestingly made a similar argument. He told PBS television:

"The problem that I've seen, at least, is you don't get a sense that folks on Wall Street feel any remorse for taking all these risks... [..] You don't get a sense that there's been a change of culture and behavior as a consequence of what has happened. And that's why the financial regulatory reform proposals that we put forward are so important.."

Yes, the cocksure culture still exists on Wall Street. But the regulatory reform comes from Obama's economic people, who look no less cocksure, and who also don't seem to have had a change in culture and behavior.

Tomorrow, Neil Barofsky, the special inspector general for the Treasury’s Troubled Asset Relief Program (the SIGTARP office), will report on the Hill that the Treasury should, and easily can, keep much more detailed tabs on where the TARP money has gone and will be going. According to Barofsky the info, which the Treasury has never revealed, is readily available from the banks.

The special inspector general also dropped a huge bombshell by declaring that the total cost of all US bail-out programs may amount to $23.7 trillion. The Chinese, Japanese and Middle East holders of US debt must have been very interested to hear that.

So how does the Treasury Department react to the statements by Barofsky, the man appointed by the President and conformed by the Senate? They act as if he's a complete fool who has no clue what he’s talking about. Which is exactly how Gladwell would have predicted Wall Street CEO's to react, if only because winners know how to bluff.

"Treasury spokesman Andrew Williams said the U.S. has spent less than $2 trillion so far...." "These estimates of potential exposures do not provide a useful framework for evaluating the potential cost of these programs," Williams said. "This estimate includes programs at their hypothetical maximum size, and it was never likely that the programs would be maxed out at the same time."

There are a few options:

- The President and Congress have accidentally appointed absolute nincompoops in Barofsky and Elizabeth Warren, chair of the Congressinal Oversight Panel for TARP.

- Barofsky and Warren are purposely frustrating the good people at the Treasury by incessantly making unfounded claims about false numbers and a lack of transparency.

- The Treasury on purpose gives these people, appointed by the President and with salaries paid by the American people, incomplete and/or faulty information.

- The Treasury thinks it can get away with anything it says and Congress won't dare act on the reports.

- Congress and Treasury both, and in unison, have elected to ignore the watchdogs and think they can get away with anything in front of the American people

We won't have to wait long to find out. Barofsky is on the Hill tomorrow. He will face tough questions, big words and angry senators, but If that’s all there is, you’ll know who's in on the dealmaking.

As for Obama's regulatory reform, forget about it having any positive effect. Wall Street will never reform itself, and the present crew at the Treasury is a Wall Street crew.Their behavior gives them away. They think they can get away with whatever they do.

U.S. Rescue May Reach $23.7 Trillion, Barofsky Says

U.S. taxpayers may be on the hook for as much as $23.7 trillion to bolster the economy and bail out financial companies, said Neil Barofsky, special inspector general for the Treasury’s Troubled Asset Relief Program. The Treasury’s $700 billion bank-investment program represents a fraction of all federal support to resuscitate the U.S. financial system, including $6.8 trillion in aid offered by the Federal Reserve, Barofsky said in a report released today.

"TARP has evolved into a program of unprecedented scope, scale and complexity," Barofsky said in testimony prepared for a hearing tomorrow before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. Treasury spokesman Andrew Williams said the U.S. has spent less than $2 trillion so far and that Barofsky’s estimates are flawed because they don’t take into account assets that back those programs or fees charged to recoup some costs shouldered by taxpayers.

"These estimates of potential exposures do not provide a useful framework for evaluating the potential cost of these programs," Williams said. "This estimate includes programs at their hypothetical maximum size, and it was never likely that the programs would be maxed out at the same time." Barofsky’s estimates include $2.3 trillion in programs offered by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., $7.4 trillion in TARP and other aid from the Treasury and $7.2 trillion in federal money for Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, credit unions, Veterans Affairs and other federal programs.

Williams said the programs include escalating fee structures designed to make them "increasingly unattractive as financial markets normalize." Dependence on these federal programs has begun to decline, as shown by $70 billion in TARP capital investments that has already been repaid, Williams said. Barofsky offered criticism in a separate quarterly report of Treasury’s implementation of TARP, saying the department has "repeatedly failed to adopt recommendations" needed to provide transparency and fulfill the administration’s goal to implement TARP "with the highest degree of accountability." As a result, taxpayers don’t know how TARP recipients are using the money or the value of the investments, he said in the report.

"This administration promised an ‘unprecedented level’ of accountability and oversight, but as this report reveals, they are falling far short of that promise," Representative Darrell Issa of California, the top Republican on the oversight committee, said in a statement. "The American people deserve to know how their tax dollars are being spent." The Treasury has spent $441 billion of TARP funds so far and has allocated $202.1 billion more for other spending, according to Barofsky. In the nine months since Congress authorized TARP, Treasury has created 12 programs involving funds that may reach almost $3 trillion, he said.

Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner should press banks for more information on how they use the more than $200 billion the government has pumped into U.S. financial institutions, Barofsky said in a separate report. The inspector general surveyed 360 banks that have received TARP capital, including Bank of America Corp., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Wells Fargo & Co. The responses, which the inspector general said it didn’t verify independently, showed that 83 percent of banks used TARP money for lending, while 43 percent used funds to add to their capital cushion and 31 percent made new investments. Barofsky said the TARP inspector general’s office has 35 ongoing criminal and civil investigations that include suspected accounting, securities and mortgage fraud; insider trading; and tax investigations related to the abuse of TARP programs.

The Amazing Expanding Bailout

TARP watchdog Neil Barofsky says the total size of the bailout has now hit $23.7 trillion, when all the guarantees are factored in. Of course, the government doesn't just provide a bailout total, so different parties may come up with different numbers. But one thing's clear: ever since the first bailout, the estimate has grown and grown and grown and grown and grown. Let's hope today's number is as big as it gets.

Bailout Overseer Says Banks Misused TARP Funds

Many of the banks that got federal aid to support increased lending have instead used some of the money to make investments, repay debts or buy other banks, according to a new report from the special inspector general overseeing the government's financial rescue program. The report, which will be published Monday, surveyed 360 banks that got money through the end of January and found that 110 had invested at least some of it, that 52 had repaid debts and that 15 had used funds to buy other banks.

Roughly 80 percent of respondents, or 300 banks, also said at least some of the money had supported new lending. The report by special inspector general Neil Barofsky calls on the Treasury Department to require regular, more detailed information from banks about their use of federal aid provided under the Troubled Asset Relief Program. The Treasury has refused to collect such information.

Doing so is "essential to meet Treasury's stated goal of bringing transparency to the TARP program and informing the American people and their representatives in Congress about what is being done with their money," the report said. In a written response, the Treasury again rejected that call. Officials have taken the view that the exact use of the federal aid cannot be tracked because money given to a bank is like water poured into an ocean.

"Although it might be tempting to do so, it is not possible to say that investment of TARP dollars resulted in particular loans, investments or other activities by the recipient," Herbert M. Allison Jr., the assistant Treasury secretary who administers the rescue program, wrote in a letter to Barofsky. The Treasury has required 21 of the nation's largest banks to file public reports each month showing the dollar volume of their new lending.

The government so far has invested more than $200 billion in more than 600 banks under a program that began in October with investments in nine of the largest banks. Some banks have started to repay the aid even as others continue to apply for it. Officials said the program intended to increase the capital reserves of healthy banks, allowing them to make more loans. From the beginning, however, the government invested in troubled banks -- most prominently Citigroup -- that had publicly announced intentions to reduce lending.

The government has also used the money to encourage mergers, such as Bank of America's acquisition of Merrill Lynch and PNC's deal for National City. The report provides the most comprehensive look to date at how banks have used the money, based on voluntary responses to a March survey. Banks were asked to describe how they used the money, but they were not asked to break down the amounts. One response, which the report described as typical, said the money had been used "to make loans to credit worthy customers, and to facilitate resolution of problem assets on our books."

Some bailout firms up lobbying spending in 2Q

Some of the biggest recipients of the government's $700 billion financial bailout, including Bank of America and Morgan Stanley, increased their spending on lobbying in the second quarter as Congress began to look closely at revamping the rule system for financial institutions. Bank of America Corp., which received $45 billion in federal rescue aid, spent $800,000 in the April-June quarter, up from $660,000 in the first quarter. The tally was down from nearly $1.2 million in the year-ago period.

Morgan Stanley's lobbying costs jumped to $830,000 from $540,000 in the first three months of the year, and $690,000 in the second quarter of 2008. "While these companies continue to count their taxpayer cash, they're using their lobbying against critical financial reform," said Ed Mierzwinski, consumer program director at Public Interest Research Group. "Anywhere but Washington, you would think this was the Saturday morning cartoons."

Bailed-out automaker General Motors again was one of the biggest spenders, according to the mandatory disclosure reports filed so far with Congress covering the April-June period. GM spent about $2.8 million on lobbying Congress and the federal government, about the same as in the first quarter but down from $3 million in the second quarter of 2008. GM made an unusually swift exit from bankruptcy protection on July 10, with what once was the world's biggest and most powerful automaker leaner and cleansed of massive debt and burdensome contracts that would have sunk it—if not for $50 billion in federal aid. The government holds a 61-percent controlling interest in the automaker.

Failed insurance conglomerate American International Group Inc., which became an lightning rod for public outrage over its payment of millions in bonuses to employees, trimmed its lobbying spending in the second quarter to $950,000 from nearly $1.3 million in the first quarter and about $2.8 million in the year-earlier quarter. Several of the big banks receiving aid last fall under the Troubled Assets Relief Program have repaid the money in recent weeks.

Ilargi: Read Malcolm Gladwell's COCKSURE: Banks, battles, and the psychology of overconfidence here.

How The Bailout Made The Overconfidence Problem Worse

If Malcolm Gladwell is right—and I think he is—that overconfidence played an important role in creating our financial crisis, it’s time to start asking what we should be doing about this. In the first place, we need to recognize the limits of policy. The search for technical fixes to behavior embedded in the flawed characters of men and women in finance is doomed to failure. We’re not going to find some easy way to discount for overconfidence or even reign it in.

But we can adopt a policy of not making the problem worse. Unfortunately, much of what has gone on in what former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson terms the "rescue" of the financial sector has been making the problem of overconfidence worse. In particular, the various guarantees—implicit and explicit—of assets and liabilities of financial firms tends to increase overconfidence. Everyone from Fed chair Ben Bernanke to Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner has officially announced that the policy of our government is that we will not allow another Lehman Brothers, which means that the government will do whatever it takes to prevent the collapse of a large, complex, systemically important financial institution.

Not many people seem to understand that this policy makes it almost impossible for banks to competently manage their risk. On the surface, the Wall Street banks benefit from lower borrowing costs thanks to the subsidies from both the explicitly guaranteed debt and the broader implicit guarantee against failure. But because this leaves the financial firms without a market check on their activities, it becomes impossible for them to gauge whether they are taking the appropriate risks and the appropriate level of risk.

So, for instance, we see that Goldman Sachs dramatically increased the amount of risk it takes from day to day last quarter. The market doesn’t seem to have penalized them for this additional risk. And why should investors care? They’ve got the government on their side. Which means that Goldman has no market check on its risk, leaving the firm without outside guidance about the wisdom of its investments. In short, the market penalty on overconfidence is destroyed by the guarantees.

Artificially cheap capital also enables Goldman to speculate on trades that would normally be too risky. A kind of phony, government ‘Alpha’ is created by the guarantees—excess gains obtained without internally taking on commensurate levels of risk and its market costs. The folks at Goldman, to pick on them a bit more, are deceived into thinking they are better at this than they are. This is sure to encourage even more overconfidence. Goldman still makes a show about caring about risk management, but the truth is that the firm is basically flying blind. That’s because while traditional risk management isn’t quite useless, but it is nearly so. Even somewhat sophisticated measures such as "Value at Risk" that banks employ don’t really work very well. Goldman itself admits this.

The only real test of risk management is provided by the financial Darwinism of the markets. By reading market signals about products—pricing of assets, pricing of insurance on those prices—banks develop models that can inform them about risk. By reading market signals about their own financial health—their cost of capital, their borrowing cost, the cost to insure their debt, the willingness of customers to enter into trades—risk managers get a view about the risks of their own portfolios and the strength of the business model. Guys and gals whose standard operating procedure is overconfidence, have this trait checked in the markets.

Now we’ve scrambled these signals, and encouraged overconfidence. Shareholders, bondholders, counterparties can become indifferent to risk. Business models can seem more effective than they actually are. In this situation, financial executives cannot appeal to the external market to determine whether they have the right business models, asset portfolios or capital structures. They just have to guessitimate. This calculational chaos is far worse than simple ‘moral hazard.’ It doesn’t matter what regulations are in place, or how closely supervised a firm might be. After all, the regulators and supervisors suffer from the same blindness of the bank executives. The worst kind of overconfidence is encouraged across the broader markets.

It was this calculational chaos that brought down Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Even when closely supervised by regulators and with well-intentioned executives in place, the mortgage agencies were unable to properly evaluate the size of their balance sheets, the content and quality of their portfolios or the appropriateness of their business models. And now we’ve reduced Goldman Sachs to Goldie Mac, another flying blind, overconfident financial firm.

Obama hits out at Wall Street banks

President Barack Obama said on Monday that Wall Street banks had failed to show remorse for the "wild risks" that triggered a financial meltdown and helped to push the United States into recession. Obama unveiled a sweeping regulatory overhaul in June aimed at improving government oversight of banks and markets to avert a repeat of the financial crisis. "The problem that I've seen, at least, is you don't get a sense that folks on Wall Street feel any remorse for taking all these risks," Obama said in an interview with PBS television.

"You don't get a sense that there's been a change of culture and behavior as a consequence of what has happened. And that's why the financial regulatory reform proposals that we put forward are so important," he said. Obama said the planned regulatory reforms would prevent Wall Street firms from taking the "wild risks" they had taken before the financial crisis.

Shareholders should also have the right to weigh in on huge bonuses paid to executives, he said. Wall Street paid more than $18 billion of bonuses in 2008, a year in which it needed trillions of dollars of taxpayer support. Asked if he was concerned about the jump in profits reported by banks Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase & Co, Obama said his administration had less leverage over them now that they had repaid government bailout money.

He said the measures put in his place by his government to stabilize the economy were working, despite unemployment projected to rise above 10 percent within months. "I think we've put out the fire. The analogy I use sometimes is, we had this beautiful house. And there was a fire. We came in and we had to hose it down. "The fire is now out, but what we've discovered is, we need some new tuckpointing, the roof's leaking, the boiler's out, oh, and by the way, we're way behind on our mortgage," he said.

Goldman Ups S&P 500 Target for End-Year

Goldman Sachs raised the S&P 500 index's target for the end of the year to 1060 from 940 Monday, but said the risk of "double-dip" recession remains significant. Goldman Sachs made the move to reflect potential price return of about 13 percent from the current levels, Reuters reported. It also raised the S&P 500 operating earnings view to $52 from $40 for this year. Operating earnings view for next year was also raised to $75 from $63.

Goldman's current economic view is for below-trend growth through 2010, and it believes the risk of a "double-dip" recession is still significant. Asian markets rallied, with the Hang Seng index closing more than 3.7 percent up, while European stock indexes were also up, with banks dominating the upturn. Stock markets in the US and Europe are likely to see a significant rally if indexes manage to rise further from current levels, technical analyst Clem Chambers, CEO of ADVFN, also said Monday.

Is Goldman Starting To Offload Prop Positions?

by Tyler Durden

Abby Joseph Cohen must have threatened with retirement and David Kostin is here to pick up Olympic torch. Goldman Sachs just raised its 2009 year end S&P target to 1060, "13% above the current level" meaning Goldman prop positions are full and the great offloading to marginal buyers has begun. The justification: "After trading in a 10% band for the past three months, our "Pop, Stall, & Sustained recovery" framework, sequential improvement in ex-Financials EPS, stabilization in profit margins, and higher forward EPS guidance all point to a rising market through 2009."

More specifically, 85 Broad is raising its 2009 EPS to $52 from $40, and 2010 EPS to a patently absurd $75 from $63, a 45% increase in bottom line earnings. And just so it seems more credible, "measured on a pre-provision and pre-write-down basis our estimates are $69 and $81. S&P 500 trades at 12.5x our 2010 operating and 11.6x our pre-provision EPS." In other words, pure rose-colored glasses halcyon.

As Q1 and Q2 earnings "beats" have demonstrated, all bottom line upside surprises have come from companies trimming the fat and mass firing employees left and right: alas for the most part revenues have been flat if not materially lower to expectations - just look at GE's recent results for a good recap of what is happening wth the economy theme. Arguably, there is no more SG&A extraction available to the vast majority of US corporations, meaning Goldman is expecting an unprecedented pick up in revenues.

And with the US consumer completely tapped out and unable or unwilling to borrow, this implies that foreign countries will have to pick up the pace in bailing out our top line: so look for much more weakness in the dollar to even remotely justify Goldman's prediction. This will put Bernanke's claim of pursuing a strong dollar policy to the biggest test, as well as Europe's resolve to continue playing in this highly rigged version of F/X "game theory."

But back to Goldman - up until this point the firm has been at least slightly sensitive about catching marginal end buyers. Now the guns are blazing, and as all Wall Street professionals tongue-in-cheekly know all too well, a forceful upgrade is when any firm (Goldman most definitely included) starts to sell into a call (in this case its own). So buyers please beware: you are now implicitly buying the shares that Goldman and other brokers have been accumulating over the past 4 months.

Banks Fail to Make Adequate Loan-Loss Provisions, Moody’s Says

Banks have failed to make adequate provision for the losses on loans and securities they face before the end of next year, Moody’s Investors Service said. U.S. banks may incur about $470 billion of losses and writedowns by the end of 2010, which may cause the banks to be unprofitable in the period, the ratings company said in a report published today. "Large loan losses have yet to be recognized in the banking system," Moody’s said. "We expect to see rising provisioning needs well into 2010."

Banks and financial firms worldwide have reported losses and writedowns of $1.5 trillion since the credit crisis began in 2007, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. New York-based Citigroup Inc. has reported $112 billion of writedowns, more than any other firm, the data show.

Any economic recovery is likely to be "weak and bumpy hook-shaped," Moody’s said. Banks will also be challenged in an environment where government support is replaced by tighter regulation, the report said. Higher credit and funding costs may force a re-pricing of credit, Moody’s added. "The fundamentals of financial institutions are still traveling on a downward slope," Moody’s said. "No-one should consider recent improvements as assurance that the current rebound can be sustained."

Commercial Loans Failing at Rapid Pace

U.S. banks have been charging off soured commercial mortgages at the fastest pace in nearly 20 years, according to an analysis by The Wall Street Journal. At that rate, losses on loans used to finance offices, shopping malls, hotels, apartments and other commercial property could reach about $30 billion by the end of 2009. The losses by regional banks on their commercial real-estate loans will be among the most watched details as thousands of banks report second-quarter results over the next two weeks. Many of the most troubled banks have heavy exposure to commercial real estate. So far, 57 banks have failed this year.

The $30 billion estimate is based on financial reports filed by more than 8,000 banks for the first quarter. The trend continued as a handful of major banks reported second-quarter results, including Goldman Sachs Group Inc., J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp. Regional banks tend to have higher exposure to commercial real estate than these big financial institutions. The commercial real-estate market, valued at about $6.7 trillion, represents 13% of the U.S.'s gross domestic product. But the recession and scarce credit are pushing more commercial developers and investors into default. Meanwhile, property values continue to decline, and banks are required to record a loss on any troubled real-estate loans where the appraised value falls below the amount owed.

Delinquencies on commercial mortgages held by banks more than doubled to about 4.3% in the second quarter from a year earlier, Foresight Analytics estimates. Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D., N.Y.), who heads the House's Joint Economic Committee, said she is working with Treasury Department officials on a plan to try to head off rising defaults on commercial mortgages before they cascade into a crisis. In contrast to home loans, the majority of which were made by about 10 lenders, thousands of U.S. banks, especially regional and community banks, loaded up on commercial-property debt.

Ironically, small banks appear to be much less aggressive in recognizing losses than their bigger brethren. According to the Journal analysis, the largest banks, with assets of more than $100 billion, saw charge-offs roughly quadruple last year, while losses at many medium-size banks grew at a much smaller rate of 120%. One monument to both the excessive froth of the real-estate boom and the morning-after headache setting in for lenders is the landmark Equitable Building, rising 33 stories above downtown Atlanta.

In 2007, San Diego real-estate firm Equastone LLC paid $57 million for the office tower and took out a $51.9 million mortgage from Capmark Bank, a Utah-based unit of Capmark Financial Group Inc. in Horsham, Pa. Equastone planned to expand the tower and attract a tenant with pockets deep enough to rename the building. Shortly after the purchase, the economic slump pushed vacancies higher and rents down. In April, Capmark Bank foreclosed on the building after Equastone defaulted on the debt.

In June, the Equitable Building was sold in a foreclosure auction for $29.5 million, 43% less than the original loan amount. And the buyer? It was 100 Peachtree Street Atlanta, a company formed by Capmark Bank for the purpose of acquiring the building. There were no other bidders. Steven Nielsen, Capmark Bank's chief executive, said the mortgage was written off to the "estimated value" of the building. He wouldn't specify the size of the related charge-off on Capmark's books. Property-tax records show the building was valued at about $44.8 million at foreclosure, which would equal a $7.1 million loss for the bank.

Some bankers say they feel growing pressures from regulators to take losses on commercial real-estate exposure as a way of reducing the possibility of a catastrophic hit later. "We recognize losses as quickly as any bank, partly because bank regulators dictate that," said Ed Garding, chief credit officer at First Interstate Bank, of Billings, Mont. More than 40% of the bank's loans are in commercial real estate, but according to the Journal analysis, annualized charge-offs in 2009 would be just 3% of its nonperforming commercial mortgages as of the end of 2008. That compares with an average of 34% for all U.S. banks.

Mr. Garding said the commercial real-estate market has held up relatively well in First Interstate's markets in Montana and Wyoming. Meanwhile, "we're strongly collateralized so the loan doesn't result in a loss," he added. Among other banks with notably low charge-offs: Based on the Journal study, annualized write-offs this year would be only 9% of all nonperforming commercial mortgages at a Wachovia Corp. unit in Charlotte, N.C. A spokeswoman at Wachovia declined to comment.

At New York Community Bank, a New York State-charted savings bank, that ratio would be a meager 2% in the first quarter. Ilene Angarola, director of investor relations at New York Community Bancorp., the bank holding company, credited the bank's strong underwriting standards. "Even though we have seen a decline in property values, our loan-to-value ratio is conservative enough that we haven't experienced anywhere near the degree of the charge-offs our peers have experienced," Ms. Angarola said.

Some analysts, meanwhile, worry that banks aren't sufficiently recognizing losses on their commercial real-estate loans, thereby exposing themselves to bigger losses later. According to Deutsche Bank AG, since the beginning of last year, the amount of charged-off commercial mortgages as a percentage of such debt outstanding has ranged from a high of 3.2% to as low as 0.3%. "Net charge-offs to date have been highly inadequate," said Richard Parkus, head of commercial mortgage-backed securities research at Deutsche Bank. "This is clearly a problem that is being pushed out into the future." How aggressively regulators respond could help determine how long the commercial-property market remains mired in turmoil. "If banks are allowed to bury problem loans away in their portfolios for years via massive term extensions, this is likely to be a very long process," Mr. Parkus said.

Commercial Real-Estate Prices Fall 7.6% In May

Commercial real-estate prices fell 7.6% in May, according to Moody's Investors Service, as both dollar volume and transaction count reached record lows in the nine-year history of the firm's Commercial Property Price Indices. The indexes are down 29% from a year ago and 35% from their October 2007 peak. The commercial real-estate sector has suffered since mid-2008 as the recession deepened, vacancies increased and new owners have been unable to refinance mortgages. Retail and hotel properties have been hit especially hard in the commercial sector.

"Large commercial real-estate price declines in the last two months suggest that a bottom may be starting to form, although higher transaction volumes would be necessary in order to draw any definite conclusions," Moody's Managing Director Nick Levidy said. Office buildings fared worst, dropping 29% from a year earlier, while industrial buildings were the best performers, down 12%. Apartment buildings in the South suffered a 21% drop, with a 23% slide in Florida, one of the worst-hit states by the housing crisis and global recession.

Ilargi: MyBudget360 is fast becoming a favorite of mine.

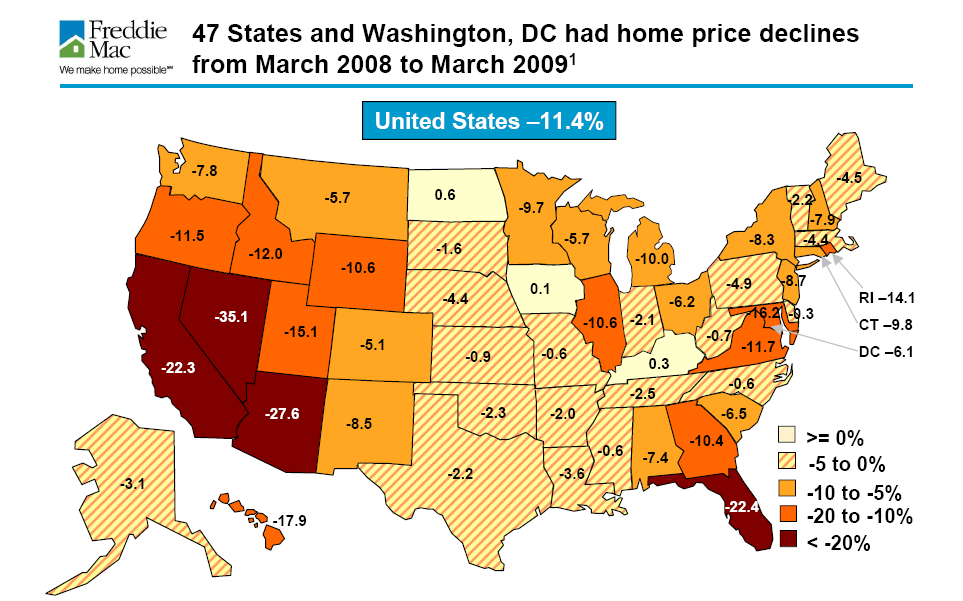

Negative Equity Nation for 1 out of 5 Homeowners: The Psychology of the 10 Million American Homeowners with Zero Equity

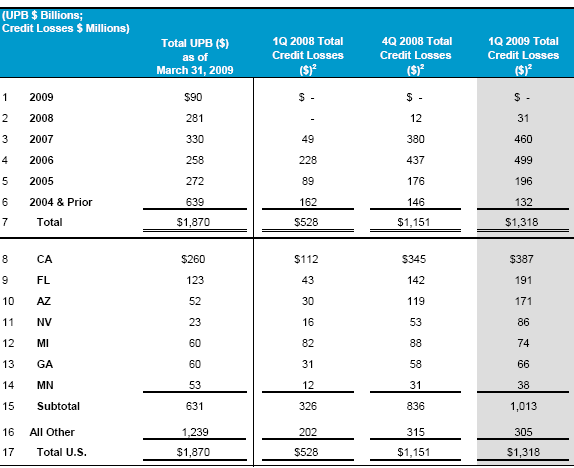

Recent data suggests that the number one factor for walking away from a home is negative equity. For us to understand this dynamic, it is important to understand why someone would leave a home with a mortgage. According to the U.S. Census Bureau some 51.6 million owner occupied homes have a mortgage. This is data from late 2007 so we should be getting the updated data in the ACS that comes out in September of 2009. Another third of homeowners have paid off their mortgage. But with 26,000,000 unemployed and underemployed Americans, paying the mortgage has become more challenging.We recently discussed the rise in bankruptcies which comes even with the stricter guidelines put in place in 2005. A recent Freddie Mac report found that 17 percent of the mortgages in their portfolio had negative equity while another 11 percent had equity of 10 percent or less. Now if you think about it, selling costs can be 6 percent so even those with 10 percent or less equity stand to lose money in a home sale. If we put this together, some 28 percent of Freddie Mac loans if they were sold today may yield the borrower zero or will cost them thousands. This is a recipe for disaster.

First let us take a look at the Freddie Mac world:

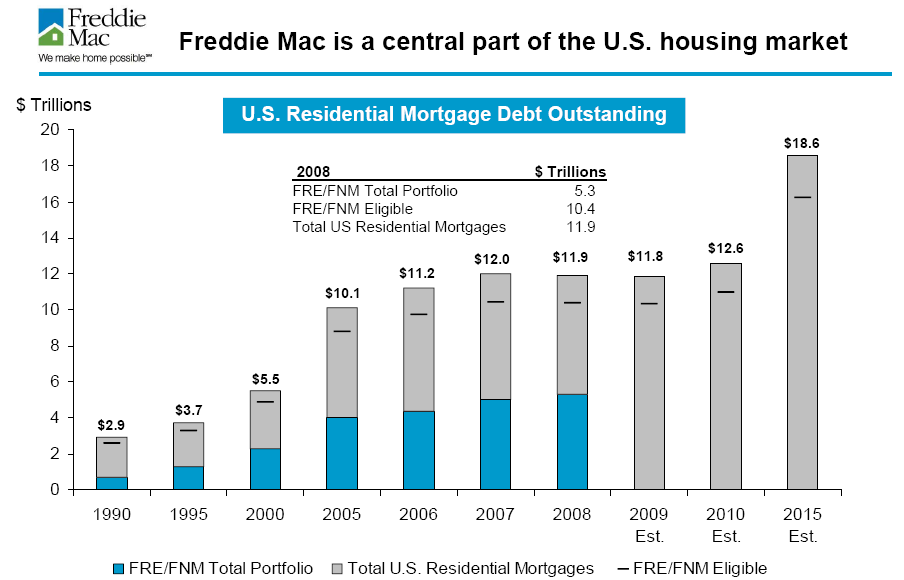

At the end of 2008 some $11.9 trillion in mortgage debt was outstanding. Between Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, a total of $5.3 trillion was in their portfolios. The massive rise in debt followed in line with the multi-decade long housing bubble. Now Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae serve virtually the same role in the mortgage market. They provide so-called liquidity in the secondary arena. What this means is no one else would buy these mortgages now that they know Wall Street virtually turned many loans into casino like instruments. Now, the two giant government agencies are virtually the only game in town. But what is in the report should be of concern. Let us pull out the Freddie Mac data by itself:

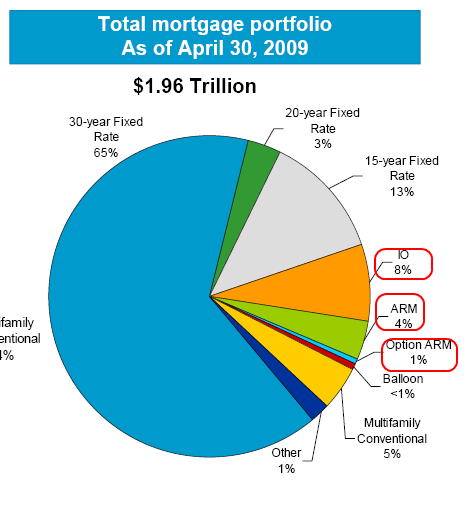

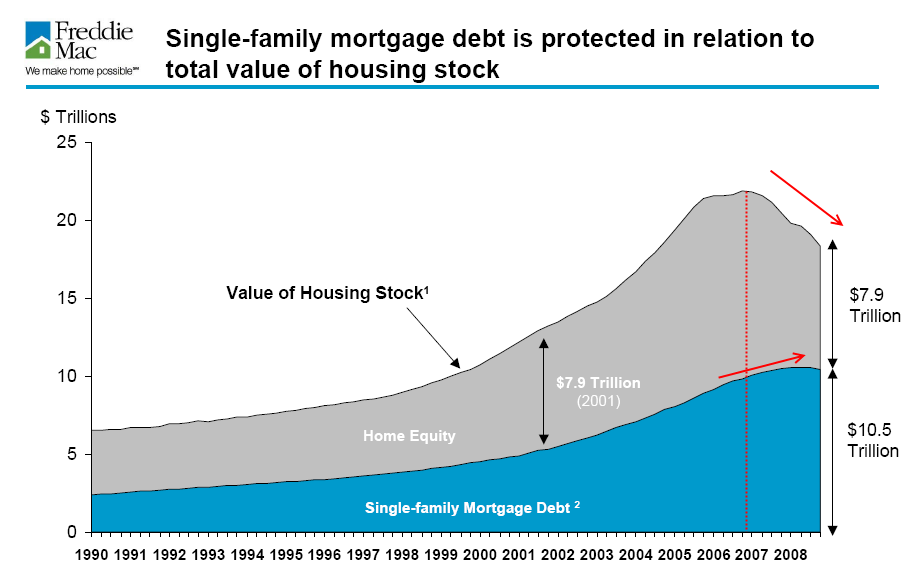

Freddie Mac has a mortgage portfolio worth $1.96 trillion. Of this portfolio 13 percent is made up of option ARMs, ARMs, and interest only products. These are toxic loans. This may not seem like much but this is equivalent to $254 billion in toxic loans. Keep in mind those 30-year fixed mortgage are also seeing rises in defaults. Assuming 17 percent of the borrowers are underwater, some $333 billion in mortgages are severely at risk.Yet the risk is much deeper since the unemployment situation is causing even those with 30-year fixed mortgages to default. The problem with being underwater is that the owner has little motivation to keep paying the mortgage. For most people, they buy homes to live in but also to build up a steady stream of equity. Yet in this decade, we have seen something that hasn’t occurred since the Great Depression. We have seen a nationwide housing market decline. And now, with websites like Zillow and also, local county assessors offices going online many people can check the “value” of their property with very little hassle. So what this creates is an obsessive real estate culture. Let us take a look at what occurred in this decade:

Since the 1980s for nearly 30 years housing prices have been on a tear. Now that the bubble has burst equity levels are now back to 2001. The peak was reached with zany valuation while the debt still exists. That is why on the chart above you’ll notice housing prices declining while mortgage debt levels are still near their peak. It is interesting to note that Freddie Mac assumes booming mortgage debt again:Yet the losses are going to continue mounting as home prices continue to decline. Freddie Mac figures some 1 out of 5 homeowners with mortgages are underwater. Yet we know that there are still many more Alt-A loans that will have much higher default rates. Freddie Mac is probably as conservative of a portfolio as we will get.

Here is some of the data on walking away:

“(WSJ) The researchers found that homeowners start to default once their negative equity passes 10% of the home’s value. After that, they “walk away massively” after decreases of 15%. About 17% of households would default - even if they could pay the mortgage - when the equity shortfall hits 50% of the house’s value, they found.

…

“Our research showed there is a multiplication effect, where the social pressure not to default is weakened when homeowners live in areas of high frequency of foreclosures or know others who defaulted strategically,” Zingales said. “The predisposition to default increases with the number of foreclosures in the same ZIP code.”And here is another point. If you live in area with high defaults the stigma may not be there for a strategic default. Take a look at the rising losses in certain states:

In California the negative equity rate is much higher. So losses are starting to mount and virtually all Alt-A and option ARM holders in the state are underwater. This is going to increase the walking away phenomenon. Even a map of the U.S. will tell us where most of the foreclosures will occur:

With 1 out of 5 homeowners with negative equity, we have a fleet of 10 million Americans being tempted to walk away from their mortgage. With unemployment rising, the default may occur because of necessity. Keep in mind these are people who are still current on their mortgages and not in a stage of default. Unfortunately housing prices still have a way to go on the downside thus pushing more homeowners underwater.

Why Toxic Assets Are So Hard to Clean Up

Despite trillions of dollars of new government programs, one of the original causes of the financial crisis -- the toxic assets on bank balance sheets -- still persists and remains a serious impediment to economic recovery. Why are these toxic assets so difficult to deal with? We believe their sheer complexity is the core problem and that only increased transparency will unleash the market mechanisms needed to clean them up.

The bulk of toxic assets are based on residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), in which thousands of mortgages were gathered into mortgage pools. The returns on these pools were then sliced into a hierarchy of "tranches" that were sold to investors as separate classes of securities. The most senior tranches, rated AAA, received the lowest returns, and then they went down the line to lower ratings and finally to the unrated "equity" tranches at the bottom.

But the process didn't stop there. Some of the tranches from one mortgage pool were combined with tranches from other mortgage pools, resulting in Collateralized Mortgage Obligations (CMO). Other tranches were combined with tranches from completely different types of pools, based on commercial mortgages, auto loans, student loans, credit card receivables, small business loans, and even corporate loans that had been combined into Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLO). The result was a highly heterogeneous mixture of debt securities called Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO). The tranches of the CDOs could then be combined with other CDOs, resulting in CDO2.

Each time these tranches were mixed together with other tranches in a new pool, the securities became more complex. Assume a hypothetical CDO2 held 100 CLOs, each holding 250 corporate loans -- then we would need information on 25,000 underlying loans to determine the value of the security. But assume the CDO2 held 100 CDOs each holding 100 RMBS comprising a mere 2,000 mortgages -- the number now rises to 20 million!

Complexity is not the only problem. Many of the underlying mortgages were highly risky, involving little or no down payments and initial rates so low they could never amortize the loan. About 80% of the $2.5 trillion subprime mortgages made since 2000 went into securitization pools. When the housing bubble burst and house prices started declining, borrowers began to default, the lower tranches were hit with losses, and higher tranches became more risky and declined in value.

To better understand the magnitude of the problem and to find solutions, we examined the details of several CDOs using data obtained from SecondMarket, a firm specializing in illiquid assets. One example is a $1 billion CDO2 created by a large bank in 2005. It had 173 investments in tranches issued by other pools: 130 CDOs, and also 43 CLOs each composed of hundreds of corporate loans. It issued $975 million of four AAA tranches, and three subordinate tranches of $55 million. The AAA tranches were bought by banks and the subordinate tranches mostly by hedge funds.

Two of the 173 investments held by this CDO2 were in tranches from another billion-dollar CDO -- created by another bank earlier in 2005 -- which was composed mainly of 155 MBS tranches and 40 CDOs. Two of these 155 MBS tranches were from a $1 billion RMBS pool created in 2004 by a large investment bank, composed of almost 7,000 mortgage loans (90% subprime). That RMBS issued $865 million of AAA notes, about half of which were purchased by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and the rest by a variety of banks, insurance companies, pension funds and money managers. About 1,800 of the 7,000 mortgages still remain in the pool, with a current delinquency rate of about 20%.

With so much complexity, and uncertainty about future performance, it is not surprising that the securities are difficult to price and that trading dried up. Without market prices, valuation on the books of banks is suspect and counterparties are reluctant to deal with each other. The policy response to this problem has been circuitous. The Federal Reserve originally saw the problem as a lack of liquidity in the banking system, and beginning in late 2007 flooded the market with liquidity through new lending facilities. It had very limited success, as banks were still disinclined to buy or trade such securities or take them as collateral.

Credit spreads remained higher than normal. In September 2008 credit spreads skyrocketed and credit markets froze. By then it was clear that the problem was not liquidity, but rather the insolvency risks of counterparties with large holdings of toxic assets on their books. The federal government then decided to buy the toxic assets. The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) was enacted in October 2008 with $700 billion in funding. But that was not how the TARP funds were used. The Treasury concluded that the valuation problem seemed insurmountable, so it attacked the risk issue by bolstering bank capital, buying preferred stock.

But those toxic assets are still there. The latest disposal scheme is the Public-Private Investment Program (PPIP). The concept is that private asset managers would create investment funds of half private and half Treasury (TARP) capital, which would bid on packages of toxic assets that banks offered for sale. The responsibility for valuation is thus shifted to the private sector. But the pricing difficulty remains and this program too may amount to little.

The fundamental problem has remained untouched: insufficient information to permit estimated prices that both buyers and sellers find credible. Why is the information so hard to obtain? While the original MBS pools were often Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registered public offerings with considerable detail, CDOs were sold in private placements with confidentiality agreements. Moreover, the nature of the securitization process has made it extremely difficult to determine and follow losses and increasing risk from one tranche and pool to another, and to reach the information about the original borrowers that is needed to estimate future cash flows and price.

This account makes it clear why transparency is so important. To deal with the problem, issuers of asset-backed securities should provide extensive detail in a uniform format about the composition of the original pools and their subsequent structure and performance, whether they were sold as SEC-registered offerings or private placements. By creating a centralized database with this information, the pricing process for the toxic assets becomes possible. Making such a database a reality will restart private securitization markets and will do more for the recovery of the economy than yet another redesign of administrative agency structures. If issuers are not forthcoming, then they should be required to file the information publicly with the SEC.

Subprime Brokers Resurface as Dubious Loan Fixers

From the ninth floor of a downtown office building on Wilshire Boulevard, Jack Soussana delivered staggering numbers of mortgages to homeowners during the real estate boom, amassing a fortune. By Mr. Soussana’s own account, his customers fared less happily. He specialized in the exotic mortgages that have proved most prone to sliding into foreclosure, leaving many now scrambling to save their homes.

Yet the dangers assailing Mr. Soussana’s clients have yielded fresh business for him: Late last year, he and his team — ensconced in the same office where they used to broker mortgages — began working for a loan modification company. For fees reaching $3,495, with most of the money collected upfront, they promised to negotiate with lenders to lower payments on the now-delinquent mortgages they and their counterparts had sprinkled liberally across Southern California.

"We just changed the script and changed the product we were selling," said Mr. Soussana, who ran the Los Angeles sales office of Federal Loan Modification Law Center. The new script: You got a raw deal, and "Now, we’re able to help you out because we understand your lender." Mr. Soussana’s partners at FedMod, as the company is known, were also products of the formerly lucrative world of high-risk lending. The managing partner, Nabile Anz, known as Bill, previously co-owned Mortgage Link, a California subprime lender, now defunct, that once sold $30 million worth of loans a month.

Jeffrey Broughton, one of FedMod’s initial partners, served as director of business development at Pacific First Mortgage, a lender that extended so-called Alt-A mortgages for borrowers with tarnished credit for Countrywide Financial, which lost billions of dollars on bad mortgages before being rescued in an acquisition. FedMod is but one example of how many of the same people who dispensed risky mortgages during the real estate bubble have reconstituted themselves into a new industry focused on selling loan modifications.

Despite making promises of relief to homeowners desperate to keep their homes, FedMod and other profit making loan modification firms often fail to deliver, according to a New York Times investigation based on interviews with scores of former employees and customers, more than 650 complaints filed with the Better Business Bureau, and documents filed by the Federal Trade Commission in a lawsuit against the company.

The suit, filed in California federal court, asserts that FedMod frequently exaggerated its rates of success, advised clients to stop making their mortgage payments, did little or nothing to modify loans and failed to promptly refund fees. The suit seeks an end to FedMod’s practices, and compensation for customers. "Our job was to get the money in and then we’re done," said Paul Pejman, a former sales agent who worked out of FedMod’s two-story headquarters in Irvine, Calif. He recounted his experience, he said, because "I really feel bad."

"I had people calling me crying, and we were telling them, ‘You can pay me or you can lose your house,’ " Mr. Pejman said. "People were giving me every dime they had, opening credit cards. But I never saw one client come out of it with a successful loan modification." Mr. Anz, who is challenging the F.T.C. lawsuit, acknowledged that FedMod’s business went "horribly wrong," but he maintains the company made genuine efforts to help delinquent borrowers. He said FedMod has refunded fees to 3,000 dissatisfied customers, while modifying 1,500 mortgages.

FedMod is among dozens of similar companies that have been accused by state and federal authorities of fraudulent business practices. On the same day in April that the F.T.C. sued FedMod, it brought action against four similar companies and sent letters of warning to 71 others. Last week, the commission brought lawsuits against four more loan modification companies, advancing an enforcement campaign involving 23 states.

Many of the companies formerly operated as mortgage brokers, The Times found. Since October, the California Department of Real Estate has ordered 210 businesses and individuals to stop offering loan modification or foreclosure prevention services, because they lacked a real estate license, as required by the state. In fact, nearly half the people have roots in the mortgage industry or other areas of real estate, according to public records.

Debt Barter Inc. is among them. A loan modification company based in Irvine that was cited by the state in January for collecting upfront fees without a license, it is owned by Sean R. Roberts, who formerly headed Instafi, a mortgage broker that closed $2 billion worth of loans a year at its peak. Since February, customers have filed 17 complaints against Debt Barter with the Better Business Bureau. Most accused the company of charging upfront fees, then failing to lower their payments. "We can’t please everyone all the time," said Mr. Roberts, who added that the company had modified loans for nearly 300 of its roughly 500 clients.

In Aliso Viejo, Calif., the Citywide Mortgage Corporation, which previously brokered Alt-A and subprime loans, last year became a loan modification company, USMAC. The company has not received a cease and desist order, but complaints on numerous consumer Web sites assert that it fails to deliver. "I’m saving homes," said the company’s president, Scott Gimbel, who claimed a success rate above 70 percent.

Chris Mozilo, nephew of Angelo R. Mozilo, the former chief executive of Countrywide Financial — a name synonymous with the subprime disaster — recently started a new business, eModifyMyLoan. It sells software that homeowners can use to apply for loan modifications. Chris Mozilo worked at Countrywide for 16 years. "I’m very proud of my career in mortgage lending," he said. "We helped millions of people achieve the goal of homeownership."

From its inception in the middle of 2008, FedMod aimed to dominate the loan modification industry, growing swiftly with the aid of a national advertising campaign. Mr. Broughton, 49, had worked in the mortgage industry since the mid-1980s. As the market ground to a halt in 2008, he founded FedMod with two Los Angeles entrepreneurs, Steven Oscherowitz and Boaz Minitzer. Mr. Broughton sought to distinguish his company from the unscrupulous ventures that dominate the industry. "You had a lot of these modification companies that were subprime guys," he said. "All they cared about was making quick dollars."

But the partners behind FedMod had their own questionable backgrounds. In the mid-1990s, Mr. Oscherowitz settled an F.T.C. lawsuit that accused his company, Universal Merchants, of falsely marketing the weight-loss benefits of a dietary supplement. The partners entrusted Mr. Soussana with FedMod’s Los Angeles sales office precisely because he had proved adept at selling the sorts of loans that now required modification. In 2006, Mr. Soussana, then 30, was listed as the nation’s sixth most prolific mortgage broker by Mortgage Originator, a trade magazine, brokering $318 million worth of loans. The same year, he paid $1.8 million for a house near Beverly Hills.

"He was one of the biggest guys in subprime mortgages," Mr. Minitzer said. "He basically wanted to get back to his old days of 50, 60, 70 guys in his office, and we could help because we were basically taking over the market." The three original partners brought in Mr. Anz to gain a crucial asset: his law license. Having a lawyer in charge enabled them to market their venture as a law firm and thus collect upfront payments under California rules. "Jeff asked me how I could, for lack of a better word, legitimize it," Mr. Anz said.

The California Department of Real Estate warns consumers that many dubious loan modification companies have organized themselves as law firms solely to allow them to collect upfront fees, even though the lawyers have little, if anything, to do with the services provided. The department cautions consumers against hiring such companies. In its lawsuit against FedMod, the F.T.C. contends that the company’s advertisements implied it had the backing of the federal government. "If you’re like the millions of Americans out there who are struggling to pay a mortgage, you may be eligible for the Federal Loan Modification Program," radio ads beckoned.

Aggressive marketing ensured that Mr. Pejman, 22, never lacked for calls when he started at the Irvine sales office in January. He had worked at three wholesale mortgage brokerages. Now, a trainer emphasized he was at a law center. "Our big sales pitch was that an attorney could do a better job with your loan modification," Mr. Pejman said. "If you told them these were basically washed-up people from the mortgage industry, or just people sending in paperwork, they would say, ‘Well, why bother? I might as well do this myself.’ " He went on: "It was misleading to the client. Attorneys never touched those files."

Among the 700-plus full-time employees who worked for FedMod this spring, only nine were lawyers, Mr. Anz said, though the company retained a lawyer in every state. Mr. Pejman and his fellow agents urged homeowners to send FedMod $3,495; the agents were promised a 30 percent commission for fees they took in. Most clients could not come up with more than $1,000 and agreed to a payment schedule for the rest. Assurances of relief from a homeowner’s loan terms were typically extravagant, Mr. Pejman said.

"A big grabber was that your loan will be reduced to 2.5 percent to 5 percent on a 30-year fixed rate loan," he said. "They’d print out all these mythical success stories for us to read over the phone."

Under FedMod’s policies, agents were prohibited from making false claims, counseling clients not to pay their mortgages or providing success rates, Mr. Anz said. New clients received follow-up compliance calls to ensure they understood nothing was guaranteed. But sales agents were told of such policies with a wink, Mr. Pejman said.

"They basically told us, ‘Do whatever you need to do,’ " he said. " ‘It’s a sales floor. You’re here to sell.’ People would quote success rates and just pull them out of thin air. People would say 60 percent, 80 percent, 90 percent. To the average Joe in Kansas, that sounded great. But the reality is that 50 percent were immediately declined by the lender." What shocked Mr. Pejman was how readily customers handed over their credit card numbers. Sales agents tapped into a deep vein of anxiety. "I’d hear people say, ‘Would you pay $1,000 to save your home? To save your marriage? Your kids’ education?’ " he recalled. "I’d hear people say, ‘Yeah, we’re the federal government.’ There were a lot of corrupt people working there."

In Charlotte, N.C., Joshua Garland telephoned FedMod in March after seeing one of its television commercials. Mr. Garland’s wife had been laid off from her hospital job. He had lost his job as a chef and was now bartending. Their monthly income had plunged from $3,200 to less than $1,000. They were already three months behind on their mortgage. A FedMod agent confidently described how his company could cut their monthly payments from $1,200 to $532, Mr. Garland recalled. But first, he had to pay a $995 "retainer fee." This was nearly as much as Mr. Garland earned in two weeks. Dental bills were piling up for his three children. He was behind on his utilities.

"I told him, ‘We have $1,200 left to make our mortgage payment, and if we give that money to you, we’re going to get further behind,’ " Mr. Garland recalled. "He said, ‘Go ahead and make the $995 payment, because once you’re under our plan, the bank can’t foreclose on you.’ " After several follow-up calls from the agent, Mr. Garland paid. Then, months passed with no contact from FedMod, he said. He left countless messages seeking updates, demanding a refund. His lender foreclosed on his house, scheduling a sale for Aug. 26.

"This guy hounds me for the $1,000, and then as soon as I pay him he disappears," Mr. Garland said. "I usually don’t fall for stuff like this. I can usually tell if it’s a scam. But this guy, I mean he came with his guns loaded." FedMod was drowning in cases. The pipeline swelled by 8,000 clients from December to March, according to Mr. Anz. Once sales agents took in applications, they passed files on to the processing department, where case managers were supposed to assemble documents and submit them to lenders. But their offices were hopelessly underequipped.

"The owners didn’t want to invest in software, so everything was tracked manually," said Rachelle Cochems, who took over as operations manager on Jan. 19 and left the company in May after FedMod stopped paying her. "We couldn’t handle the volume we were taking in. The system was broken." Each case manager was responsible for as many as 200 files at a time, Ms. Cochems said, making it impossible to keep in regular touch with customers. Some files floated in limbo, because sales agent did not bother handing them over.

"You’re paying the sales agent upfront," Ms. Cochems said. "So what motivation does he have to get it closed?" In February, Mr. Anz shut the Los Angeles sales office, uncomfortable with reports that Mr. Soussana had filled it with "unsavory types" from the mortgage industry, he said. "I’m not a shady person," Mr. Soussana said. By March, sales agents were inundated by calls from furious clients who had paid long ago, but not heard from anyone. Some called from motels, their belongings piled in boxes, weeping as they recounted losing their homes.

The agents let most calls go to voicemail, playing the most dramatic messages over speakerphones for communal amusement, Mr. Pejman said. "Guys would sit there and laugh," he said. " ‘This lady’s going crazy,’ that sort of thing." The next month, Mr. Anz took full control of the company, banishing his partners and blaming them for "a train wreck." He ceased marketing, he said, and concentrated on processing the backlog of files.

In April, the F.T.C. filed its lawsuit, prompting credit card companies to freeze their accounts with FedMod. The court imposed a temporary restraining order, barring FedMod from acquiring new customers. By the time Rana Hajjar began working there on April 13 as a client representative, she found the company utterly chaotic. "They just handed me 70 files and told me to call these people because they’re very upset," Ms. Hajjar recalled. "The majority of them had paid three or four months earlier and had never heard from anyone. I was yelled at from today until tomorrow."

Several times a week, clients called to report that the police were at their door, ordering them out for foreclosure sales, Ms. Hajjar said. When she alerted negotiators, they sometimes called banks and postponed sales, but usually they ignored her messages, she said. When Ms. Hajjar cashed her first paycheck, it bounced, she said. Over the next three weeks, she never received payment. On Monday, May 11, her manager told her and dozens of other employees to take the rest of the week off because the company had no money for payroll.

She was never called back, later adding her name to a file of more than 120 wage disputes leveled against FedMod with the California Labor Commissioner. Today, FedMod has only 40 employees, said Mr. Anz, pledging to plow through the company’s 4,200 remaining files. "We’re doing what we can," he said. "I’m the bad boy of loan mods." Yet as television advertisements attest, many other companies remain aggressive in what amounts to perhaps the last growth industry left in American real estate.

What's Wrong With Spending Stimulus Cash On Mozzarella Cheese?

As only he can do, Matt Drudge set off a mini scandal today, pointing to some questionable stimulus expenditures, like $1.5 million for mozzarella cheese and $16.8 million for canned pork. Drudge's little hyperlinks made such big waves this morning, that the Agriculture Secretary put out a press release explaining what the money went to. Anyone who pays even the slightest attention to government spending and stimulus efforts won't be particularly surprised by any of this, and the money isn't even that much.

Plus, as liberal political pundit Peter Feld points out, the point is just to get cash "into the economy," and it doesn't matter how it gets there. Unfortunately, this is flat-out wrong, and it exposes a deep flaw in the orthodox Keynesian idea that the job of the government is to just get "demand" higher when it goes into a lull. Fostering a healthy economy is not about stuffing it up with cash like a Christmas turkey, or just getting people to buy "stuff." It's about facilitating actually productive trade.

So for example, we doubt that Feld would think it'd be a good idea to spend money on shoddy houses in the middle of California's inland empire, even though technically this would constitute getting money into the economy. And we think many would agree that we don't need new, gigantic highway projects stretching deep into the exurbs, and that rail projects would be better. Both would get money into the economy, but one might be good for the economy, and the other might keep us mired deep in the weeds. The stuff we spend our money on actually matters.

Remember, it's easy enough to get cash into people's hands. You can just print it, or repeal the payroll tax or extend unemployment benefits or whatever you want. If only cash=wealth, it'd be super simple. But the actual challenge is in making sure you have a scenario in which people can create real wealth for themselves, and you're not going to get there if you insist that "demand" is this big pile of gloop (or mozzarella cheese) that you sometimes just need to make more of.

Financial Invention vs. Consumer Protection

by Robert J. Shiller

James Watt, who invented the first practical steam engine in 1765, worried that high-pressure steam could lead to major explosions. So he avoided high pressure and ended up with an inefficient engine. It wasn’t until 1799 that Richard Trevithick, who apprenticed with an associate of Watt, created a high-pressure engine that opened a new age of steam-powered factories, railways and ships.

That is how innovation often proceeds — by learning from errors and hazards and gradually conquering problems through devices of increasing complexity and sophistication. Our financial system has essentially exploded, with financial innovations like collateralized debt obligations, credit default swaps and subprime mortgages giving rise in the past few years to abuses that culminated in disasters in many sectors of the economy.

We need to invent our way out of these hazards, and, eventually, we will. That invention will proceed mostly in the private sector. Yet government must play a role, because civil society demands that people’s lives and welfare be respected and protected from overzealous innovators who might disregard public safety and take improper advantage of nascent technology. The Obama administration has proposed a number of new regulations and agencies, notably including a Consumer Financial Protection Agency, which would be charged with safeguarding consumers against things like abusive mortgage, auto loan or credit card contracts.

The new agency is to encourage "plain vanilla" products that are simpler and easier to understand. But representatives of the financial services industry have criticized the proposal as a threat to innovations that could improve consumers’ welfare. As the story of the steam engine shows, innovation often entails tension between safety and power. We need to foster inventions that better human welfare while incorporating safety mechanisms that protect the public. Could the proposed agency accomplish this task?

The subprime mortgage is an example of a recent invention that offered benefits and risks. These mortgages permitted people with bad credit histories to buy homes, without relying on guaranties from government agencies like the Federal Housing Administration. Compared with conventional mortgages, the subprime variety typically involved higher interest rates and stiff prepayment penalties. To many critics, these features were proof of evil intent among lenders. But the higher rates compensated lenders for higher default rates. And the prepayment penalties made sure that people whose credit improved couldn’t just refinance somewhere else at a lower rate, thus leaving the lenders stuck with the rest, including those whose credit had worsened.

This made basic sense as financial engineering — an unsentimental effort to work around risks, selection biases, moral hazards and human foibles that could lead to disaster. This might have represented financial progress if it weren’t for some problems that the designers evidently didn’t anticipate. As subprime mortgages were introduced, a housing bubble developed. This was fed in part by demand from new, subprime borrowers who now could enter the housing market. The bursting of the bubble had results that are now all too familiar — and taxpayers, among others, are still paying for it all.

This raises a question: If a consumer agency had been set up 20 years ago, would the subprime mortgage crisis have been prevented? We don’t know, but it seems improbable.

Such an agency would most likely have slowed some abusive practices, like offering low teaser rates on adjustable-rate mortgages and hiding information about future rate increases in fine print that most people do not read. That kind of regulatory intervention would have reduced the severity of the crisis, and that is no small thing. On the other hand, unless these regulators were extremely vanilla in approach and just said no to any innovation, or unless they had an unusually deep understanding of speculative bubbles, I think they would have allowed most of those subprime mortgages.

And they probably wouldn’t have had the detailed knowledge they would have needed to halt the decline of lending standards on prime mortgages in a timely way. In all likelihood, we would still be in this financial crisis.

In short, the new agency seems a good idea, and, if it is created, it should be chartered to support innovation and should be staffed by people who know finance and its intricacies, including some who appreciate that human behavior must be understood and factored into financial design. But that leaves us with the deeper quandary: Our society needs financial innovation, and still seems vulnerable to changing animal spirits and speculative bubbles that create truly big problems. Even if they can be mitigated, periodic crises may not be preventable, at least not by banning abusive credit cards or even by throwing the bad guys in jail.

We need consumer products that people can use properly, and if this is what "plain vanilla" means, that’s a good thing. But we also need financial innovation that responds to central problems. The effectiveness of our free enterprise system depends on allowing business people to manage the myriad risks — including the risk of asset bubbles — that impinge on their operations in the long term. And this process needs constant change and improvement.

Complexity is not in itself a bad thing. It is, in fact, a hallmark of modern civilization. A laptop computer is an immensely complex instrument, with trillions of electronic components, and almost none of us can explain what goes on inside it. Yet it can be designed well so that it seems plain vanilla to the ultimate user. And as for steam engines, the modern turbine high-pressure versions are not plain vanilla in any sense. They are sophisticated triumphs of engineering. They help generate most of our electric power with very few accidents.

Shiller tries to defend subprime mortgages

by Felix Salmon

Robert Shiller thinks that creating a Consumer Financial Protection Agency "seems a good idea", but is also a fan of financial innovation:Our financial system has essentially exploded, with financial innovations like collateralized debt obligations, credit default swaps and subprime mortgages giving rise in the past few years to abuses that culminated in disasters in many sectors of the economy. We need to invent our way out of these hazards…

The subprime mortgage is an example of a recent invention that offered benefits and risks… the higher rates compensated lenders for higher default rates. And the prepayment penalties made sure that people whose credit improved couldn’t just refinance somewhere else at a lower rate, thus leaving the lenders stuck with the rest, including those whose credit had worsened.

We need consumer products that people can use properly, and if this is what "plain vanilla" means, that’s a good thing. But we also need financial innovation.

This is the point at which I want to do my Jon-Stewart-rubbing-his-eyes act: Shiller really has just written a column defending "financial innovation" and using, as his sole example of a good financial innovation, the subprime mortgage. Shiller seems to think that the best response to harmful financial innovations like CDOs is even more financial innovation, to reverse the damage initially caused. Wouldn’t it be better just to scale back the amount of financial innovation we had in the first place? Net-net, financial innovation is a bad thing: the downside, during times of crisis, is higher than the upside in more normal years.

And Shiller’s defense of subprime mortgages is unbelievably weak. He never comes close to addressing the point that a huge proportion of subprime mortgages were sold to people who could have qualified for a prime mortgage; and his attempted defense of prepayment penalties is utterly bonkers. People prepaid subprime mortgages for three main reasons: (a) because their house had gone up in value and they wanted to do a cash-out refinance; (b) because they were selling their house; and (c) because interest rates had fallen since they took out their mortgage. The number of people who wanted to prepay a subprime mortgage because their credit had improved was negligible.

In fact, as Shiller knows but won’t admit, prepayment penalties were a profit center for subprime lenders — a way of squeezing money out of borrowers at the end of the relationship as well as at the beginning. If this is financial innovation, I want much less of it, thanks for asking. And while I agree that the CFPA "should be staffed by people who know finance and its intricacies". I just don’t think they should start from the assumption that financial innovation is a good thing.

Geithner Has Tough Task In Marketing US Debt

Timothy Geithner, architect of bank, auto and economic rescue plans, has another high-stakes job these days: traveling bond salesman. The recession, financial crisis and two wars have pushed the federal deficit above $1 trillion, a record level that makes the Treasury secretary's role as chief marketer of U.S. debt tougher than any of his recent predecessors'. Geithner, who traveled last week to the Middle East and Europe, has to convince foreign investors to keep buying Treasury bills, notes and bonds; they hold nearly half of the government's roughly $7 trillion in publicly traded debt.

"He's a smart guy but it's a very, very big task," said Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a left-leaning Washington think tank. If foreign demand for U.S. debt sags, that could drive up interest rates and spell big trouble for an economy hobbled by 9.5 percent unemployment. Higher rates would make it more expensive for consumers to buy homes and cars, and for businesses to finance their operations. In the worst case scenario, a rush by foreigners to sell their U.S. debt could send the dollar crashing and inflation soaring. Because that would also hurt the value of their remaining holdings and the U.S. economy – a key market for their exports – private analysts believe such a scenario is not likely to occur.

With the risks in mind, Geithner last week visited Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, whose vast oil wealth gets recycled into Treasury holdings. Last month, he visited China, the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasuries. That trip was marked by an extra dose of drama. In March, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao said his country was concerned about the "safety" of the large amounts of money it had lent to the United States. Throughout these trips, Geithner very much stuck to his sales script, at least in his public pronouncements. He said the Obama administration was committed to guarding the value of the dollar and, once the economy improves, shrinking the deficit.

The deficit has been driven higher in part by the $787 billion economic stimulus package and $700 billion financial system bailout approved by Congress over the past year. The deficit-cutting proposals the administration has so far revealed would fall far short of what is needed. "If the Obama administration has a credible plan to bring the deficits down, they are keeping it a deep secret at the moment," said Michael Mussa, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute and former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund.

With nearly three months left in the budget year, the Obama administration forecasts that this year's deficit will total $1.84 trillion, more than four times the size of last year's record tally. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates the annual deficits under the administration's spending plans will never drop below $633 billion over the next decade. And it forecasts an additional $9.1 trillion added to the debt held by the public – the amount that Geithner has to finance with bond sales.

During a stopover in Paris on Thursday, Geithner acknowledged in an online chat sponsored by the French newspaper Les Echos that "the dollar's role in the international financial system places special responsibilities on the United States." The foreigners Geithner meets with have a keen sense of the pressure he faces. When Geithner told a packed auditorium at Peking University that Chinese investments in the U.S. were safe, his comment was greeted by laughter. The students appeared to be laughing more at the quickness with which Geithner had responded to a question, not at what he said. Still, the reaction did highlight underlying skepticism.

Officials in the Middle East last week gave no public hint of nervousness. UAE crown prince Sheik Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, who met with Geithner last Wednesday, stressed the strength of his country's relationship with the U.S. in comments carried by state news agency WAM. "The UAE attaches great significance to further promoting cooperation with the friendly United States in all areas, and in banking, finance, trade, investment and education in particular," Sheik Mohammed said.